This week’s episode is “The Daggers Come Out.”

The Council of Nicaea dealt with more than just the Arian controversy over how to understand the nature of Christ. The 300 bishops who gathered in Nicaea also issued a score of rulings on issues of church life that had been subjects of discussion for years. Chief among these was setting the date for the annual celebration of the resurrection of Christ. They also set various rules for organizing the Church & the ministry of deacons and priests.

As the Church grew with more congregations being formed, the need for some organization became apparent. So for administrative purposes, the church-world was divided into provinces with centers at Rome in the West & in the East, four headquarters; Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem & Constantinople. It may seem odd to us today that only 1 church was the Western center while the East had 4. Why so many? The answer is that it was in the E the Church had its greatest extent & growth.

The bishops at these 5 churches were given oversight of their surrounding regions. This stoked a major rivalry between Alexandria & Antioch, the Empire’s 2nd & 3rd largest cities after Rome. These 2 cities vied with each other for leadership of the entire East. That rivalry became more complex when the church at Constantinople, the new eastern capital of the Empire, was added to the mix. The contest between them at first took place mostly in the realm of theological debates but later became sinister when ecclesiastical position equaled power and wealth.

But, the amazing unanimity of the bishops at the Council of Nicaea seemed to presage the dawn of an era of peace and tranquility for the Church and Empire. It was not to be. While the bishops agreed on the word “homo-ousias” to describe Jesus being one substance with the Father, many bishops, possibly even most, left Nicaea feeling the Emperor Constantine’s pressure coerced them into taking a position they weren’t happy with. After Nicea, many of them regretted knuckling under & grew resentful of his pressure to settle the issue.

I don’t want to get too technical here, but that’s precisely what this all was; a highly technical issue of the parsing of words, trying to find an accurate expression of their belief about the humanity and deity of Christ. It isn’t that the bishops didn’t believe Jesus was anything less than God. It’s just that the word used in the Nicene Creed, ‘homo-ousias,’ didn’t capture what they thought the truth of Jesus deity was. Many of the bishops were uncomfortable with that word because the Gnostics had used it to describe their beliefs about Jesus a few decades before.

So not long after the Nicean Council, many of those who’d signed the Creed backed away from it. Several alternate creeds were offered, some close to the Nicene version and others at great distance from it. None of them repeated the word ‘homo-ousias.’

It was in the East that the greatest theological turmoil ensued. After Constantine, several of the Emperors were decidedly hostile to the Nicene position. A few were openly friendly with the Arianism Nicaea was supposed to have buried.

As we saw last time, though Alexandria was a lead church in the East, its Bishop Athanasius was the sole standard-bearer for the Nicene Creed in the East. Though Constantine had sponsored and endorsed Nicaea and enforced its terms by the use of civil authority, his desire to bring unity to the Empire and Church moved him to press bishops to re-install Arius and his followers; not as leaders, but simply as church members. When Athanasius and other Nicene-keeping bishops refused, Constantine punished them with banishment. Then, after a season, he changed his mind and allowed them to return. But when those same church leaders again proved too principled for Constantine’s taste in some other ruling he wanted adopted, he’d banished them once again. Constantine’s successors followed his lead.

For reasons relating more to politics than doctrinal concerns, the half-century after the Council of Nicaea, saw the Eastern church effectively taken over by Arians. The Pro-Arian Bishop of Nicomedia, Eusebius (not the famous church historian) was allowed to return to his post after a 2-year exile. He immediately set about to undo Nicea. He persuaded Constantine to reverse Arius’ exile and when the heretic appeared before the Emperor, he confessed a statement of faith that appeared to line up with the orthodoxy of Nicaea, but was in fact only a clever piece of verbal gymnastics that fooled the Emperor. Athanasius wasn’t fooled and refused to affirm Arius as a member in good standing. So Eusebius and his supporters plotted to get rid of him. A council of Eastern bishops was called in 335 at Tyre as they were on their way to Jerusalem to celebrate the dedication of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher Constantine had just had built. At Tyre, the bishops condemned Athanasius as guilty of conduct unbecoming a Bishop. Which is tragically comical, because Athanasius was about as pious as one could get. What Eusebius and his cronies meant was that a bishop ought to agree with them, “because well, just because. Stop being contentious or we’ll charge you with conduct unbecoming a bishop!” Athanasius recognized the ambush and went to the Emperor to plead his case. Eusebius followed and warned Constantine he’d heard Athanasius had threatened to call a strike of the Alexandrian dock-workers who loaded grain into the barges that fed both Constantinople and Rome. Without Egypt’s harvest, the cities would go hungry & vicious riots would ensue. Eusebius’s charge was ridiculous but he knew the Emperor couldn’t risk it being true. Constantine was forced to banish Athanasius to Trier (TREE-yer) in Germania.

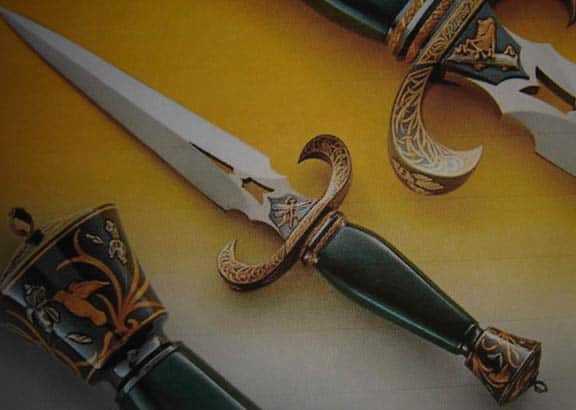

If you’re a subscriber to CS, you know we sometimes breeze over years, even decades of church history with only a brief summary. Other times we slow down & go in depth. The reason for this is because there are moments, seasons, even eras when events occur, trends develop, movements are birthed that have a major impact on the course of following years. We’ve slowed down to focus on the post-Nicaean years because they’re illustrative of how ruinous the infiltration of political power has been to the Church. Only 20 years passed after Constantine’s conversion and the Edict of Milan, and already church leaders are using their authority, not as spiritual guides to bless those God entrusted to their charge but to accumulate more power & influence in the political & civil realm. A man like Athanasius, whose sole concern was to glorify God & faithfully discharge his role as a pastor, proved no match for a conniving political operator like Eusebius who used his office as Bishop to bend the Emperor’s ear & secure civil authority to enforce his will. While the once-persecuted Church rejoiced that the Emperor was finally one of them, they couldn’t foresee that his merging of church and state would bring about a whole new set of problems that would turn their leaders into power-hungry competitors. While many bishops resisted the lure of political power & stayed true to their spiritual task, many others were seduced and plunged into the great game of ecclesiastical politics. The machinations of the contest between Eusebius & Athanasius would likely not have occurred during the persecutions of the previous decades. But when civil authority was lent church leaders, the doctrinal daggers came out and theology became a ruse behind which to plot how to gain political advantage.

The historian Eusebius, not the villain who attacked Athanasius, but the one who wrote the first Church History chronicle, helped blur the lines between church and state. After charting the church’s course from the Apostles to Constantine in his book Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius presented Constantine as much more than just a ruler kindly disposed toward the Faith. Oh no – Eusebius sketched Constantine as much more than that. He was God’s agent; ordained by God to provide leadership for both the Church & Empire.

Eusebius said that just as the Church was a manifestation of the Kingdom of God on Earth, set to rule in spiritual affairs, so the Empire under Constantine was a manifestation of the Kingdom on Earth to rule in civil affairs. God would use both to accomplish his redemptive plan. And just as God ruled in Heaven, Constantine ruled on Earth. He’s not a god, as some of the earlier emperors had claimed, but he is, Eusebius reasoned, God’s unique agent to administer His Kingdom on earth.

These ideas of monarchy and kingship Eusebius promoted about the Emperor played well in the East where monarchs had long been esteemed as semi-divine. But Rome’s historic aversion to kings, its allergic reaction to monarchy, meant Eusebius’s promotion of Constantine didn’t go over as well in the West. This is another factor that added to Constantine’s tendency to stay in the East. Eusebius’s promotion of Constantine as the leader of both Church & State set the scene for the emergence of one man to whom the Church would look for leadership. If not the Emperor, then another dynamic church leader; a bishop of the bishops.

When Constantine died in 337, the empire was split between his 3 sons, who each lined up behind a pro- or anti-Nicean stance. Eventually one of them, the Pro-Arian Constantius, aserted sole authority. But immediately after Constantine’s death, many church leaders were allowed to return to their homes from exile, including Athanasius. His enemy, the pro-Arian Eusebius moved from Nicomedia to the capital at Constantinople where he convinced Constantius to once more banish him. Athanasius knew Eusebius was moved by sheer political will and went à to Rome to plead his case.

In 340 Council of Western Bishops was convened that reversed Athanasius’s excommunication and reaffirmed the doctrinal position of the Nicene Creed. This was a gauntlet hurled to the ground before the Eastern churches who were by now leaning decidedly toward Arianism. They counted the Emperor as a chief defender & advocate. The Eastern bishops asked a crucial question; one that becomes central in the decades that followed. It was this: What gave Rome the right to overrule their decisions? After all, Athanasius was Bishop of Alexandria, an eastern city. He was their problem, not Rome’s. So how did the West think it could meddle in Eastern affairs? And besides, “Do you guys in Rome really want to mess with the Emperor? He is after all, our guy.”

The following year, 341, the Eastern bishops called their own council in Antioch to counter Rome’s. Interestingly, when they sat down to establish an official position on Arianism, they realized it couldn’t be supported and repudiated it instead. Discussions revealed they weren’t pro-Arian so much as uncomfortable with the way the deity of Christ had been put at Nicaea. It’s like the members of a family each thinking, “Fish. I haven’t had fish for a while. I should have some fish.” But then when they all talk about where they want to go for dinner on Saturday night, they agree what they really want is prime rib. Eusebius was clearly pro-Arian & had the Emperor’s ear. But when the other Eastern bishops gathered, they realized they didn’t really want his fishy-Arianism. What they wanted was the prime-rib The Nicean Creed had sought to serve but ended up dishing burger. So the 341 Council of Antioch repudiated Arianism. But they were going to have none of Rome’s meddling in their affairs & refused to reverse Athanasius’ exile. Ultimately, the Council of Antioch failed in that they were unable to offer a creedal statement that improved on or fixed the problems they had with the Nicene Creed. Their efforts ended up only adding to the confusion on what Christians believed about Jesus.

At the prompting of his brother Constans, Constantius called for a Council of both Eastern & Western bishops at Sardica (SAR–dee-ka) in modern Bulgaria just a year after Antioch. This Council accomplished nothing but to further divide East from West. Though a temporary calm ensued, the fracture between the 2 halves of the Empire revealed at Sardica only became more pronounced in the decades that followed. It was never healed.

Athanasius returned to Alexandria yet again, only to be banished a few years later when Constantius took control of the Western Empire from his brother. Constantius then allowed his Arian friends to dictate policy in the West as they’d been in the East. Nicene bishops were replaced by Arians. Athanasius was again condemned and banished. You have to feel for this poor guy who just wanted to take care of his flock, but could not sit idly by & watch corrupt men make war on the Truth for political gain.

As Constantius’ reign entered its last years, he forced a couple more councils to adopt the Arian-backed word ‘homoi-ousias’ to describe Jesus as being of similar substance with the Father rather than the Nicean formulation of ‘homo-ousias’ – ONE & the same substance as the Father. And again, as at Nicea, this terminology was rammed down the Bishops’ throats. As happened after Nicaea, they went away from the councils resentful of being pressed to accept a doctrine they couldn’t support. The effect was the exact opposite of what Constantius & his Arian priest Eusebius wanted. The bishops retreated to the Nicean Creed. “Homo-ousias might not be precisely how they’d describe Jesus’ deity, but it was better than the newly required “homoi-ousias” and would have to suffice until someone could come up with a better way to state it.

That better formulation of the deity of Christ came from the 3 bishops who took up the Nicean standard after Athanasius died. We’ll take them up next time.

As we close it out, I want to thank those who’ve recommended the podcast to others.

It’s great seeing all those who go to the Facebook page, give CS a “like” and leave a comment about where they live.

Because of the growth of the podcast and the bandwidth required to host it, we’ve needed to add a DONATE feature. What used to be a labor of love that I was more than happy to fund has become a labor of love that now needs your assistance. So, if you can, please go to sanctorum.us and follow the link to donate. Any amount is a help. Thanks.