by Lance Ralston | Nov 9, 2014 | English |

This 62nd episode of CS is the 5th and final in our look at monasticism in the Middle Ages.

To a lesser extent for the Dominicans but a bit more for the Franciscans, monastic orders were an attempt to bring reform to the Western Church which during the Middle Ages had fallen far from the Apostolic ideal. The institutional Church had become little more than one more political body, with vast tracts of land, a massive hierarchy, a complex bureaucracy, and had accumulated powerful allies and enemies across Europe. The clergy and older orders had degenerated into an illiterate fraternity. Many priests and monks could neither read nor write, and engaged in gross immorality while hiding behind their vows.

It wasn’t this case everywhere. But it was in enough places that Francis was compelled to use poverty as a means of reform. The Franciscans who followed after Francis were quickly absorbed back into the Church’s structure and the reforms Francis envisioned were still-born.

Dominic wanted to return to the days when literacy and scholarship were part and parcel of clerical life. The Dominicans carried on his vision, but when they became prime agents of the Inquisition, they failed to balance truth with grace.

Modern depictions of medieval monks often cast them in a stereo-typical role as either sinister agents of immorality, or bumbling fools with good hearts but soft heads. Sure there were some of each, but there were many thousands who were sincere followers of Jesus and did their best to represent Him.

There’s every reason to believe they lived quietly in monasteries and convents; prayed, read and engaged in humble manual labor throughout their lives. There were spiritual giants as well as thoroughly wicked and corrupt wretches.

After Augustine of Canterbury brought the Faith to England it was as though the sun had come out.

Another among God’s champions was Malachi, whose story was recounted by Bernard of Clairvaux in the 12th C. Stories like his were one of the main attractions for medieval people who looked to the saints for reassurance some had managed to lead exemplary lives, and shown others how to.

The requirement of sanctity was easy to stereotype. In the Life of St Erkenwald, we read that he was “perfect in wisdom, modest in conversation, vigilant in prayer, chaste in body, dedicated to holy reading, rooted in charity.” By the late 11th C, it was even possible to hire a hagiographer, a writer of saintly-stories, such as Osbern of Canterbury, who would, for a fee, write a Life of a dead abbot or priest, in the hope he’d be canonized, that is – declared by the Church to be a saint.

There was strong motive to do this. Where there’d been a saint, a shrine sprang up, marking with a monument his/her monastery, house, bed, clothes and relics. All were much sought after as objects veneration. Pilgrimages were made to the saint’s shrine. Money dropped in the ubiquitous moneybox. But it wasn’t just a church or shrine that benefited. The entire town prospered. After all, pilgrims needed a place to stay, food to eat, souvenirs to take home proving they’d performed the pilgrimage and racked up spiritual points. Business boomed! So, hagiographers included a list of miracles the saint performed. These miracles were evidence of God’s approval. There was competition between towns to see their abbot or priest canonized because it meant pilgrims flocking to their city.

It was assumed that a holy man or woman left behind, in objects touched or places visited, a residual spiritual power, a ‘merit’, which the less pious could acquire for assistance in their own troubles by going on pilgrimage and praying at the shrine. A similar power inhered in the body of the saint, or in parts of the body; fingernails or hair, which could conveniently be kept in ‘relic-holders’ called reliquaries. People prayed near and touching them in the hope of a miracle, a healing, or help in some other urgent request of God.

The balance between the active and the contemplative life was the core issue for those who aspired to be a genuine follower of Jesus and a good example to others. They struggled with the question of how much time should be given to God and how much to work in the world? From the Middle Ages, there comes no account of the enlightened idea the secular and religious could be merged into one overall passion for and service of God.

In the medieval way of thinking, to be truly godly, a sequestered religious life was required. The idea that a blacksmith could worship God while working at his anvil was nowhere in sight. Francis came closest, but even he considered working for a wage and the call to glorify God mutually exclusive. Francis urged work as part of the monk’s life, but depended on charity for support. It wouldn’t be till the Reformation that the idea of vocation liberated the sanctity of work.

Because the cloistered, or sequestered religious life, was regarded as the only way to please God, many of the greats from the 4th C on supported monasticism. I list now some names who held this view, trusting if you’ve listened to the podcast for a while you’ll recognize them . . .

St. Anthony of Egypt, Athanasius, Basil, Gregory of Nyssa, Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Benedict of Nursia.

In the Middle Ages the list is just as imposing. Anselm, Albertus Magnus, Bonaventura, Thomas Aquinas, and Duns Scotus, St. Bernard and Hugo de St. Victor, Eckart, Tauler, Hildegard, Joachim of Flore, Adam de St. Victor, Anthony of Padua, Bernardino of Siena, Berthold of Regensburg, Savonarola, and of course, Francis and Dominic.

The Middle Ages were a favorable period for the development of monastic communities. The religious, political and economic forces at work across Europe conspired to make monastic life for both men and women a viable, even preferred, option. As is so often the case in movies and books depicting this period, sure there were some young men and women who balked at entering a monastery or convent when forced by parents, but there were far more who wanted to engage the sequestered life who were denied by parents. When war decimated the male population and women outnumbered men by large margins, becoming a nun was the only way to survive. Young men who knew they weren’t cut out for the hard labor of farm life or military service could always find a place to pursue their passion for learning in a monastery.

As in most institutions, the fate of the brothers and sisters depended on the quality of their leader, the abbot or abbess. If she was a godly and effective leader, the convent thrived. If he was a tyrannical brute, the monastery shriveled.

In those monasteries where scholarship prevailed, ancient manuscripts were preserved by scribes who laboriously copied them, and by doing so, became well-versed in the classics. It was from these intellectual safe-houses the Renaissance would eventually emerge.

By drawing to themselves the best minds of the time, from the 10th well into the 13th C, monasteries were the nursery of piety and the centers of missionary and civilizing energy. When there was virtually no preaching taking place in churches, the monastic community preached powerful sermons by calling men’s thoughts away from war and bloodshed to brotherhood and religious devotion. The motto of some monks was, “by the plough and the cross.” In other words, they were determined to build the Kingdom of God on Earth by preaching the Gospel and transforming the world by honest and hard, humble work.

Monks were pioneers in the cultivation of the ground, and after the most scientific fashion then known, taught agriculture, the tending of vines and fish, the breeding of cattle, and the manufacture of wool. They built roads and some of the best buildings. In intellectual and artistic concerns, the convent was the main school of the times. It trained architects, painters, and sculptors. There the deep problems of theology and philosophy were studied; and when the universities arose, the convent furnished them with their first and most renowned teachers.

So popular was the monastic life that religion seemed to be in danger of running out into monkery and society of being little more than a collection of convents. The 4th Lateran Council tried to counter this tendency by forbidding the establishment of new orders. But no council was ever more ignorant of the immediate future. Innocent III was scarcely in his grave before the Dominicans and Franciscans received full papal sanction.

During the 11th and 12th Cs an important change came. All monks were ordained as priests. Before that time it was the exception for a monk to be a priest, which meant they weren’t allowed to offer the sacraments. Once they were priests, they could.

The monastic life was praised as the highest form of earthly existence. The convent was compared to The Promised Land and treated as the shortest and surest road to heaven. The secular life, even the life of the secular priest, was compared to Egypt. The passage to the cloister was called conversion, and monks were converts. They reached the Christian ideal.

The monastic life was likened to the life of the angels. Bernard said to his fellow monks, “Are you not already like the angels of God, having abstained from marriage.”

Even kings and princes desired to take the monastic vow and be clad in the monk’s habit. So even though Frederick II was a bitter foe of the Pope as he neared his death, he changed into the robes of a Cistercian monk. Rogers II and III of Sicily, along with William of Nevers all dressed up in monks robes as their end drew near. They thought doing so would mean a better chance at heaven. Spiritual camouflage to get past Peter.

Accounts from the time make miracles part and parcel of the monk’s daily life. He was surrounded by spirits. Visions and revelations occurred day and night. Devils roamed about at all hours in the cloistered halls. They were on evil errands to deceive the unwary and shake the faith of the careless. Elaborate accounts of these encounters are given by Peter the Venerable in his work on Miracles. He gives a detailed account of how these restless spiritual foes pulled the bedclothes off sleeping monks and, chuckling, left them across the cloister.

While monasteries and convents were a major part of life in Middle Age Europe, many of them bastions of piety and scholarship, others didn’t live up to that rep and became blockades to progress. As the years marched forward, the monastic ideal of holiness degenerated into a mere form that became superstitious and suspicious of anything new. So while some monasteries served as mid-wives to the Renaissance others were like Herod’s soldiers trying to slay it in its infancy.

As we end, I thought it good to do a brief review of what are called “the hours, the Divine Office or the breviary.” This was how monks and nuns divided their day.

The time for these divisions varied from place to place but generally it went like this.

In the early morning before dawn, a bell was rung that awakened the monks or nuns to a time of private reading and meditation. Then they all gathered for Nocturns, in which a psalm was read, there was chanting, then some lessons form Scripture or the Church Fathers.

After that they went back to bed for a bit, then got up at dawn for another service called Lauds. Lauds was followed by another period of personal reading and prayer, which resolved in the cloister again gathering for Prime at 6 AM.

Prime was followed by a period of work, which ended with Terce, a time for group prayer at about 9.

Then there’s more work from about 10 to just before Noon, when the nuns and brothers gather for Sext, a short service where a few psalms are read. That’s followed by the mid-day meal, a nap, another short service at about 3 PM called None, named for the 9th hour since dawn.

Then comes a few hours of work, dinner about 5:50, and Vespers at 6 PM.

After Vespers the nuns and monks have a time of personal, private prayers; regather for the brief service Compline, then hit the sack.

Protestants and Evangelicals might wonder where the idea for the canonical hours came from. There’s some evidence they derived from the practice of the Apostles, who as Jews, observed set times during the day for prayer. In Acts 10 we read how Peter prayed at the 6th hour. The Roman Centurion Cornelius, who’d adopted the Jewish faith, prayed at the 9th hour. In Acts 16, Paul and Silas worshipped at Midnight; though that may have been because they were in stocks in the Philippian jail. As early as the 5th C, Christians were using references in the Psalms as cues to pray in the morning, at mid-day and at midnight.

by Lance Ralston | Nov 2, 2014 | English |

This episode is titled, Dominic and continues our look on monastic life.

In our last episode, we considered Francis of Assisi and the monastic order that followed him, the Franciscans. In this installment, we take a look at the other great order that developed at that time; the Dominicans.

Dominic was born in the region of Castile, Spain in 1170. He excelled as a student at an early age. A priest by the age of 25, he was invited by his bishop to accompany him on a visit to Southern France where he ran into a group of supposed-heretics known as the Cathars. Dominic threw himself into a Church-sanctioned suppression of the Cathars through a preaching tour of the region.

Dominic was an effective debater of Cathar theology. He persuaded many who’d leaned toward their sect to instead walk away. These converts became zealous in the resistance against them. For this, the Bishop of Toulouse gave Dominic 1/6th of the diocesan tithes to continue his work. Another wealthy supporter gave Dominic a house in Toulouse so he could live and work at the center of controversy.

We’ll come back to the Cathars in a future episode.

Dominic visited Rome during the 4th Lateran Council, the subject of another future episode. He was encouraged by Pope Innocent III in his apologetic work but was refused in his request to start a new monastic order. The Pope suggested he instead join one of the existing orders. Since a Pope’s suggestion is really a command, Dominic chose the Augustinians. He donned their black monk’s habit and built a convent at Toulouse.

He returned to Rome a year later, staying for about a half year. The new Pope Honorius II granted his petition to start a new order. Originally called the “Order of Preaching Brothers,” it was the first religious community dedicated to preaching. The order grew rapidly in the 13th C, gaining 15,000 members in 557 houses by the end of the century.

When he returned to France, Dominic began sending monks to start colonies. The order quickly took root in Paris, Bologna, and Rome. Dominic returned to Spain where in 1218 he established separate communities for women and men.

From France, the Dominicans launched into Germany. They quickly established themselves in Cologne, Worms, Strasbourg, Basel, and other cities. In 1221, the order was introduced in England, and at once settled in Oxford. The Blackfriars Bridge, London, carries in its name the memory of their priory there.

Dominic died at Bologna in August, 1221. His tomb is decorated by the artwork of Nicholas of Pisa and Michaelangelo. Compared to the speedy recognition of Francis as a saint only two years after his death, Dominic’s took thirteen years; still a quick canonization.

Dominic lacked the warm, passionate concern for the poor and needy that marked his contemporary Francis. But if Francis was devoted to Lady Poverty, Dominic was pledged to Sir Truth. If Francis and Dominic were part of a cruise ship’s crew; Francis would be the activities director, Dominic the lawyer.

An old story illustrates the contrast between them. Interrupted in his studies by the chirping of a sparrow, Dominic caught and plucked it. Francis, on the other hand, is revered for his tender compassion and care for all things. To this day he’s represented in art with a bird perched on his shoulder.

Dominic was resolute in purpose, zealous in propagating Orthodoxy, and devoted to the Church and its hierarchy. His influence continues through the organization he created.

At the time of Dominic’s death, the preaching monks, or “friars” as they were called, had sixty monasteries and convents scattered across Europe. A few years later, they’d pressed to Jerusalem and deep into the North. Because the Dominicans were the Vatican’s preaching authority, they received numerous privileges to carry out their mission any and everywhere.

Mendicancy, that is begging as a means of support, was made the rule of the order in 1220. The example of Francis was followed, and the order as well as the individual monks renounced all right to personal property. However, this mendicancy was never emphasized among the Dominicans as it was among Franciscans. The obligation of corporate poverty was revoked in 1477. Dominic’s last exhortation to his followers was that they should love, service humbly, and live in poverty but to be frank, those precepts were never really taken much to heart by most of his followers.

Unlike Francis, Dominic didn’t require manual labor from the members of the order. He substituted study and preaching for labor. The Dominicans were the first monastics to adopt rules for studying. When Dominic founded his monastery in Paris, and sent seventeen of his order to staff it, he told them to “study and preach.” A theological course of four years in philosophy and theology was required before a license was granted to preach, and three years more of theological study followed.

Preaching and the saving of souls were defined as the chief aim of the order. No one was permitted to preach outside the cloister until he was 25. And they were not to receive money or other gifts for preaching, except food. Vincent Ferrer and Savonarola were the most renowned of the Dominican preachers of the Middle Ages. The mission of the Dominicans was mostly to the upper classes. They were the patrician order among the monastics.

Dominic would likely have been just one more nameless priest among thousands of the Middle Ages had it not been for that fateful trip to Southern France where he encountered the Cathars. He’d surely heard of them back in Spain but it was their popularity in France that provoked him. He saw and heard nothing among the heretics that he knew some good, solid teaching and preaching couldn’t correct. He was the right man, at the right time doing the right thing; at first. But his success at answering the errors of the Cathars gained him support that pressed him to step up his opposition toward error. That opposition would turn sinister and into what is arguably one of the dark spots on Church history – the Inquisition. Though hundreds of years have passed, the word still causes many to shiver in terror.

Dante said of Dominic he was, “Good to his friends, but dreadful to his enemies.”

We’ll take a closer look at the Inquisition in a later episode. For now à

In 1232, the conduct of the Inquisition was committed to the care of the Dominicans. Northern France, Spain, and Germany fell to their lot. The stern Torquemada was a Dominican, and the atrocious measures which he employed to spy out and punish ecclesiastical dissent an indelible blot on them.

The order’s device or emblem as appointed by the Pope was a dog with a lighted torch in its mouth. The dog represented the call to watch, the torch to illuminate the world. A painting in their convent in Florence represents the place the order came to occupy as hunters of heretics. It portrays dogs dressed in Dominican colors, chasing away heretic-foxes. All the while the pope and emperor, enthroned and surrounded by counselors, look on with satisfaction.

As we end this episode, I thought it wise to make a quick review of the Mendicant monastic orders we’ve been looking at.

First, the Mendicant orders differed from previous monastics in that they were committed, not just to individual but corporate poverty. The mendicant houses drew no income from rents or property. They depended on charity.

Second, the friars didn’t stay sequestered in monastic communes. Their task was to be out and about in the world preaching the Gospel. Because all of European society was deemed Christian, the mendicants took the entire world as their parish. Their cloister wasn’t the halls of a convent; it was the public marketplace.

Third, the rise of the universities at this time presented both the Franciscans and Dominicans with new opportunities to get the Gospel message out by educating Europe’s future generations.

Fourth, the mendicants promoted a renewal of piety by the Tertiary or third-level orders they set up, which allowed lay people an opportunity to attend a kind of monk-camp.

Fifth, The mendicants were directly answerable to the Pope rather than local bishops or intermediaries who often used orders to their own political and economic ends.

Sixth, the friars composed an order and organization more than a specific house as the previous orders had done. Before the mendicants, monks and nuns joined a convent or monastery. Their identity was wrapped up in that specific cloister. The Mendicants joined an order that was spread over dozens of such houses. Monks’ obedience was now not to the local abbot or abbess, but to the order’s leader.

Besides the Dominicans and Franciscans, other mendicant orders were the Carmelites, who began as hermits in the Holy Land in the 12th C; the Hermits of St. Augustine, and the Servites, who’d begun under the Augustinian rule in the 13th C, but became mendicants in the 15th.

by Lance Ralston | Oct 26, 2014 | English |

This Episode of CS is titled, Francis and continues our look at the mendicant orders.

Though we call him Francis of Assisi, his original name was Francesco Bernardone. Born in 1182, his given name was Giovanni (Latin of John). His father Pietro nicknamed him Francesco which is what everyone called him. Pietro was a wealthy dealer in textiles imported from France to their hometown of Assisi in central Italy.

His childhood was marked by the privileges of his family’s wealth. He wasn’t a great student, finding his delight more in having a good time entertaining friends. When a local war broke out, he signed up to fight for his and was taken prisoner. Released at 22, Francis then came down with a serious illness. That’s when he began to consider eternal things, as so many have when facing their mortality. He rose from his sick-bed disgusted with himself and unsatisfied with the world.

The war still on, he was on his way to rejoin the army when he turned back, sensing God had another path for him. He went into seclusion at a grotto near Assisi where his path forward became clearer. He decided to make a typical pilgrimage to Rome, where it was assumed the godly went to seek God. But there he was stuck by the terrible plight of the poor who lined the streets, many of them just outside the door of luxurious churches.

Confronted with a leper, he recoiled in horror. Then it dawned on him that his reaction was no different from an indifferent Church, which tolerated such gross need in their midst but doing nothing to lift the needy out of their condition. He turned around, kissed the leper’s hand, and left in it all the money he had.

Returning to Assisi, he attended the chapels in its suburbs instead of the main city church. There seemed less pretention in these humble chapels. He lingered most at the simply furnished St. Damian’s served by a single priest at a crude altar. This little chapel became a kind of Bethel for Francis; his bridge between heaven and earth.

The change that came over the one-time party-animal led to scorn and ridicule from those who’d known him. Privileged sons like Francis didn’t grovel in the mucky world of commoners; yet that was exactly what Francis was now doing. His father banished him from the family home. He renounced his obligations to them in public saying: “Up to this time I have called Pietro Bernardone ‘father,’ but now I desire to serve God and to say nothing else than ’Our Father which art in heaven.’” From then on, Francis was wholly devoted to a religious life. He dressed in beggar’s clothes, moved in with a small community of lepers, washed their sores, and restored the damaged walls of the chapel of St. Damian by begging building materials in the squares and streets of the city. He was 26 years old.

Francis then received from the Benedictine abbot of Mt. Subasio the gift of a little chapel called Santa Maria degli Angeli. Nicknamed the Portiuncula—the Little Portion. It became Francis’ favorite shrine. There he had most of his visions. It was there he eventually died.

While meditating one day in 1209, Francis heard the Words of Jesus to his followers, “Preach, the kingdom of heaven is at hand. Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, cast out devils. Provide neither silver nor gold, nor brass in your purses.” Throwing away his staff, purse, and, shoes, he made this the rule of his life. He preached repentance and gathered about him several companions. Their Rule was nothing less than full obedience to the Gospel.

Their mission was to preach, by both word and deed. Their constant emphasis was to make sure their lives exemplified the Word and Work of God. One saying attributed to him is: “Preach at all times. When necessary, use words.”

In 1210, Francis and some companions went to Rome were they were received by Pope Innocent III. The chronicle of the event reports that the pope, in order to test his sincerity, said, “Go, brother, go to the pigs, to whom you are more fit to be compared than to men, and roll with them, and to them preach the rules you have so ably set forth.” This may seem like a cruel put off, but it may in truth have been a test of Francis’ sincerity. He proposed a very different way than priests and monks had chosen. This command would certainly determine if Francis’ claim to poverty and obedience were genuine. Well, Francis DID obey, and returned saying, “My Lord, I have done so.” If the pope had only been mocking, Francis’ response softened him. He gave his blessing to the brotherhood and sanctioned their rule, granted them the right to cut their hair in the distinctive tonsure that was the badge of the monk, and told them to go and preach repentance.

The brotherhood increased rapidly. The members were expected to work. In his will, Francis urged the brethren to work at some trade as he’d done. He compared an idle monk to a drone. The brethren visited the sick, especially lepers who sat at the very bottom of the social order. They preached in ever expanding circles, and went abroad on missionary journeys. Francis was ready to sell the very ornaments of the altar rather than refuse an appeal for aid. He was ashamed when he encountered any one poorer than himself.

One of the most remarkable episodes of Francis’ career occurred at this time. He made a covenant, like marriage, with Poverty. He called it his bride, mother, and sister, and remained devoted to Sister Poverty with the devotion of a knight.

In 1217, Francis was presented to the new Pope Honorius III. At the advice of a powerful Cardinal who would later become Pope Gregory IX, he memorized his sermon. But when he appeared before the pontiff, he forgot it all and instead delivered an impromptu message, which won over the papal court.

Francis made evangelistic tours in 1219 thru Italy then into Egypt and Syria. Returning from the East with the title “il poverello” the little Poor Man, he found a new element had been introduced into the brotherhood thru the influence of a stern disciplinarian named Cardinal Ugolino, the same cardinal who’d coached him to memorize his sermon before the pope.

Francis was heart-broken over the changes made to his order. Passing through Bologna in 1220, he was deeply grieved to see a new house being built for the brothers. Cardinal Ugolino was determined to manipulate the Franciscans in the interest of the Vatican. Early on he’d offered Francis help to negotiate the intricacies of Vatican life and politics, and Francis accepted. Little did he realize he was inviting a force that would fundamentally alter all he stood for. Under the cardinal’s influence, a new code was adopted in 1221, then a third just two years later in which Francis’ distinctive perspective for the Franciscans was set aside. The original Rule of poverty was modified; the old ideas of monastic discipline re-introduced, and a new element of absolute submission to the pope added. The mind of Francis was too simple for the shrewd rulers of the church. His lack of guile couldn’t compete with men whose entire lives were lived wielding vast levers of political power. He was set aside and a member of the nobility was put at the head of the Order.

The forced subordination of Francis offers one of the most touching spectacles of medieval biography. Francis had withheld himself from papal privileges. He’d favored freedom of movement. But the deft hand of Cardinal Ugolino installed a strict monastic obedience. Organization replaced devotion. Ugolino probably did attempt to be a real friend to Francis but his loyalty was always and only to the Pope whom the Cardinal thought ought to be the undisputed ruler of all and every facet of Church life. It didn’t seem right to him that any monastic order wasn’t directly answerable to and controlled by the Pope. Ugolino laid the foundation of the cathedral in Assisi to Francis’ honor, and canonized him only two years after his death. But the Cardinal did not appreciate Francis’ humble spirit. Francis was helpless to carry out his original ideas, and yet, without making any outward sign of rebellion, he held them tightly to the end.

These ideas were affirmed in Francis’ famous will. This document is one of the most moving pieces of Christian literature. Francis called himself “little brother.” All he had to leave the brothers was his benediction, the memory of the early days of the brotherhood, and counsels to abide by their first Rule. This Rule, he said, he’d received from no human author. God himself had revealed it to him, that he ought to live according to the Gospel. He reminded them how the first members loved to live in poor and abandoned churches. He bade them not accept ornate churches or luxurious houses, in accordance with the rule of holy poverty they’d professed. He forbade their receiving special privileges from the Pope or his agents, even orders that gave them personal protection. Through the whole of the document there runs a note of anguish over the lost simplicity that had been the power of their first years; years when the presence of God had been so obvious and they had power to live the holy lives they longed for.

Francis’ heart was broken. Never strong, his last years were full of sicknesses. Change of location only brought temporary relief. The works of physicians, such as the age knew, were employed. But no wonder they didn’t help when you hear what they were: an iron, heated white-hot, was applied to his forehead.

As his body failed, he jokingly referred to it as Brother Ass.

Francis’s reputation as a saint preceded his death. We’ve talked about relics in previous episodes. But relics were always attributed to people dead for decades, usually hundreds of years. Francis was a living saint from whom people craved things like fragments of his clothing, hairs from his head, even the parings of his nails.

Two years before his death, Francis composed the hymn Canticle to the Sun, called by some the most perfect expression of religious feeling. It was written at a time when he was beset by temptations with blindness setting in. The hymn is a pious peal of passionate praise for nature, especially Brother Sun and Sister Moon.

The last week of his life, Francis asked for Psalm 142 to be read to him since his eyes were failing. Two brothers sang to him. That’s when a priest named Elias, loyal to Cardinal Ugolino and had advocated setting aside Francis’ original Rule in favor of the Cardinal’s more strict rule, rebuked Francis for making light of death and acting as though he wanted to die! “Why, what kind of faith did that reveal,” the indignant priest asked? It was thought unfitting for a saint. Francis replied that he’d been thinking of death for at least a couple years, and now that he was so united with the Lord, he ought to be joyful in Him. One witness at his bedside said when the time came, “he met death singing.”

Before Francis’ coffin was closed, great honors began to be heaped upon him. He was canonized only two years later.

The career of Francis of Assisi, as told by his contemporaries, and as his spirit is revealed in his own last testament, leaves the impression of purity, purpose, and humility of spirit; of genuine saintliness. He sought not positions of honor nor a place with the great. With a simple mind, he sought to serve his fellow-man by announcing the Gospel, and living out his understanding of it in his own example.

He sought to give the Gospel to the common people. They heard him gladly. He didn’t possess a great intellect but had a great soul.

He was no diplomat, but he was a man whose love for God and people was obvious to all who met him.

Francis wasn’t a theologian in the classic sense; someone who thought lofty thoughts. He was a practical theologian in that he lived the truths the best theology holds. He spoke and acted as one who feels full confidence in his mission. He spoke to the Church as no one after him did till Martin Luther came.

While history refers to the followers of Francis as the Franciscans, their official name was the fratres minores, the Minor Brethren, or simply the Minorites. When the order was first sanctioned by the Pope, Francis insisted on this as their title as a warning to the members not to aspire after positions of distinction.

They spread rapidly in Italy and beyond; but before Francis’ generation passed, the order was torn by the strife Cardinal Ugolino introduced. No other monastic order can show anything like long conflict within its own membership over a question of principle. The dispute had a unique place in the theological debates of the Middle Ages.

According to the founding Rule of 1210 and Francis’ last will, they were to be a free brotherhood devoted to poverty and the practice of the Gospel, rather than a closed organization bound by precise rules. Pope Innocent III who’d originally sanctioned them, urged Francis to take the rule of the older orders as his model, but Francis declined and went his own path. He built upon a few texts of Scripture. And as we said, just six years into the order’s life, Cardinal Ugolino installed a rigid discipline to the order, pushing aside Francis’ vision of a free brotherhood governed by grace instead of rules.

In 1217, the order began sending missionaries beyond Italy. Elias, a former mattress-maker in Assisi and one of Ugolino’s lackeys, led a band of missionaries to Syria. Others went to Germany, Hungary, France, Spain and England. The Franciscans proved to be courageous and entrepreneurial agents for the Gospel. They went south to Morocco and east as far as China. They accompanied Columbus on his 2nd journey to the New World and were active in early American missions from Florida to California, from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.

The Rule of 1221, second in the order’s history, shows two influences at work; one from Ugolino, the other of course from Francis. There are signs of the struggle which had already begun several years before. The Rule placed a general at the head of the order and a governing body or board was installed, made up of the heads of the order’s houses. Poverty was retained as a primary principle and the requirement of work remained. The sale of their products was forbidden except when it benefited the poor and needy.

The Rule of 1223, the third, was briefer but added even more organization to the order. It went further in erasing from the order the will of Francis. The mendicant or begging character of the order was emphasized. But obedience to the pope was introduced and a cardinal was made the order’s protector and guardian. Contrary to Francis’ will, a devotional book of prayers and hymns called the Roman Breviary was ordered to be used as the book of daily worship. Monastic discipline replaced Biblical liberty. The Rule of 1223 made clear the strong hand of papal hierarchy. The freedom of the 1210 Rule disappeared. The pope’s agents did everything they could to suppress Francis’ last testament since it was a passionate appeal for the original freedom of his brotherhood against the new order.

In light of the way the order was stolen out from under Francis’ leadership during his own lifetime, it’s a wonder they continued to be known as the Franciscans; they ought to have been called the Ugolinoians.

Alongside the male Franciscans were the Clarisses, nuns who took their name from Clara of Sciffi, canonized in 1255. Clara was so moved by Francis’ example she started a parallel order for women. Francis wrote a Rule for them which enforced poverty and made a will for Clara. The nuns supported themselves by the labor of their hands, but by Francis’ advice and example also became mendicants who depended on alms. Their rule was also modified in 1219 and the order was afterwards compelled to adopt the much older Benedictine rule.

The Tertiaries, or Brothers and Sisters of Penitence, were the third order of the Franciscans. The Tertiaries were lay brothers and sisters who held other employment but wanted to show a greater level of devotion to God than the common person. Francis never made an order for the Tertiaries. He simply called them to dedicate themselves wholly to God while going about their usual lives as merchants, workers and family men and women.

Francis wanted to include all classes of people, men and women, married and unmarried. His object was to put within the reach of lay-people the higher practice of virtue and godliness it was thought only sequestered monks or nuns could attain.

Historians wonder where Francis got his idea for his attempt to take the rigid formalism of the church of the Middle Ages back to more of a New Testament practice. Chances are good he took his example from the Waldenses, also called the Poor Men of Lyons, a group well known in Northern Italy in Francis’ day.

Most likely, it was Francis’ original intent to start an organic movement of lay-people, and that the idea of a monastic order only developed later.

Following Francis’ death, throughout the rest of the 13th C, the Franciscans were split into two groups; those who clung to his original vision and Rule and the stricter sect loyal to Cardinal Ugolino. The contest became so bitter that at times it fell to bloodshed. Eventually the pro-papal party prevailed.

In the pervious episode, I mentioned Francis was a bit of an anti-intellectual. That is to say, he’d seen too many priests who could parse fine points of doctrine, but who, like the religious leaders in the parable of the Good Samaritan, seemed not to understand the practical compassion, mercy and grace their theology ought to have stirred in them. Francis was not against learning per say; only when such study pre-empted living out what Truth commends. To a monastic leader named Anthony of Padua, Francis wrote, “I am agreed that you continue reading lectures on theology to the brethren provided that kind of study does not extinguish in them the spirit of humility and prayer.”

Francis’ followers departed from his anti-intellectual leaning and adopted the 13th Century’s trend of casting off the darkness of the Middle Ages by establishing schools and universities. They built schools in their convents and were well settled at the chief centers of university culture. In 1255, an order called upon Franciscans going out as missionaries to study Greek, Arabic, and Hebrew.

The order spread rapidly all the way to Israel and Syria in the East and Ireland in the West. It was introduced in France by Pacifico and Guichard, a brother-in-law of the French king. The first successful attempt to establish the order in Germany was made in 1221.

They took root in England in Canterbury and London in 1224. They were the first popular preachers England had seen, and the first to embody practical philanthropy. The condition of English villages and towns at that time was wretched. Skin diseases were common, including leprosy. Destructive epidemics spread rapidly due to the poor sanitation. The Franciscans chose quarters in the poorest and most neglected parts of towns. In Norwich, they settled in a swamp through which the city sewerage passed. At Newgate, now part of London, they settled into what was called Stinking Lane. At Cambridge, they occupied a decaying prison.

It was for this zeal to reach the poor and needy they received recognition. People soon learned to respect the brothers. By 1256, the number of English Franciscans had grown to over 1200, settled in just shy of fifty locations around England.

We’ll see what became of the Franciscans later. Suffice it to say, Francis would not approve of what became of his brotherhood. No he would NOT!

The Mendicant orders of the Franciscans and Dominicans, which we’ll look at next time, comprised a medieval poverty movement that was in large part, a reaction to the politicizing of the Faith. It was a movement of priests, monks and eventually commoners, who’d come to believe Church policies sought to wrangle political influence for ever more power in world affairs. These would-be reformers wondered, “Is this what Jesus and the Apostle intended? Didn’t Jesus say His Kingdom was NOT of this world? Why then are Bishops, Cardinals and Popes working so hard at controlling the political realm?”

The call to voluntary poverty drew its strength from widespread resentment of corrupt clergy; not that all or even most priests were. But it seemed the only priests selected for advancement were those who played the Church’s political game. The back-to-the-New Testament poverty movement of the Mendicants became a political movement in itself – a reform movement fueled by the spiritual hunger of the common people.

As early as the 10th C, reformers had called for a return to the poverty and simplicity of the early church. The life and example of the Apostles was regarded as the norm and when modern bishops were held up to that example, it was clear something unusual had happened; bishops in their religious finery stood markedly higher than the Apostles in terms of worldly power and wealth.

To illustrate this, visit the cathedral at Cologne, Germany. There’s a little museum there called the Treasury. It contains several display cases with the various vestments and tools the cardinals of Cologne have worn. Composed of gold and silver threads, encrusted with gems, these robes are priceless; literally. But one set of cases sums up for me the utter contradiction of an exalted clergy; the croziers. A crozier is a stylized shepherd’s staff carried by a bishop or cardinal. It’s a symbol of his role as a pastor, a shepherd. As a shepherd’s staff it ought to be a functional and useful tool. A humble piece of wood used to guide and protect sheep. But the croziers in the Treasury at Cologne Cathedral are made of solid gold, their head-pieces jammed with rubies, emeralds, diamonds, and pearls. You would no more use that to tend sheep than you would a painting by Rembrandt. Every time a cardinal wrapped his fingers around it, he ought to have been convicted deeply about how FAR FROM his calling as a humble servant to the flock we was.

Now, imagine you’re a commoner at church one Sunday. You’ve just been told by some priest God wants every bit of money you can give. How God NEEDS your money! Then in walks the Cardinal with his jewel-encrusted cape, his mitre and that priceless crozier in his hand.

How long before you begin to say to yourself, “WHAT is going on here? Did Jesus wear a get-up like that? Did Peter or John or any of the Apostles? I don’t think so. In fact, Jesus said something about not even having anywhere to lay his head. I’ll bet that Cardinal has a nice satin covered down pillow.”

In the earlier centuries of the Church, calls for reform were dealt with by channeling them into internal reform movements that directed attention away from the upper hierarchy to a more personal desire for reform that ended up in increased devotion. That’s what many of the monastic orders were. But by the 12th and 13th Centuries things began to change. Many of the lesser clergy began to speak out against the abuses of the Church. When they did they often entered the ranks of what were called “heretics.”

Francis adopted a radical devotion to poverty as a way to confront the blatant greed of the Church. His example spread like wild-fire precisely because it was so obvious to everyone how far off the Church had gotten. And it explains why Ugolino felt obligated to bring the order back in line by bringing it under the control of the Pope. While outwardly commending their order’s devotion to poverty, he installed policies that made the order dependent on their land holdings and property. It’s hard to criticize the wealth of “The Church,” when you’re part of that church and possess a good measure of that wealth.

Some were wise to Ugolino’s ways and went further by staying true to Francis’ original vision and commitment to poverty. Because they refused to knuckle under to his rule, they were declared heretical. And as heretics, they were treated with a brutality no one can reconcile with the Gospel of Grace. à But that, is for a later episode.

by Lance Ralston | Oct 19, 2014 | English |

This episode is titled – Monk Business Part 2

In the early 13th C a couple new monastic orders of preaching monks sprang up known as the Mendicants. They were the Franciscans and Dominicans.

The Franciscans were founded by Francis of Assisi. They concentrated on preaching to ordinary Christians, seeking to renew basic, Spirit-led discipleship. The mission of the Dominicans aimed at confronting heretics and aberrant ideas.

The Dominicans were approved by the Pope as an official, church sponsored movement in 1216, the Franciscans received Papal endorsement 7 years later.

They quickly gained the respect of scholars, princes, and popes, along with high regard by the masses. Their fine early reputation is counterbalanced by the idleness, ignorance, and in some cases, infamy, of their later history.

To be a Mendicant meant to rely on charity for support. A salary or wage isn’t paid by the church to support mendicant monks.

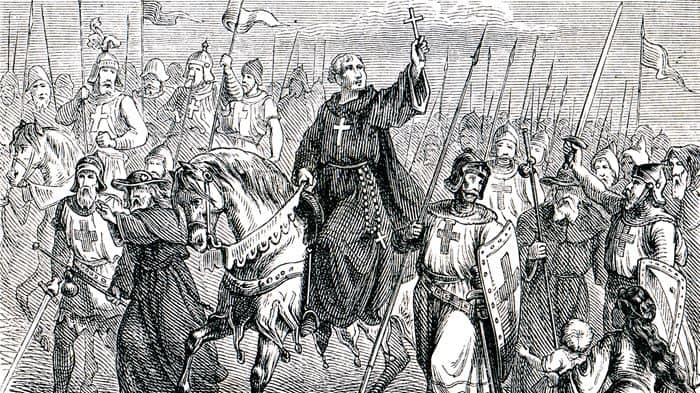

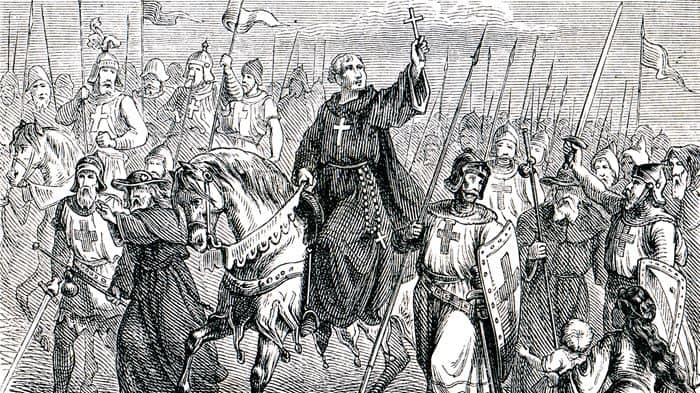

The appearance of these two mendicant orders was one of the most significant events of the Middle Ages, and marks one of the notable revivals in the history of the Christian Church. They were the Salvation Army of the 13th C. At a time when the spirit of the Crusades was waning and heresies threatened authority, Francis d’Assisi and Dominic de Guzman, an Italian and a Spaniard, united in reviving the spirit of the Western Church. They started monasticism on a new path. They embodied Christian philanthropy; the sociological reformers of their age. The orders they birthed supplied the new universities and study of theology with some of their most brilliant lights.

Two temperaments could scarcely have differed more widely than the temperaments of Francis and Dominic. The poet Dante described Francis as a Flame, igniting the world with love; Dominic he said, was a Light, illuminating the world.

Francis is the most unpretentious, gentle, and lovable of all greats of monastic life.

Dominic was, to put it bluntly à cold, systematic, and austere.

Francis was greater than the order that sought to embody his ways.

The Dominicans became greater than their master by taking his rules and building on them.

Francis was like one of the apostles; Dominic a later and lesser leader.

When you think of Francis, see him mingling with people or walking through a field, barefoot so his toes can feel the soil and grass. Dominic belongs in a study, surrounded by books, or in court pleading a case.

Francis’ lifework was to save souls. Dominic’s was to defend the Church. Francis has been celebrated for his humility and gentleness; Dominic was called the “Hammer of heretics.”

The two leaders probable met at least thre times. In 1217, they were both at Rome, and the Vatican proposed the union of the two orders into one organization. Dominic asked Francis for his cord, and bound himself with it, saying he desired the two to be one. A year later they again met at Francis’ church in Assisi, and on the basis of what he saw, Dominic decided to embrace mendicancy, which the Dominicans adopted in 1220. In 1221, Dominic and Francis again met at Rome, when a powerful Cardinal tried to wrest control of the orders.

Neither Francis nor Dominic wanted to reform existing monastic orders. At first, Francis had no intention of founding an order. He simply wanted to start a more organic movement of Christians to transform the world. Both Dominic and Francis sought to return the church to the simplicity and dynamic of Apostolic times.

Their orders differed from the older monastic orders in several ways.

First was their commitment to poverty. Dependence on charity was a primary commitment. Both forbade the possession of property. Not only did the individual monk pledge poverty, the entire order did as well. You may remember from our last episode this was a major turn-around from nearly all the previous monastic orders, who while the individual monks were pledged to poverty, their houses could become quite wealthy and plush.

The second feature was their devotion to practical activities in society. Previous monks had fled for solitude to the monastery. The Black and Gray Friars, as the Dominicans and Franciscans were called from the colors of their habits, gave themselves to the service of a needy world. To solitary contemplation they added immersion in the marketplace. Unlike some of the previous orders, they weren’t consumed with warring against their own flesh. They turned their attention to battling the effects of evil on the world. They preached to the common people. They relieved poverty. They listened to and sought to redress the complaints of the oppressed.

A third characteristic of the orders was that lay brotherhoods developed à a 3rd order, called the Tertiaries. These were lay men and women who, while pursuing their usual vocations, were bound by oath to practice the virtues of the Christian life.

Some Christians will hear this and say, “Wait – isn’t that what all genuine followers in Christ are supposed to do– follow Jesus obediently while being employed as a mechanic, student, salesman, engineer school-teacher or whatever?”

Indeed! But keep in mind that the doctrine of salvation by grace through faith, and living the Christian life by the power of the Spirit had been submerged under a lot of religion and ritual. It took the Reformation, three centuries later to clear away the ritualistic crust and restore the Gospel of Grace. In the 13th C, most people thought living a life that really pleased God meant being a monk, nun or priest. Lay brotherhood was a way for someone to in effect say – “My station in life doesn’t allow me to live a cloistered life; but if I could, I would.” Many, probably most believed they were hopelessly sinful, but that by giving to their priest or supporting the local monastery, the full-time religious guys could rack up a surplus of godliness they could draw on to cover them. The church facilitated this mindset. The message wasn’t explicit but implied was, “You go on and muddle through your helplessness, but if you support the church and her priests and monks, we’ll be able to pray for your sorry soul and do works of kindness God will bless, then we’ll extend our covering over you.”

On an aside, while that sounds absurd to many today, don’t in fact many repeat this? Don’t they fall to the same error when a husband hopes his believing wife is religious enough for the both of them? Or when a teenager assumes his family’s years of going to church will somehow reserve his/her spot in heaven? Salvation on the family-plan.

Lay brotherhood was a way for commoners to say, “Yeah, I don’t really buy that surrogate-holiness thing. I think God wants ME to follow Him and not trust someone else’s faith.”

A fourth feature was monks activity as teachers in the universities. They recognized these new centers of education held a powerful influence, and adapted themselves to the situation.

While the Dominicans were quick to enter the universities, the Franciscans lagged. They did so because Francis had resisted learning. He was a bit of an anti-intellectualist. He was because he’d seen way too much of the scholarship of priests who ignored the poor. So he said things like, “Knowledge puffs up, but charity edifies.”

To a novice he said, “If you have a songbook you’ll want a prayer-book; and if you have a prayer-book, you’ll sit on a high chair like a prelate, and say to your brother, ’Bring me my prayer-book.’ ” To another he said, “The time of tribulation will come when books will be useless and be thrown away.”

While this was Francis’ attitude toward academics, his successors among the Franciscans built schools and became sought after as professors in places like the University of Paris. The Dominicans led the way, and established themselves early at the seats of the two great continental universities, Paris and Bologna.

At Paris, Oxford, and Cologne, as well as a few other universities, they furnished the greatest of the Academics. Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, and Durandus, were Dominicans; John of St. Giles, Alexander Hales, Adam Marsh, Bonaventura, Duns Scotus, Ockham, and Roger Bacon were all Franciscans.

The fifth notable feature of the Mendicant orders was their quick approval by the Pope. The Franciscans and Dominicans were the first monastic bodies to vow allegiance directly to him. No bishop, abbot, or general chapter intervened between order and Pope. The two orders became his bodyguard and proved themselves to be a bulwark of the papacy. The Pope had never had such organized support before. They helped him establish his authority over bishops. Wherever they went, which was everywhere in Europe, they made it their business to establish the principle of the Vatican’s supremacy over princes and realms.

The Franciscans and Dominicans became the enforcement arm for doctrinal orthodoxy. They excelled all others in hunting down and rooting out heretics. In Southern France, they wiped out heresy with a river of blood. They were the leading instruments of the Inquisition. Torquemada was a Dominican. As early as 1232, Gregory IX officially authorized the Dominicans to carry out the Inquisition. And in a move that had to send Francis spinning at top speed in his burial plot, the Franciscans demanded the Pope grant them a share in the gruesome work. Under the lead of Duns Scotus they became champions of the doctrine of the immaculate conception of Mary.

The rapid growth of the orders in number and influence was accompanied by bitter rivalry. The disputes between them were so violent that in 1255 their generals had to call on their monks to stop fighting. Each order was constantly jealous that the other enjoyed more favor with the pope than itself.

It’s sad to see how quickly the humility of Francis and the desire for truth in Dominic was set aside by the orders they gave rise to. Because of the papal favor they enjoyed, monks of both orders began to intrude into every parish and church, incurring the hostility of the clergy whose rights they usurped. They began doing specifically priestly services, things monks were not authorized to do, like hearing confession, granting absolution, and serving Communion.

Though they’d begun as reform movements, they soon delayed reformation. They degenerated into obstinate obstructers of progress in theology and civilization. From being the advocates of learning, they became props to ignorance. The virtue of poverty was naught but a veneer for a vulgar and indolent insolence.

These changes set in long before the end of the 13th C, the same century the Franciscans and Dominicans had their birth. Bishops opposed them. The secular clergy complained of them. Universities ridiculed and denounced them for their mock piety and abundant vices. They were compared to the Pharisees and Scribes. They were declaimed as hypocrites that bishops were urged to purge from their dioceses. Cardinals and princes repeatedly appealed to popes to end their intrusions into church affairs, but usually the popes were on the Mendicant’s side.

In the 15th C, one well-known teacher listed the four great persecutors of the Church; tyrants, heretics, antichrist, and the Mendicants.

All of this is a sorry come-down from the lofty beginnings of their founders.

We’ll take the next couple episodes to go into a bit more depth on these two leaders and the orders they founded.

As we end this episode, I want to again say thanks to all those listeners and subscribers who’ve “liked” and left comments on the CS FB page.

I’d also like to say how appreciative I am to those who’ve gone to the iTunes subscription page for CS and left a positive review. Any donation to CS is appreciated.

by Lance Ralston | Oct 12, 2014 | English |

This 58th Episode of CS is titled – Monk Business Part 1 and is the first of several episodes in which we’ll take a look at monastic movements in Church History.

I realize that may not sound terribly exciting to some. The prospect of digging into this part of the story didn’t hold much interest for me either, until I realized how rich it is. You see, being a bit of a fan for the work of J. Edwin Orr, I love the history of revival. Well, it turns out each new monastic movement was often a fresh move of God’s Spirit in renewal. Several were a new wineskin for God’s work.

The roots of monasticism are worth taking some time to unpack. Let’s get started . . .

Leisure time to converse about philosophy with friends was prized in the ancient world. Even if someone didn’t have the intellectual chops to wax eloquent on philosophy, it was still fashionable to express a yearning for such intellectual leisure, or “otium” as it was called; but of course, they were much too busy serving their fellow man. It was the ancient version of, “I just don’t have any ‘Me-time’.”

Sometimes, as the famous Roman orator Cicero, the ancients did score the time for such reflection and enlightened discussion and retired to write on themes such as duty, friendship, and old age. That towering intellect and theologian, Augustine of Hippo had the same wish as a young man, and when he became a Christian in 386, left his professorship in oratory to devote his life to contemplation and writing. He retreated with a group of friends, his son and his mother, to a home on Lake Como, to discuss, then write about The Happy Life, Order and other such subjects, in which both classical philosophy and Christianity shared an interest. When he returned to his hometown in North Africa, he set up a community in which he and his friends could lead a monastic life, apart from the world, studying scripture and praying. Augustine’s contemporary, Jerome; translator of the Latin Bible known as the Vulgate, felt the same tug, and he, too, made a series of attempts to live apart from the world so he could give himself to philosophical reflection.

Ah; the Good Life!

This sense of a divine ‘call’ to a Christian version of this life of ‘philosophical retirement’ had an important difference from the older, pagan version. While reading and meditation remained central, the call to do it in concert with others who also set themselves apart from the world both spiritually and physically was added to the mix.

For the monks and nuns who sought such a communal life, the crucial thing was the call to a way of life which would make it possible to ‘go apart’ and spend time with God in prayer and worship. Prayer was the opus dei, the ‘work of God’.

As it was originally conceived, to become a monk or nun was to attempt to obey to the full the commandment to love God with all one is and has. In the Middle Ages, it was also understood to be a fulfillment of the command to love one’s neighbor, for monks and nuns prayed for the world. They really believed prayer was an important task on behalf of a morally and spiritually needy world of lost souls. So among the members of a monastery, there were those who prayed, those who ruled, and those who worked. The most important to society, were those who prayed.

A difference developed between the monastic movements in the East and West. In the East, the Desert Fathers set the pattern. They were hermits who adopted extreme forms of piety and asceticism. They were regarded as powerhouses of spiritual influence; authorities who could assist ordinary people with their problems. The Stylites, for example, lived on high platforms; sitting atop poles, and were an object of reverence to those who came to ask advice. Others, shut off from the world in caves or huts, sought to deny themselves any contact with the temptations of ‘the world’, especially women. There was in this an obvious preoccupation with the dangers of the flesh, which was partly a legacy of the Greek dualists’ conviction that matter and the physical world were unredeemably evil.

I pause to make a personal, pastoral observation. So warning! – Blatant opinion follows.

You can’t read the NT without seeing the call to holiness in the Christian Life. But that holiness is a work of God’s grace as the Holy Spirit empowers the believer to live a life pleasing to God. NT holiness is a joyous privilege, not a heavy burden and duty. NT holiness enhances life, never diminishes it.

This is what Jesus modeled so well; and it’s why genuine seekers after God were drawn to him. He was attractive. He didn’t just do holiness, He WAS Holy. Yet no one had more life. And everywhere He went, dead things came to life!

As Jesus’ followers, we’re supposed to be holy in the same way. But if we’re honest, we’d have to admit that for the vast majority, holiness is conceived as a dry, boring, life-sucking burden of moral perfection.

Real holiness isn’t religious rule-keeping. It isn’t a list of moral proscriptions; a set of “Don’t’s! Or I will smite thee with Divine Wrath and cast thy wretched soul into the eternal flames!”

NT holiness is a mark of Real Life, the one Jesus rose again to give us. It’s Jesus living in and thru us.

The Desert Fathers and hermits who followed their example were heavily influenced by the dualist Greek worldview that all matter was evil and only the spirit was good. Holiness meant an attempt to avoid any shred of physical pleasure while retreating into the life of the mind. This thinking was the major force influencing the monastic movement as it moved both East and West. But in the East, the monks were hermits who pursued their lifestyles in isolation while in the West, they tended to pursue them in concert and communal life.

As we go on we’ll see that some monastic leaders realized casting holiness as a negative denial of the flesh rather than a positive embracing of the love and truth of Christ was an error they sought to reform.

In the East, while monks might live in a group, they didn’t seek for community. They didn’t converse or work together in a common cause. They simply shared cells next to one another. And each followed his own schedule. Their only real contact was that they ate together and might pray together. This tradition continues to this day on Mount Athos in northern Greece, where monks live in solitude and prayer in cells high on the cliffs, food lowered to them in baskets.

A crucial development in Western monasticism took place in the 6th C, when Benedict of Nursia withdrew with a group of friends to live an ascetic life. This prompted him to give serious thought to the way in which the ‘religious life’ should be organized. Benedict arranged for groups of 12 monks to live together in small communities. Then he moved to Monte Cassino where, in 529, he set up the monastery which was to become the mother house of the Benedictine Order. The rule of life he drew up there was a synthesis of elements in existing rules for monastic life. From this point on, the Rule of St Benedict set the standard for living the religious life until the 12th C.

The Rule achieved a good working balance between the body and soul. It aimed at moderation and order. It said that those who went apart from the world to live lives dedicated to God should not subject themselves to extreme asceticism. They should live in poverty and chastity, and in obedience to their abbot, but they shouldn’t feel the need to brutalize their flesh with things like scourges and hair-shirts. They should eat moderately but not starve. They should balance their time in a regular and orderly way between manual work, reading and prayer—their real work for God. There were to be seven regular acts of worship in the day, known as ‘hours’, attended by the entire community. In Benedict’s vision, the monastic yoke was to be sweet; the burden light. The monastery was a ‘school’ of the Lord’s service, in which the baptized soul made progress in the Christian life.

In the Anglo-Saxon period of English history, nuns formed a significant part of the population. There were several ‘double monasteries’, where communities of monks and nuns lived side by side. Several female abbots, called ‘abbesses’ proved to be outstanding leaders. Hilda, the Abbess of the double monastery at Whitby played a major role at the Synod of Whitby in 664.

A common feature of monastic life in the West was that it was largely reserved for the upper classes. Serfs generally didn’t have the freedom to become monks. The houses of monks and nuns were the recipients of noble and royal patronage, usually because the nobility thought by supporting such a holy endeavor, they promoted their spiritual case with God. Remember as well that while the first-born son stood to inherit everything, later sons were a potential cause of unrest if they decided to vie with their elder brother in gaining the birthright. So these ‘spare’ children of good birth were often given to monastic communes by their families. They were then charged with carrying the religious duty for the entire family. They were a kind of “spiritual surrogate” whose task was to produce a surplus of godliness the rest of the family could draw from. Rich and powerful families gave monasteries, lands and estates, for the good of the souls of their members. Rulers and soldiers were too busy to attend to their spiritual lives, so ‘professionals’ drawn from their own families could help them by doing it on their behalf.

A consequence of this was that, in the late Middle Ages, the abbot or abbess was usually a nobleman or woman. She/He was often chosen because of being the highest in birth in the monastery or convent, and not because of any natural powers of leadership or outstanding spirituality. Chaucer’s cruel 14th C caricature of a prioress depicts a woman who would have been much more at home in a country house playing with her pet dogs.

In these features of noble patronage of the religious life lay not only the stamp of society’s approval, but also the potential for decay. Monastic houses that became rich and were filled with those who’d not chosen to enter the religious life, but had been put there in childhood, often became decadent. The Cluniac reforms of the 10th C were a consequence of the recognition that there would need to be a tightening of the ship if the Benedictine order was not to be lost altogether. In the commune at Cluny and the houses which imitated it, standards were high, although here, too, there was a danger of distortion of the original Benedictine vision. Cluniac houses had extra rules and a degree of rigidity which compromised the original simplicity of Benedictine life.

At the end of the 11th C, several developments radically altered the range of choice for those in the West who wanted to enter a monastery. The first was a change of fashion, which encouraged married couples of mature years to decide to end their days as a monk or nun. A knight who’d fought his wars might make an agreement with his wife that they would go off into separate religious houses. Adult entry of this sort was by those who really did want to be there, and it had the potential to alter the balance in favor of serious commitment.

But these mature adults weren’t the only one’s entering monasteries. It became fashionable for younger people to head off to a monastery where education had become top-rank. Then monasteries began to specialize in various pursuits. It was a time of experimentation.

Out of this period of experiment came one immensely important new order, the Cistercians. They used the Benedictine rule, but had a different set of priorities. The first was a determination to protect themselves from the dangers which could come from growing too rich.

“Too rich?” you might ask. “How’s that possible if they’d taken a vow of poverty?”

Ah à There’s the rub.

Yes; monks and nuns vowed poverty, but their lifestyle included diligence in work. And some brilliant minds had joined the monasteries, so they’d devised ingenious methods for going about their work in a more productive manner, enhancing yields of crops and products. Being deft businessmen, they worked good deals and maximized profits, which went in to the monastery’s account. But individual monks, of course, didn’t profit thereby. The funds were used to expand the monastery’s resources and facilities. This led to even higher profits. Which were then used in plushing up the monastery itself. The monks’ cells got nicer, the food better, the grounds more sumptuous, the library more expansive. The monks got new outfits. Outwardly things technically were the same, they owned nothing personally, but in fact, their monastic world was upgraded significantly.

The Cistercians responded to this by building houses in remote places and keeping them as simple, bare lodgings. They also made a place for people from the lower social classes who had vocations but wanted to give themselves more completely to God for a period of time. These were called “lay brothers.”

The rather startling early success of the Cistercians was due to Bernard of Clairvaux. When he decided to enter a newly founded Cistercian monastery, he took with him a group of friends and relatives. Because of his oratory skill and praise for the Cistercian model, recruitment proceed so rapidly many more houses had to be founded in quick succession. He was made abbot of one of them at Clairvaux, from which he draws his name. He went on to become a leading figure in the monastic world and in politics. He spoke so well and so movingly that he was useful as a diplomatic emissary, as well as a preacher. You may remember he was one of the premier reasons the Crusades were able to rally so many to their campaign.

Other monastic experiments weren’t so successful. The willingness to try new forms of the monastic life gave a platform for some short-lived endeavors by the eccentric. There are always those who think their idea is THE way it ought to be done. Either because they lack common sense or have no skill at recruiting, they fall apart. So many were engaged in pushing forward the boundaries of monastic life one writer thought it would be helpful to review the available modes in the 12th C. His work covered all the possibilities, from the Benedictines and reformed Benedictines, to priests who didn’t live enclosed lives, but who were allowed to work in the world—and the various sorts of hermits.

The only real rival to the Rule of St Benedict was the ‘Rule’ of Augustine, which was adopted by church leaders. These differed from monks, in that they were priests who could be active in the wider social community, for example, by serving in a parish church. They weren’t living under a monastic rule which confined a monk for life to the house in which he was consecrated. Priests serving in a cathedral, for example, were encouraged to live in a city but under a code like the Augustinian rule which was well-adapted to their needs.

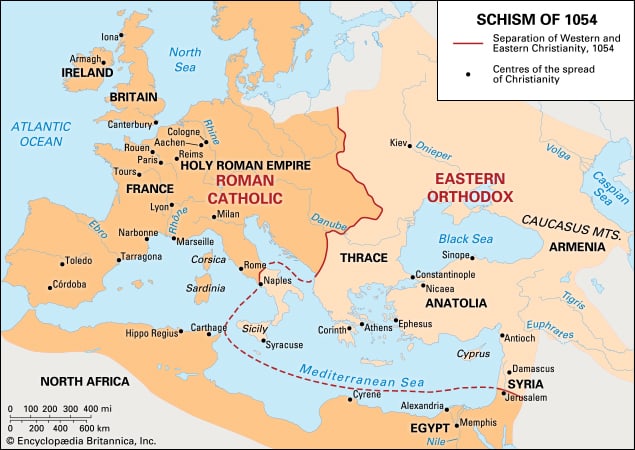

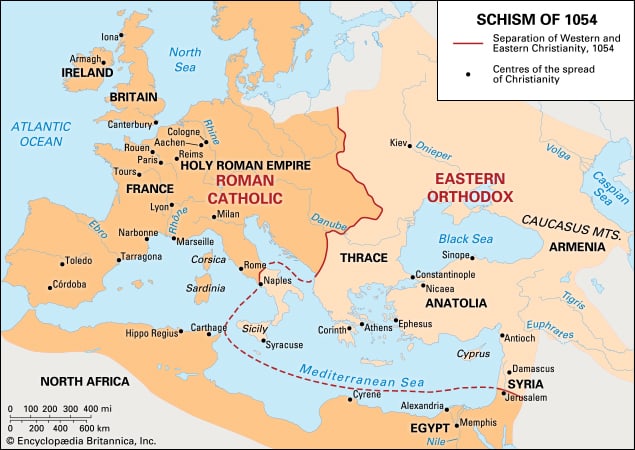

The 12th C saw the creation of new monastic orders. In Paris, the Victorines produced leading academic figures and teachers. The Premonstratensians were a group of Latin monks who took on the massive task of healing the rift between the Eastern and Western churches. The problem was, there was no corresponding monastic group in the East.

We’ll pick it up at this point next time.

Monasticism is an important part of Church History because of the huge impact it had shaping the faith of common Christians throughout the Middle Ages and on into the Renaissance. Some of the monastic leaders are the great pillars of the faith. We can’t really understand them without knowing a little about the world they lived in.

As we end this episode, I want to again say thanks to all those listeners and subscribers who’ve “liked” and left comments on the CS FB page.

I’d also like to say how appreciative I am to those who’ve gone to the iTunes subscription page for CS and left a positive review. We’ve developed a large listener base.

Any donation to CS is appreciated.

Finally, for interested subscribers, I want to invite you to take a listen to the sermon podcast for the church I serve; Calvary Chapel Oxnard. I teach expositionally through the Bible. You can subscribe via iTunes, just do a search for Calvary Chapel Oxnard podcast, or link to the calvaryoxnard.org website.

by Lance Ralston | Oct 5, 2014 | English |

This is part 4 of our series on the Crusades.

The plan for this episode, the last in our look at the Crusades, is to give a brief review of the 5th thru 7th Crusades, then a bit of analysis of the Crusades as a whole.

The date set for the start of the 5th Crusade was June 1st, 1217. It was Pope Innocent III’s long dream to reconquer Jerusalem. He died before the Crusade set off, but his successor Honorius III was just as ardent a supporter. He continued the work begun by Innocent.

The Armies sent out accomplished much of nothing, except to waste lives. Someone came up with the brilliant idea that the key to conquering Palestine was to secure a base in Egypt first. That had been the plan for the 4th Crusade. The Crusaders now made the major port of Damietta their goal. After a long battle, the Crusaders took the city, for which the Muslim leader Malik al Kameel offered to trade Jerusalem and all Christian prisoners he held. The Crusaders thought the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II was on his way to bolster their numbers, so they rejected the offer. Problem is, Frederick wasn’t on his way. So in 1221, Damietta reverted to Muslim control.

Frederick II cared little about the Crusade. After several false starts that revealed his true attitude toward the whole thing, the Emperor decided he’d better make good on his many promises and set out with 40 galleys and only 600 knights. They arrived in Acre in early Sept. 1228. Because the Muslim leaders of the Middle East were once again at odds with each other, Frederick convinced the afore-mentioned al-Kameel to make a decade long treaty that turned Jerusalem over to the Crusaders, along with Bethlehem, Nazareth, and the pilgrim route from Acre to Jerusalem. On March 19, 1229, Frederick crowned himself by his own hand in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

This bloodless assumption of Jerusalem infuriated Pope Gregory IX who considered control of the Holy Land and the destruction of the Muslims as one and the same thing. So the Church never officially acknowledged Frederick’s accomplishments.

He returned home to deal with internal challenges to his rule and over the next decade and a half, the condition of Palestine’s Christians deteriorated. Everything gained by the treaty was turned back to Muslim hegemony in the Fall of 1244.

The last 2 Crusades, the 6th and 7th, center on the career of the last great Crusader; the king of France, Louis IX.

Known as SAINT Louis, he combined the piety of a monk with the chivalry of a knight, and stands in the front rank of all-time Christian rulers. His zeal revealed itself not only in his devotion to religious ritual, but in his refusal to deviate from his faith even under the threat of torture. His piety was genuine as evidenced by his concern for the poor and the just treatment of his subjects. He washed the feet of beggars and when a monk warned him against carrying his humility too far, he replied, “If I spent twice as much time in gambling and hunting as in such services, no one would find fault with me.”

The sack of Jerusalem by the Muslims in 1244 was followed by the fall of the Crusader bases in Gaza and Ashkelon. In 1245 at the Council of Lyons the Pope called for a new expedition to once again liberate the Holy Land. Though King Louis lay in a sickbed with an illness so grave his attendants put a cloth over his face, thinking he was dead, he rallied and took up the Crusader cross.

Three years later he and his French brother-princes set out with 32,000 troops. A Venetian and Genoese fleet carried them to Cyprus, where large-scale preparations had been made for their supply. They then sailed to Egypt. Damietta once again fell, but after this promising start, the campaign turned into a disaster.

Louis’ piety and benevolence was not backed up by what we might call solid skills as a leader. He was ready to share suffering with his troops but didn’t possess the ability to organize them. Heeding the counsel of several of his commanders, he decided to attack Cairo instead of Alexandria, the far more strategic goal. The campaign was a disaster with the Nile being chocked with bodies of slain Crusaders. On their retreat, the King and Count of Poitiers were taken prisoners. The Count of Artois was killed. The humiliation of the Crusaders had rarely been so deep.

Louis’ fortitude shone brightly while suffering the misfortune of being held captive. Threatened with torture and death, he refused to renounce Christ or yield up any of the remaining Crusader outposts in Palestine. For the ransom of his troops, he agreed to pay 500,000 livres, and for his own freedom to give up Damietta and abandon the campaign in Egypt.