This 62nd episode of CS is the 5th and final in our look at monasticism in the Middle Ages.

To a lesser extent for the Dominicans but a bit more for the Franciscans, monastic orders were an attempt to bring reform to the Western Church which during the Middle Ages had fallen far from the Apostolic ideal. The institutional Church had become little more than one more political body, with vast tracts of land, a massive hierarchy, a complex bureaucracy, and had accumulated powerful allies and enemies across Europe. The clergy and older orders had degenerated into an illiterate fraternity. Many priests and monks could neither read nor write, and engaged in gross immorality while hiding behind their vows.

It wasn’t this case everywhere. But it was in enough places that Francis was compelled to use poverty as a means of reform. The Franciscans who followed after Francis were quickly absorbed back into the Church’s structure and the reforms Francis envisioned were still-born.

Dominic wanted to return to the days when literacy and scholarship were part and parcel of clerical life. The Dominicans carried on his vision, but when they became prime agents of the Inquisition, they failed to balance truth with grace.

Modern depictions of medieval monks often cast them in a stereo-typical role as either sinister agents of immorality, or bumbling fools with good hearts but soft heads. Sure there were some of each, but there were many thousands who were sincere followers of Jesus and did their best to represent Him.

There’s every reason to believe they lived quietly in monasteries and convents; prayed, read and engaged in humble manual labor throughout their lives. There were spiritual giants as well as thoroughly wicked and corrupt wretches.

After Augustine of Canterbury brought the Faith to England it was as though the sun had come out.

Another among God’s champions was Malachi, whose story was recounted by Bernard of Clairvaux in the 12th C. Stories like his were one of the main attractions for medieval people who looked to the saints for reassurance some had managed to lead exemplary lives, and shown others how to.

The requirement of sanctity was easy to stereotype. In the Life of St Erkenwald, we read that he was “perfect in wisdom, modest in conversation, vigilant in prayer, chaste in body, dedicated to holy reading, rooted in charity.” By the late 11th C, it was even possible to hire a hagiographer, a writer of saintly-stories, such as Osbern of Canterbury, who would, for a fee, write a Life of a dead abbot or priest, in the hope he’d be canonized, that is – declared by the Church to be a saint.

There was strong motive to do this. Where there’d been a saint, a shrine sprang up, marking with a monument his/her monastery, house, bed, clothes and relics. All were much sought after as objects veneration. Pilgrimages were made to the saint’s shrine. Money dropped in the ubiquitous moneybox. But it wasn’t just a church or shrine that benefited. The entire town prospered. After all, pilgrims needed a place to stay, food to eat, souvenirs to take home proving they’d performed the pilgrimage and racked up spiritual points. Business boomed! So, hagiographers included a list of miracles the saint performed. These miracles were evidence of God’s approval. There was competition between towns to see their abbot or priest canonized because it meant pilgrims flocking to their city.

It was assumed that a holy man or woman left behind, in objects touched or places visited, a residual spiritual power, a ‘merit’, which the less pious could acquire for assistance in their own troubles by going on pilgrimage and praying at the shrine. A similar power inhered in the body of the saint, or in parts of the body; fingernails or hair, which could conveniently be kept in ‘relic-holders’ called reliquaries. People prayed near and touching them in the hope of a miracle, a healing, or help in some other urgent request of God.

The balance between the active and the contemplative life was the core issue for those who aspired to be a genuine follower of Jesus and a good example to others. They struggled with the question of how much time should be given to God and how much to work in the world? From the Middle Ages, there comes no account of the enlightened idea the secular and religious could be merged into one overall passion for and service of God.

In the medieval way of thinking, to be truly godly, a sequestered religious life was required. The idea that a blacksmith could worship God while working at his anvil was nowhere in sight. Francis came closest, but even he considered working for a wage and the call to glorify God mutually exclusive. Francis urged work as part of the monk’s life, but depended on charity for support. It wouldn’t be till the Reformation that the idea of vocation liberated the sanctity of work.

Because the cloistered, or sequestered religious life, was regarded as the only way to please God, many of the greats from the 4th C on supported monasticism. I list now some names who held this view, trusting if you’ve listened to the podcast for a while you’ll recognize them . . .

St. Anthony of Egypt, Athanasius, Basil, Gregory of Nyssa, Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Benedict of Nursia.

In the Middle Ages the list is just as imposing. Anselm, Albertus Magnus, Bonaventura, Thomas Aquinas, and Duns Scotus, St. Bernard and Hugo de St. Victor, Eckart, Tauler, Hildegard, Joachim of Flore, Adam de St. Victor, Anthony of Padua, Bernardino of Siena, Berthold of Regensburg, Savonarola, and of course, Francis and Dominic.

The Middle Ages were a favorable period for the development of monastic communities. The religious, political and economic forces at work across Europe conspired to make monastic life for both men and women a viable, even preferred, option. As is so often the case in movies and books depicting this period, sure there were some young men and women who balked at entering a monastery or convent when forced by parents, but there were far more who wanted to engage the sequestered life who were denied by parents. When war decimated the male population and women outnumbered men by large margins, becoming a nun was the only way to survive. Young men who knew they weren’t cut out for the hard labor of farm life or military service could always find a place to pursue their passion for learning in a monastery.

As in most institutions, the fate of the brothers and sisters depended on the quality of their leader, the abbot or abbess. If she was a godly and effective leader, the convent thrived. If he was a tyrannical brute, the monastery shriveled.

In those monasteries where scholarship prevailed, ancient manuscripts were preserved by scribes who laboriously copied them, and by doing so, became well-versed in the classics. It was from these intellectual safe-houses the Renaissance would eventually emerge.

By drawing to themselves the best minds of the time, from the 10th well into the 13th C, monasteries were the nursery of piety and the centers of missionary and civilizing energy. When there was virtually no preaching taking place in churches, the monastic community preached powerful sermons by calling men’s thoughts away from war and bloodshed to brotherhood and religious devotion. The motto of some monks was, “by the plough and the cross.” In other words, they were determined to build the Kingdom of God on Earth by preaching the Gospel and transforming the world by honest and hard, humble work.

Monks were pioneers in the cultivation of the ground, and after the most scientific fashion then known, taught agriculture, the tending of vines and fish, the breeding of cattle, and the manufacture of wool. They built roads and some of the best buildings. In intellectual and artistic concerns, the convent was the main school of the times. It trained architects, painters, and sculptors. There the deep problems of theology and philosophy were studied; and when the universities arose, the convent furnished them with their first and most renowned teachers.

So popular was the monastic life that religion seemed to be in danger of running out into monkery and society of being little more than a collection of convents. The 4th Lateran Council tried to counter this tendency by forbidding the establishment of new orders. But no council was ever more ignorant of the immediate future. Innocent III was scarcely in his grave before the Dominicans and Franciscans received full papal sanction.

During the 11th and 12th Cs an important change came. All monks were ordained as priests. Before that time it was the exception for a monk to be a priest, which meant they weren’t allowed to offer the sacraments. Once they were priests, they could.

The monastic life was praised as the highest form of earthly existence. The convent was compared to The Promised Land and treated as the shortest and surest road to heaven. The secular life, even the life of the secular priest, was compared to Egypt. The passage to the cloister was called conversion, and monks were converts. They reached the Christian ideal.

The monastic life was likened to the life of the angels. Bernard said to his fellow monks, “Are you not already like the angels of God, having abstained from marriage.”

Even kings and princes desired to take the monastic vow and be clad in the monk’s habit. So even though Frederick II was a bitter foe of the Pope as he neared his death, he changed into the robes of a Cistercian monk. Rogers II and III of Sicily, along with William of Nevers all dressed up in monks robes as their end drew near. They thought doing so would mean a better chance at heaven. Spiritual camouflage to get past Peter.

Accounts from the time make miracles part and parcel of the monk’s daily life. He was surrounded by spirits. Visions and revelations occurred day and night. Devils roamed about at all hours in the cloistered halls. They were on evil errands to deceive the unwary and shake the faith of the careless. Elaborate accounts of these encounters are given by Peter the Venerable in his work on Miracles. He gives a detailed account of how these restless spiritual foes pulled the bedclothes off sleeping monks and, chuckling, left them across the cloister.

While monasteries and convents were a major part of life in Middle Age Europe, many of them bastions of piety and scholarship, others didn’t live up to that rep and became blockades to progress. As the years marched forward, the monastic ideal of holiness degenerated into a mere form that became superstitious and suspicious of anything new. So while some monasteries served as mid-wives to the Renaissance others were like Herod’s soldiers trying to slay it in its infancy.

As we end, I thought it good to do a brief review of what are called “the hours, the Divine Office or the breviary.” This was how monks and nuns divided their day.

The time for these divisions varied from place to place but generally it went like this.

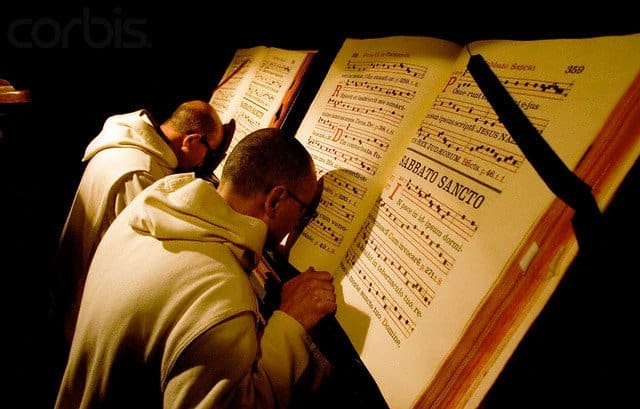

In the early morning before dawn, a bell was rung that awakened the monks or nuns to a time of private reading and meditation. Then they all gathered for Nocturns, in which a psalm was read, there was chanting, then some lessons form Scripture or the Church Fathers.

After that they went back to bed for a bit, then got up at dawn for another service called Lauds. Lauds was followed by another period of personal reading and prayer, which resolved in the cloister again gathering for Prime at 6 AM.

Prime was followed by a period of work, which ended with Terce, a time for group prayer at about 9.

Then there’s more work from about 10 to just before Noon, when the nuns and brothers gather for Sext, a short service where a few psalms are read. That’s followed by the mid-day meal, a nap, another short service at about 3 PM called None, named for the 9th hour since dawn.

Then comes a few hours of work, dinner about 5:50, and Vespers at 6 PM.

After Vespers the nuns and monks have a time of personal, private prayers; regather for the brief service Compline, then hit the sack.

Protestants and Evangelicals might wonder where the idea for the canonical hours came from. There’s some evidence they derived from the practice of the Apostles, who as Jews, observed set times during the day for prayer. In Acts 10 we read how Peter prayed at the 6th hour. The Roman Centurion Cornelius, who’d adopted the Jewish faith, prayed at the 9th hour. In Acts 16, Paul and Silas worshipped at Midnight; though that may have been because they were in stocks in the Philippian jail. As early as the 5th C, Christians were using references in the Psalms as cues to pray in the morning, at mid-day and at midnight.