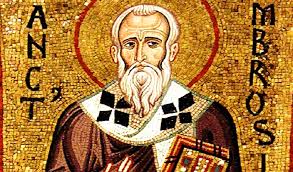

The title of this episode is simply à “Ambrose.” And once we learn a little about him, we’ll see that title is enough.

For Ambrose was one of the most interesting figures in Church History, a hinge around which the course of the Faith swung.

Born in 340, Ambrose was the second son of Ambrosius, the imperial governor of Gaul and part of an ancient Roman family that included the famous Marcus Aurelius. Not long after Aurelius, and his disastrous son and heir Commodus, the family became Christians who provided not a few notable martyrs. Ambrose was born at Trier, the imperial capital of Gaul. While still a child, Ambrose’s father died, and he was taken to Rome to be raised. His childhood was spent in the company of many members of the Christian clergy, men of sincere faith with a solid grasp on the theological challenges the Church of that day wrestled with; things you’re familiar with because we’ve spent the last several episodes dealing with them; that is, the Christological controversies that swirled first around Arius, then the blood-feud between Cyril & Nestorius.

Now would be a good time for me to toss in some place-markers so we can get a sense of what was going on as Ambrose grew up. Donatus is the bishop of Carthage. The Cappadocian Fathers, Basil, and the 2 Gregory’s are hammering out the proper verbiage to understand the Trinity. Athanasius has his long run as THE chief defender or Biblical orthodoxy. When Ambrose was 16, the famous Desert Father Anthony of Egypt died. The Goths ran rampant over Northern Europe, causing great consternation in the Roman Empire. When Ambrose was 38 the Goths defeated the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople in a loss so thorough, the Emperor Valens was killed.

During Ambrose’s lifetime, Pope Damasus will rule the Church at Rome. Jerome will move to Bethlehem and complete the Vulgate. John Chrysostom will serve as Patriarch at Constantinople.

Clearly, a lot with major import was going on during Ambrose’s lifetime.

When he turned 30, Ambrose, based in the capital at Milan, became governor of all NW’n Italy. He was charged with the responsibility to officiate church disputes. This was at a time when Nicaean & Arian believers were at war with each other; a war not fought with literal weapons but with words. Ambrose was no friend to the Arians, but he was so fair-minded and well-regarded, both sides supported him in his role as governor. When the Arian bishop of Milan died, Ambrose attended the meeting to elect his replacement, hoping his presence would forestall violence. To his surprise, both sides shouted their wish that he be the replacement.

Ambrose didn’t want it. He was doing quite well as a political leader. Following the practice of many at that time, he hadn’t even been baptized yet. But the people wrote to Emperor Valentinian, asking for his approval of their selection. Ambrose was placed under arrest until he agreed to serve a Milan’s new bishop.

Now, if the Arians had hoped to gain favor by supporting Ambrose as bishop, they were destined to disappointment. Their new bishop helped define what the word ‘orthodox’ meant. He soon took the Arians to task & refused to surrender a building for them to meet in. He wrote several works against them that went on to prove instrumental in ultimately bringing an end to Arianism.

Trained in rhetoric and law, and having studied Greek, Ambrose became known for his knowledge of Greek scholars, both Christian and pagan. In addition to Philo, Origen, and Basil of Caesarea, he quoted the Neo-platonist Plotinus in his sermons. He was widely regarded as an excellent preacher.

In many of his messages, Ambrose expounded upon the virtues of asceticism. He was so persuasive that noble families sometimes forbade their daughters to attend his services, fearing they’d trade their marriageable status withy its potential for a bride price, for the life of nun.

One piece of his pastoral advice became a maxim for the clergy: “When you are at Rome, live in the Roman style; when you are elsewhere, live as they live elsewhere.”

Ambrose also introduced congregational singing, and was accused of “bewitching” Milan by introducing Eastern melodies into the hymns he wrote. Because of his influence, hymn-singing became an important part of Western liturgy.

While Ambrose was a fierce opponent of heresy, as seen in his stand against Arianism, his opposition to religious issues didn’t morph over into how people were treated civilly. Arians & pagans were still citizens who possessed rights as citizens. As human beings, they were still objects of God’s love and desire for salvation. Respect needed to be shown them, even while opposing them theologically. That was a rare perspective for the time; inordinately rare. And it earned Ambrose tremendous respect from all quarters.

While the people of Ambrose’s time credited his writings and worship innovations as the most notable feature of his life & ministry, history attributes two other momentous events to his impact on the Church.

First is in the realm of church-state relations.

Second would be his influence on a young pagan who visited his church and became a follower of Jesus. His name was Augustine.

Let’s consider first, Ambrose’s impact of church-state relations.

His relationship with Emperor Theodosius, who finalized a long-running political trend of folding the Roman Empire into a Christian state, was a dramatic shift from the first 200 years of Church history that saw an on & off persecution.

An example of the change from paganism to Christianity occurred in 390, when local officials imprisoned a charioteer of Thessalonica for homosexual behavior. The public rebelled against this action because the charioteer was a major celebrity, a sports hero & crowd favorite. Riots broke out w/a loud cry for his release. Not a few of the rioters and innocent bystanders were killed, including the governor. The mob took over the prison and the prisoner was freed.

The Emperor was enraged by the melee. He was determined to exact revenge against the people of Thessalonica for such a flagrant disregard for the law and the disrespect he felt at having his hand-picked governor so casually relieved of life. So he slyly announced another chariot race. When the crowds showed up & settled into their seats, the gates were locked, the people inside—massacred. Over the following 3 hours, 7,000 were put to the sword.

Ambrose was stunned! Once he recovered from his shock, he sat down and composed a letter to Theodosius, demanding the Emperor repent. As chief ruler, Theodosius wasn’t inclined to follow some far-off bishop’s counsel. Ambrose was merely a clergyman in Milan, Italy; Theodosius was the mighty ruler headquartered in the East at Constantinople.

But Theodosius didn’t stay in Constantinople. Wouldn’t you just know it? Imperial business took him, guess where! Yep – Milan. As a Christian Emperor of a now Christian Empire, Theodosius went to church, and expected Pastor Ambrose to serve him Communion. Ambrose refused! His letter calling for the Emperor to repent had gone unheeded. Who did this guy think he was that he could just waltz into the church in Milan and line up for Communion as though everything was hunky-dory? The nerve of the guy!

Ambrose repeated the condition: Unless the emperor repent of his gross abuse of power, & do so publicly, no Communion would pass his lips! Either Ambrose was gutsy or had a death wish! An Emperor who’d ordered the execution of thousands probably wouldn’t think much of offing a lone, obstinate bishop. But Ambrose demonstrated he would not compromise his calling to save his life and Theodosius realized his best course was to do as instructed and repented by setting aside his royal garments & emblems of State, wearing humble sackcloth, & a face streaked w/ash as a sign of penance.

Ambrose never intended this humiliation of the Emperor as a way to elevate himself or other church officials. It was simply something he believed Theodosius, who claimed to be a Christian, was required to do as a sign of sincere contrition before God. Ambrose would have been appalled at how later bishops used their office & power to administer the sacraments as a way to manipulate civil rulers, and by doing so, use civil power to accomplish church ends. Or we should say, their own ends hidden ‘neath a thin veneer of religion.

Though Ambrose could not have foreseen the consequences of this episode with the Emperor, it introduced the medieval concept of a Christian emperor as the compliant “son of the church serving under orders from Christ.” Over the next millennium, secular and religious rulers vied with each other over who was sovereign in the different spheres of life.

Though we might expect Emperor Theodosius to leave Milan with an axe to grind as it related to Ambrose, legend says he was so impressed with Ambrose’s courage & quality of Christian witness he said, “I know no bishop worthy of the name, except Ambrose” When the emperor died, it was in Ambrose’s arms. Of Theodosius’ death Ambrose said, “I confess I loved him, and felt the sorrow of his death in the abyss of my heart.”

Two years later, Ambrose himself fell ill. The worries the entire Italian countryside felt were expressed by one writer as; “When Ambrose dies, we shall see the ruin of Italy.” On the Eve of Easter in 397, Milan’s beloved bishop breathed his last.

Only one name is more associated with Ambrose than Theodosius’. And that leads us to the second impact of his ministry, the one historians reckon as most important. That one name is the student who outshined this teacher: Augustine. But that’s the subject of our next few episode . . .