by Lance Ralston | Aug 10, 2014 | English |

The title of this episode is “What a Mess!”

As is often the case, we start by backing up & reviewing material we’ve already covered so we can launch into the next leg of our journey in Church History.

Anglo-Saxon missionaries to Germany had received the support of Charles Martel, a founder of the Carolingian dynasty. Martel supported these missions because of his desire to expand his rule eastwards into Bavaria. The Pope was grateful for his support, and for Charles’ victory over the Muslims at the Battle of Tours. But Martel fell afoul of papal favor when he confiscated Church lands. At first, the Church consented to his seizing of property to produce income to stave off the Muslim threat. But once that threat was dealt with, he refused to return the lands. Adding insult to injury, Martel ignored the Pope’s request for help against the Lombards taking control of a good chunk of Italy. Martel denied assistance because at that time the Lombards were his allies. But a new era began with the reign of Martel’s heir, Pippin or as he’s better known, Pepin III.

Pepin was raised in the monastery of St. Denis near Paris. He & his brother were helped by the church leader Boniface to carry out a major reform of the Frank church. These reforms of the clergy and church organization brought about a renewal of religious and intellectual life and made possible the educational revival associated with the greatest of the Carolingian rulers, Charlemagne & his Renaissance.

In 751, Pepin persuaded Pope Zachary to allow Boniface to anoint him, King of the Franks, supplanting the Merovingian dynasty. Then, another milestone in church-state relations passed with Pope Stephen II appealing to Pepin for aid against the Lombards. The pope placed Rome under the protection of Pepin and recognized him and his sons as “Protectors of the Romans.”

As we’ve recently seen, all of this Church-State alliance came to a focal point with the crowning of Charlemagne as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in AD 800. For some time the Popes in Rome had been looking for a way to loosen their ties to the Eastern Empire & Constantinople. Religious developments in the East provided the Popes an opportunity to finally break free. The Iconoclastic Controversy dominating Eastern affairs gave the Popes one more thing to express their disaffection with. We’ll take a closer look at the controversy later. For now, it’s enough to say the Eastern Emperor Leo III banned the use of icons as images of religious devotion in AD 726. The supporters of icons ultimately prevailed but only after a century of bitter and at times violent dispute. Pope Gregory II rejected Leo’s edict banning icons and flaunted his disrespect for the Emperor’s authority. Gregory’s pompous and scathing letter to the Emperor was long on bluff but a dramatic statement of his rejection of secular rulers’ meddling in Church affairs. Pope Gregory wrote: “Listen! Dogmas are not the business of emperors but of pontiffs.”

The reign of what was regarded by the West as a heretical dynasty in the East gave the Pope the excuse he needed to separate from the East and find a new, devoted and orthodox protector. The alliance between the papacy and the Carolingians represents the culmination of that quest, and opened a new and momentous chapter in the history of European medieval Christianity.

In response to Pope Stephen’s appeal for help against the Lombards, Pepin recovered the Church’s territories in Italy and gave them to the pope, an action known as the ‘Donation of Pepin’. This confirmed the legal status of the Papal States.

At about the same time, the Pope’s claim to the rule of Italy and independence from the Eastern Roman Empire was reinforced by the appearance of one of the great forgeries of the Middle Ages, the Donation of Constantine. This spurious document claimed Constantine the Great had given Rome and the western part of the Empire to the bishop of Rome when he moved the capital of the empire to the East. The Donation was not exposed as a forgery until the 15th Century.

The concluding act in the popes’ attempt to free themselves from Constantinople came on Christmas Day 800 when Pope Leo III revived the Empire in the West by crowning Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor. It’s rather humorous, as one wag put it – the Holy Roman Empire was neither Holy, nor Roman, and can scarcely be called an Empire.

Charlemagne’s chief scholar was the British-born Alcuin who’d been master of the cathedral school in York. He was courted by Charlemagne to make his capital at Aachen on the border between France & Germany, Europe’s new center of education & scholarship. Alcuin did just that. If the school at Aachen didn’t plant the seeds that would later flower in the Renaissance it certainly prepared the soil for them.

Alcuin profoundly influenced the intellectual, cultural and religious direction of the Carolingian Empire, as the 300-some extant letters he wrote reveal. His influence is best seen in the manuscripts of the school at Tours where he later became abbot. His influence is also demonstrated in his educational writings, revision of the Biblical text, commentaries and the completion of his version of Church liturgy. He standardized spelling and writing, reformed missionary practice, and contributed to the organizing of church regulations. Alcuin was the leading theologian in the struggle against the heresy of Adoptionism. Adoptionists said Jesus was simply a human being who God adopted & MADE a Son. Alcuin was a staunch defender of Christian orthodoxy and the authority of the Church, the pre-eminence of the Roman Bishop and of Charlemagne’s sacred position as Emperor. He died in 804.

The time at which Alcuin lived certainly needed the reforms he brought & he was the perfect agent to bring them. From the palace school at Aachen, a generation of his students went out to head monastic and cathedral schools throughout the land. Even though Charlemagne’s Empire barely outlived its founder, the revival of education and religion associated with he and Alcuin brightened European culture throughout the bleak and chaotic period that followed. This Carolingian Renaissance turned to classical antiquity and early Christianity for its models. The problem is, there was only one Western scholar who still knew Greek, the Irishman John Scotus Erigena. Still, the manuscripts produced during this era form the base from which modern historians gain a picture of the past. It was these classical texts, translated from Greek into Latin that fueled the later European Renaissance.

The intellectual vigor stimulated by the Carolingian Renaissance and the political dynamism of the revived Empire stimulated new theological activity. There was discussion about the continuing Iconoclastic problem in the East. Political antagonism between the Eastern and the Carolingian emperors led to an attack by theologians in the West on the practices and beliefs of the Orthodox Church in the East. These controversial works on the ‘Errors of the Greeks’ flourished during the 9th C as a result of the Photian Schism.

In 858, Byzantine Emperor Michael III deposed the Patriarch Ignatius I of Constantinople, replacing him with a lay scholar named Photius I, AKA Photius the Great. The now deposed Ignatius appealed to Pope Nicholas I to restore him while Photius asked the Pope to recognize his appointment. The Pope ordered the restoration of Ignatius & relations between East & West sunk further. The issue ended in 867 when Pope Nicholas died & Photius was deposed.

Latin theologians also criticized the Eastern church for its different method of deciding the date of Easter, the difference in the way clergy cut their hair, and the celibacy of priests. The Eastern Church allowed priests to marry while requiring monks to be celibate, whereas the Western Church required celibacy of both.

Another major doctrinal debate was the Filioque [Filly-o-quay] Controversy we briefly touched on in an earlier episode. Now, before I get a barrage of emails, there’s debate among scholars over the pronunciation of Filioque. Some say “Filly-oak” others “Filly-o-quay.” Take your pick.

The point is, the Controversy dealt with the wording of the Nicene Creed as related to the Holy Spirit. The original Creed said the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father. A bit later, the Western Church altered the wording a bit so as to affirm the equality of the Son of God with the Father. So they said the Spirit proceeded from both Father & Son. Filioque is Latin for “and the Son” thus giving the name of the controversy. The Eastern Church saw this addition as dangerous tampering with the Creed and refused to accept it while the Filioque clause became a standard part of what was considered normative doctrine in the West.

Another major discussion arose over the question of predestination. A Carolingian monk named Gottschalk, who studied Augustine’s theology carefully, was the first to teach ‘double predestination’; the belief that some people are predestined to salvation, while others are predestined to damnation. He was tried and condemned for his views by 2 synods and finally imprisoned by the Archbishop of Rheims. Gottschalk died 20 years later, holding his views to the end.

The other major theological issue of the Carolingian era concerned the Lord’s Supper. The influential Abbot of Corbie wrote a treatise titled On the Body and Blood of the Lord. This was the first clear statement of a doctrine of the ‘real presence’ of Christ’s body and blood in the Communion elements, later called the doctrine of “transubstantiation,” an issue that will become a heated point in the debate between the Roman Church & Reformers.

The reforms of King Pepin and Pope Boniface focused attention on priests. It was clear to all that clergy ought to lead lives beyond reproach. That synod after synod during the 6th, 7th, & 8th Cs had to make such a major issue of this demonstrated the need for reform. Among the violations warned against were the rejection of celibacy, gluttony, drunkenness, tawdry relationships with women, hunting, carrying arms & frequenting taverns.

Monastic developments at this time were significant. The emphasis was on standardization and centralization. Between 813 and 17 a revised Benedictine rule was adopted for the whole of the Carolingian Empire. Another Benedict, a monk from Burgundy, was responsible for an ultra-strict regimen. Charlemagne’s successor, Louis the Pious, appointed Benedict the overseer of all monasteries in the realm, and a few years later his revised Benedictine rule was made obligatory for all monasteries. Sadly, with little long-term effect.

When Louis succeeded Charlemagne, the Pope was able to regain his independence, following a long domination by the Emperor. The imperial theocracy of Charlemagne’s reign would have yielded a ‘state church’ as already existed in the East. But the papacy stressed the superiority of spiritual power over the secular. This was reinforced by the forged Donation of Constantine with its emphasis on papal pre-eminence in the governing of the Empire, not just the Church.

In the middle of the 9th C, priests at Rheims produced another remarkable forgery, the False Decretals. Accomplished with great inventiveness, the Decretals were designed to provide a basis in law which protected the rights of bishops. They included the bogus Donation of Constantine and became a central part of the canon of medieval law. It shored up papal claims to supremacy in church affairs over secular authority. The first Pope to make use of the False Decretals was Nicholas I. He recognized the danger of a Church dominated by civil rulers and was determined to avert this by stressing that the church’s government was centered on Rome, not Constantinople, and certainly not in some lesser city like Milan or Ravenna.

From the late 9th until the mid-11th C, Western Christendom was beset by a host of major challenges that left the region vulnerable. The Carolingian Empire fragmented, leaving no major military power to defend Western Europe. Continued attacks by Muslims in the S, a fresh wave of attacks by the Magyars in the E, and incessant raids by the Norsemen all over the Empire, turned the shards of the empire into splinters. One contemporary lamented, “Once we had a king, now we have kinglets!” For many Western Europeans, it seemed the end of the world was at hand.

The popes no longer had Carolingian rulers as protectors. So the papacy became increasingly involved in the power struggles among the nobility for the rule of Italy. Popes became partisans of one political faction or another; sometimes willingly, other times coerced. But the cumulative result was spiritual and moral decline. For instance, Pope Stephen VI took vengeance on the preceding pope by having his body disinterred and brought before a synod, where it was propped up in a chair for trial. Following conviction, the body was thrown into the Tiber River. Then, within a year Stephen himself was overthrown. He was strangled while in prison.

There was a near-complete collapse of civil order in Europe during the 10th C. Church property was ransacked by invaders or fell into the hands of the nobility. Noblemen treated churches and monasteries as their private property to dispose of as they wished. The clergy became indifferent to duty. Their illiteracy & immorality grew.

The 10th C was a genuine dark age, at least as far as the condition of the Church was concerned. Without imperial protection, popes became helpless playthings for the nobility, who fought to gain control by appointing relatives and political favorites. A chronicle by the German bishop of Cremona paints a graphic picture of sexual debauchery in the Church.

Though there were incompetent & immoral popes during this time, they continued to be respected throughout the West. Bishoprics and abbeys were founded by laymen after they obtained the approval of the papal court. Pilgrimages to Rome hardly slackened during this age, as Christians visited the sacred sites of the West; that is, the tombs of Peter and Paul, as well as a host of other relics venerated in there.

At the lowest ebb of the 10th C, during the reign of Pope John XII, from 955-64, a major change in Italian politics affected the papacy. An independent & capable German monarchy emerged. This Saxon dynasty began with the election of Henry I and continued with his son, Otto I, AKA Otto the Great .

Otto developed a close relationship with the Church in Germany. Bishops and abbots were given the rights and honor of high nobility. The church received huge tracts of land. Thru this alliance with the Church, Otto aimed to forestall the rebellious nobles of his kingdom.

But the new spiritual aristocracy created by Otto wasn’t hereditary. Bishops & abbots couldn’t “pass on” their privileges to their successors. Favor was granted by the King to whomever he chose. Thus, their loyalty could be counted on more readily. In fact, the German bishops contributed money and arms to help the German kings expand into Italy, what is now the regions of East Germany & Poland.

Otto helped raise the papacy out of the quagmire of Italian politics. His entrance into Italian affairs was a fateful decision. He marched south into Italy to marry Adelaide of Burgundy and declare himself king of the Lombards. Ten years later, he again marched south at the invitation of Pope John XII. In February of 962, the Pope tried a renewal of the Holy Roman Empire by crowning Otto and Adelaide in St Peter’s. But the price paid by the pope for Otto’s support was another round of interference in Church affairs.

For the next 300 years, each new German monarch followed up his election by making a march to Rome to be crowned as Emperor. But at this point, it wasn’t so much Popes who made Emperors as it was Emperors who made Popes. And when a pope ran afoul of the ruler, he was conveniently labeled ‘anti-pope’ & deposed, to be replaced by the next guy. It was the age of musical chairs in Rome; whoever grabs the papal chair when the music stops gets to sit. But when the Emperor instructs the band to play again, whoever’s in the chair has to stand and the game starts all over again. Lest you think I’m overstating the case, in 963 Otto returned to Rome, convened a synod which found Pope John guilty of a list of sordid crimes and deposed him. In his place, they chose a layman, who received all of his ecclesiastical orders in a single day to become Pope Leo VIII. He managed to sit in the Pope’s chair less than a year before the music started all over again.

by Lance Ralston | Aug 3, 2014 | English |

Welcome to the 49th installment of CS. This episode is titled “Charlemagne Pt. 2.”

After his coronation on Christmas Day AD 800, Charlemagne said he didn’t know it had been planned by Pope Leo III. If setting the crown of a new Holy Roman Empire on his head was a surprise, he got over the shock right quick. He quickly shot off dispatches to the lands under his control to inform them he was large and in-charge. Each missive began with these words, “Charles, by the will of God, Roman Emperor, Augustus … in the year of our consulship 1.” He required an oath be taken to him as Caesar by all officers, whether religious or civil. He sent ambassadors to soothe the inevitable wrath of the Emperor in Constantinople.

What’s important to note is how his coronation ceremony in St. Peter’s demonstrated the still keen memory of the Roman Empire that survived in Europe. His quick emergence as the recognized leader of a large part of Europe revealed the strong desire there was to reestablish a political unity that had been absent from the region for 400 years. But, Charlemagne’s coronation launched a long-standing contest. One we’d not expect, since it was, after all, the Pope who crowned him. The contest was between the revived empire and the Roman Church.

In the medieval world, Church and State were two realms comprising Christendom. The Medieval Church represented Christian society aimed at acquiring spiritual blessings, while the Medieval State existed to safeguard civil justice and tranquility. Under the medieval system, both Church and State were supposed to exist side by side in a harmonious relationship, each focused on gaining the good of mankind but in different spheres; the spiritual and the civil.

In reality, it rarely worked that way. The Pope and Emperor were usually contestants in a game of thrones. The abiding question was: Does the Church rule the State, or the State the Church? This contest was played out on countless fields, large and small, throughout the Middle Ages.

Charlemagne left no doubt about where sovereignty lay during His reign. He provided Europe a colossal father figure as the first Holy Roman Emperor. Everyone was answerable to him. To solve the problem of supervising local officials in his expansive realm, Charlemagne passed an ordinance creating the missi dominici or king’s envoys. These were pairs of officials, a bishop and noble, who traveled the realm to check on local officials. Even the pope was kept under the watchful imperial eye.

Though Charlemagne occasionally used the title “emperor” in official documents, he usually declined it because it appeared to register his acceptance of what the Pope had done at his coronation. Charlemagne found this dangerous; that the Pope was now in a position to make an Emperor. The concern was—The one who can MAKE an emperor, can un-make him. Charles thought it ought to be the other way around; that Emperors selected and sanctioned Popes.

In truth, what Pope Leo III did on Christmas Day of 800 when he placed the crown on Charlemagne’s head was just a final flourish of what was already a well-established fact – Charles was King of the Franks. One recent lecturer described the coronation as the cherry on the top of a sundae that had already been made by Charles the Great.

In our last episode we saw a major objective of Charlemagne’s vision was to make Europe an intellectual center. He launched a revival of learning and the arts. Historians speak of this as the Carolingian Renaissance. Charlemagne required monasteries to have a school for the education of boys in grammar, math and singing. At his capital of Aachen he built a school for the education of the royal court. The famous English scholar Alcuin headed the school, and began the difficult task of reviving learning in the early Middle Ages by authoring the first textbooks in grammar, rhetoric, and logic.

It was Charlemagne’s emphasis on education that proved to be his enduring legacy to history. He sent out agents far and wide to secure every work of the classical age they could find. They returned to Aachen and the monastery schools where they were translated into Latin. This is why Latin became the language of scholarship in the ages to come. It was helped along by Charlemagne’s insistence a standard script be developed – Carolingian miniscule. Now, scholars all across Western Europe could read the same materials, because a consistent script was being used for Latin letters.

This became one of the most important elements in making the Renaissance possible.

Few historians deny Charlemagne’s massive impact on European history, and thereby, the history of the modern world. The center of western civilization shifted from the Mediterranean to Northern Europe. After 300 years of virtual chaos, Charles the Great restored a measure of law and order. His sponsorship of the intellectual arts laid a heritage of culture for future generations. And the imperial ideal he revived persisted as a political force in Europe until 1806, when the Holy Roman Empire was terminated by another self-styled emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte.

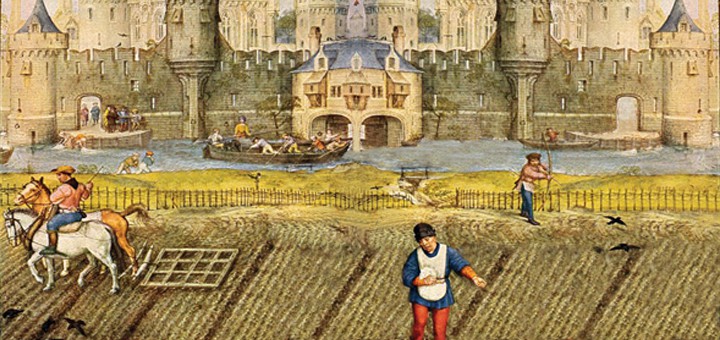

In reality, the peace of Charlemagne’s rule was short-lived. His empire were too vast, its nobility too powerful to be held together once his domineering personality was removed. Like Clovis before him, Charlemagne’s successors were weak and the empire disintegrated into a confusion of civil wars and new invasions. The Northmen began their incessant raiding forays, called going “a-viking” à So we know them as the Vikings. They set sail from Scandinavia in their shallow-hulled long ships, able to sail up rivers and deep inland, where they raided villages, towns and any other unfortunate hamlet they came on. These raids of the Vikings, forced the native peoples to surrender, first their lands, then their persons to the counts, dukes, and other local lords who began to multiply during this time, in return for protection from the raiders. It’s not difficult to see how the process of feudalism developed.

Common people needed protection from raiders; whoever they were. But the king and his army was a long way away. It could take weeks, months even, to send a message and get help in reply. In the meantime, the Vikings are right here; right now. See ‘em? Yeah à That blond, long-haired giant berserker with his 2 headed battle axe is about to crash through my door. What good is the king and his army in Aachen or Paris?

What I need is someone near with enough men at his call, enough trained and armed soldiers that is, who can turn away a long-ship’s crew of 50 berserkers. How expensive is it to hire, train, outfit and keep a group of soldiers; figure 2 for ever Viking? Who can field an army of a hundred professional soldiers? Well, the nearest Count is 20 minutes away and he only has a half dozen hired men for protection.

That count’s a smart guy though and realizes he’s the only one in the area to do what needs to be done. So he goes to 25 of the area’s farmers and says, “Listen, I’ll protect you. But to do that, I need to field an army of a hundred men. That’s very expensive to do so here’s what I need in exchange for protection: Give me the title to your land. You live on and continue to work it. You keep half the yield of all the farm produces; the rest is mine. And for that, I and my army will keep you safe.”

When the choice is either yield to that Count or face the long-ships on your own; there’s not much choice. So feudalism with its system of serfs, counts, barons, dukes, and earls began.

Central to feudalism was the personal bond between lord and vassals. In the ceremony known as the act of homage, the vassal knelt before his lord, and promised to be his “man.” In the oath of loyalty that followed, called fealty, the vassal swore on a Bible, or a sacred object such as a Cross. Then, in the ritual of investiture, a spear, a glove, or a bit of straw was handed to the vassal to signify his control, but not ownership, over his allotted piece of the lord’s realm.

The feudal contract between lord and vassal was sacred and binding on both parties. Breaking the tie was a major felony because it was the basic bond of medieval society. It was thought that to break the rules of feudal society was to imperil all of society, civilization itself.

The lord was obliged to give his vassals protection and justice. Vassals not only worked the land for the Lord, they also gave 40 days w/o pay each year to serve as militia in the event of all-out war. But only 40 days, because as farmers, they needed to be home to work their fields and tend the herds.

For the most part, this system worked pretty well, as long as the lord treated his vassals well. What became a problem was when lords got greedy and decided to mobilize their army and militia to make a land grab on a neighboring lord. Ideally, Feudalism was supposed to be for protection, not conquest.

As the Church was so much a part of medieval life, it couldn’t escape being included in the feudal system. Since the Vikings were equal opportunity raiders, they had no qualms whatever about breaking into churches, convents and monasteries, putting priests and monks to the sword, raping nuns, and absconding with church treasures. This meant the Church turned to local lords for protection as well. Bishops and abbots also became vassals, receiving from the lord a specific region over which their authority lay. In return, they had to provide some service to the Lord. Monasteries produced different goods which they paid as tribute, and priests were often made the special private clergy for the noble’s family. This became a problem when loyalty to the lord conflicted with a ruling from or mission assigned by the Church. Who were the abbots, priest and bishops to obey, the duke 10 minutes from here, or the Pope weeks away in Rome? In the 10th and early 11th Cs the popes were in no position to challenge anyone. The office fell into decay after becoming a prize sought by the Roman nobility.

What made the latter Middle Ages so complex was the massive intrigue that took place between Nobles and Church officials who learned how to play the feudal game. Society was governed by strict rules. But there were always ways to get around them. And when one couldn’t get around them, if you had enough money or a big enough army, why bother with rules when you can write your own, or pay the rule-interpreters to interpret them in your favor. We know how complex political maneuvering can be today. Compared to Europe of the High Middle Ages, we’re infants in a nursery. Don’t forget, it was that era and system that produced Machiavelli.

On a positive note; while there were a few corrupt Church officials who saw religious office as just another way to gain political power, most bishops, priests and abbots sought to influence for the better the behavior of the feudal nobles so their vassals would be taken care of in an ethical manner. In time, their work added the Christian virtues to a code of knightly conduct that came to be called Chivalry. Now, to be clear, chivalry ended up being more an ideal than a practice. A few knights and members of the nobility embraced the Chivalric ideals but others just took advantage of those who sought to live by them.

Knights in shining armor, riding off on dangerous quests to rescue fair maidens makes for fun stories, but it’s not the way Chivalry played out in history. It was an ideal the Church worked hard to instill in the increasingly brutal Feudal Age. Bishops tried to impose limitations on warfare. In the 11th C they inaugurated a couple initiatives called the Peace of God and the Truce of God. The Peace of God banned anyone who pillaged sacred places or refused to spare noncombatants from being able to participate at Communion or receiving any of the other sacraments. The Truce of God set up periods of time when no fighting was allowed. For instance, no combat could be conducted from sunset Wednesday to sunrise Monday and during other special seasons, such as Lent. Good ideas, but both rules were conveniently set aside when they worked contrary to some knights desires.

During the 11th C, the controversy between Church and State centered on the problem of what’s called Investiture. And this goes back now to something that had been in tension for centuries, and was renewed in the crowning of Charlemagne.

It was supposed to be that bishops and abbots were appointed to their office by the Church. Their spiritual authority was invested in them by a Church official. But because bishops and abbots had taken on certain feudal responsibilities, they were invested with civil authority by the local noble; sometimes by the king himself. Problems arose when a king refused to invest a bishop because said bishop was more interested in the Church’s cause than the king’s. He wanted someone more compliant to his agenda, while the Church wanted leaders who would look out for her interests. It was a constant game of brinkmanship, in which whatever institution held most influence, had the say in who lead the churches and monasteries. In places like Germany where the king was strong, bishops and abbots were his men. Where the Church had greater influence, it was the bishops and abbots who dominated political affairs.

But that was the controversy of the 11th C. The Church of the 10th could see the way things were headed in its affiliation with the Throne and knew it was not prepared to challenge kings and emperors. It needed to set its own house in order because things had slipped badly for a couple hundred years. Moral corruption had infected large portions of the clergy and learning had sunk to a low. Many of the clergy were illiterate and marked by grave superstitions. It was time for renewal and reform. This was led by the Benedictine order of Cluny, founded in 910. From their original monastery in Eastern France, the Benedictines exerted a powerful impulse of reform within the feudal Church. The Cluniac program began as monastic reform movement, but spread to the European Church as a whole. It enforced the celibacy of priests and abolished the purchase of church offices; a corrupt practice called Simony.

The goal of the Clunaic reformers was to free the Church from secular control and return it to the Pope’s authority. Nearly 300 monasteries were freed from control by the nobles, and in 1059 the papacy itself was delivered from secular interference. This came about by the creation of the College of Cardinals, which from then on selected the Pope.

The man who led the much-needed reform of the papacy was an arch-deacon named Hildebrand. He was elected pope in 1073 and given the title Gregory VII. He claimed more power for the papal office than had been known before and worked for the creation of a Christian Empire under the Pope’s control. Rather than equality between Church and State, Gregory said spiritual power was supreme and therefore trumped the temporal power of nobles and kings. In 1075 he banned investiture by civil officials and threatened to excommunicate anyone who performed it as well as any clergy who submitted to it. This was a virtual declaration of war on Europe’s rulers since most of them practiced lay investiture.

The climax to the struggle between Pope Gregory and Europe’s nobility took place in his clash with the emperor Henry IV. The pope accused Henry of Simony in appointing his own choice to be the archbishop of Milan. Gregory summoned Henry to Rome to explain his conduct. Henry refused to go but convened a synod of German bishops in 1076 that declared Gregory a usurper and unfit to be Pope. The synod declared, “Wherefore henceforth we renounce, now and for the future, all obedience to you.” In retaliation, Gregory excommunicated Henry and deposed him, absolving his subjects from their oaths of allegiance.

Now, remember how sacred and firm those feudal oaths between lord and vassal were! The Pope, who was supposed to be God’s representative on Earth, sent a message to all Henry’s subjects saying not only was Henry booted out of the Church, and so destined to the eternal flames of hell, he was no longer king or emperor; their bonds to him were dissolved. Furthermore, to continue to give allegiance to Henry was to defy the Pope who opens and closes the door to heaven. Uhh, do you really want to do that? Can you see where this is going? Henry may have an army, but that army has to eat and if the peasants and serfs won’t work, the army falls apart.

Henry was convinced by the German nobles who revolted against him to make peace with Pope Gregory. He appeared before the Pope in January of 1077. Dressed as a penitent, the emperor stood barefoot in the snow for 3 days and begged forgiveness until, in Gregory’s words “We loosed the chain of the anathema and at length received him … into the lap of the Holy Mother Church.”

This dramatic humiliation of an emperor did not forever end the contest between the throne and the pope. But the Church made progress toward freeing itself from interference by nobles. The problem of investiture was settled in 1122 by a compromise known as the Concordat of Worms. The Church kept the right to appoint the holder of a church office, then the nobles endorsed him.

The Popes who followed Gregory added little to the authority of the papacy. They also insisted society was organized under the pope as its visible head, and he was guarded against all possibility of error by the Apostle Peter perpetually-present in his successors.

During the Middle Ages, for the first time, Europe became conscious of itself as a unity. It was the Church that facilitated that identity. Though it struggled with the challenge of how to wield power without being corrupted by it, the Church gained a level of influence over the lives of men and women that for the most part it used to benefit society.

We’re used to seeing priests and bishops of the medieval era as modern literature and movies cast them. It’s far more interesting to make them out to be villains and scoundrels, instead of godly servants of Christ who lived virtuous lives. A survey of movies and novels written about the Middle Ages shows that churchmen are nearly always cast in 1 of 2 ways; the best are naïve but illiterate bumblers, while the worst are conniving criminals who hide their wickedness behind a cross. While there was certainly a handful of each of these 2 type-casts; the vast majority of priests and monks were simply godly lovers of Jesus who worked tirelessly to bring His love and truth to the people of their day. Guys like that just don’t make for very interesting characters in a murder mystery set in a medieval monastery.

by Lance Ralston | Jul 27, 2014 | English |

The title of this 48th episode of CS is “Charlemagne – Part 1.”

The political landscape of our time is dominated by the idea that nation-states are autonomous, sovereign societies in which religion at best plays a minor role. Religion may be an influence in shaping some aspects of culture, but affiliation with a religious group is voluntary and distinct from the rest of society.

What we need to understand if we’re going to be objective in our study of history is that, that idea simply did not exist in Europe during the Middle Ages.

In the 9th C, the Frank king Charles the Great, better known as Charlemagne, sought to makes Augustine’s vision of society in his magnum opus, The City of God, a reality. He merged Church and State, fusing a new political-religious alliance. His was a conscious effort to merge the Roman Catholic Church with what was left of the old Roman political house, creating a hybrid Holy Roman Empire. The product became what’s called Medieval European Christendom.

How did it come about that Jesus’ statement that His kingdom was not of this world, could be so massively reworked? Let’s find out.

300 years after the Fall of the Western Empire to the Goths, the idea and ideal of Empire continued to fire the imaginations of the people of Europe. Though the barbarians were divided into several groups and remained at constant war with each other, the longing for peace and unity that marked the region under the Roman Eagle held a powerful attraction. Many looked forward to the day when a new Empire would appear. Just as the Eastern Empire centered at Constantinople saw itself as Rome-still, the vestiges of the Western Empire along with their German neighbors hoped the Empire would (insert Star Wars reference) strike back and rise again.

By merging the Roman and Germanic religions, customs and peoples, the Franks under Clovis became the odds on favorite to accomplish what many hoped for. But Clovis’ dynasty began to fall apart not long after he passed from the scene. His descendants were at odds with each other, vying for pre-eminence. They became adept at intrigue and treachery.

The power vacuum created by their squabbles gave room for wealthy aristocrats to gain power. Like 2 dogs fighting over a scrap of food, while they’re busy snarling and snapping at each other, the cat comes and quietly steals away what they’re fighting over. So it was with Clovis’ descendants, the Merovingians. While they fought each other, the landed nobility quietly stole more and more of their authority. Among these emerging aristocrats was one who worked his way into the heart of power to become the most influential figure in the kingdom. He was called the “majordomo” or “mayor of the palace.”

The majordomo was the real power behind the throne. He ran the kingdom while the king served as little more than a ceremonial figurehead. The idea was that the son of the previous king wasn’t necessarily the one most fit to rule just because of his birth. So while the title went legally to him, the day-to-day business of running the realm was better served by another with the skills to get the job done.

In 680, Pepin II became majordomo for the Franks. He made no pretense of his desire to supplant the Merovingian line with his own as the de-facto rulers. He took the title of Duke and Prince of the Franks and made moves to ensure his line would eventually sit the throne.

His son, Charles Martel, became majordomo in 715. Charles allowed the Merovingian kings to retain their title but as little more than figureheads. What catapulted Charles to the throne was his defeat of the Muslims in 732.

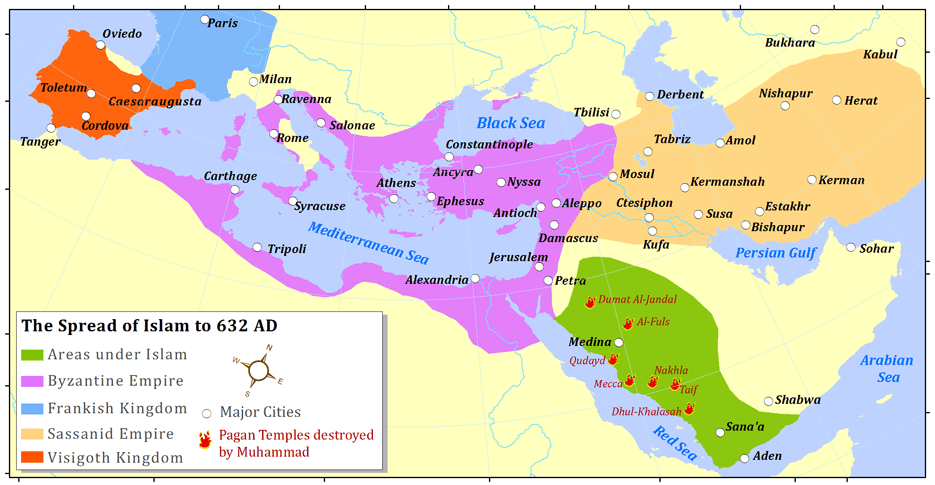

In 711 a Muslim army from North Africa called the Moors invaded Spain and rolled back the weak kingdom of the Visigoths by 718. With the Iberian Peninsula under their control, the Moors began raiding across the Pyrenees into Southern Gaul. Until this time, the Muslims had advanced at a steady pace out of the Middle East, across North Africa, then into Europe. It seemed no one in the West could stop them and the fear of the infidel hordes running amuck throughout the lands of Christendom was a terror.

In 732 Charles led the Franks against a Moor raiding party near Tours, deep inside the Frank’s land. He inflicted such heavy losses the Moors retreated to Spain and were never again a major threat to Western Europe. For this and his other conquests, Charles was called Martell – “the Hammer.”

Martel’s son, Pepin III, also known as Pepin the Short, considered it time to make the power of the Frank majordomo more official. Why not give the title of “king” to the guy who was actually ruling, instead of some royal spoiled brat who thought armies were just large toys to play with? Pepin III asked Pope Zachary for a ruling saying whoever actually wielded power was the legal ruler. He got what he wanted, promptly deposed the last Merovingian King, Childeric III, and was crowned the first of the Carolingian kings by the bishop of Mainz in 751. Childeric was quietly shuffled off to a monastery where he was told to mind his manners or he’d wake up dead one day. Then, 3 years after Pepin’s coronation, Pope Stephen II himself blessed him by making the trip from Rome to Paris and personally anointing Pepin as the “Chosen of the Lord.”

Both Popes Zachary and Stephen were eager to shore up the alliance with the Franks begun with Clovis because of the emerging problem with the Lombards. They’d already conquered Ravenna, the center of Byzantine power in Italy. The Lombards demanded tribute from the pope and threatened to take Rome if it wasn’t paid. With Pepin’s coronation, the Church at Rome secured his promise of protection and his pledge to give the pope the territory of Ravenna once it was recovered. In 756, the Franks forced the Lombards to surrender several of their Italian conquests, and Pepin kept his promise to give Ravenna to the Pope. This was known as the “Donation of Pepin,” and came to be called the Papal States. This made the Pope a temporal ruler over a strip of land cutting across Italy.

This alliance between the Franks and the Church at Rome, or more properly, between the Carolingian kings and the Popes, had a dramatic impact on the course of European politics for centuries to come. It sped up the separation of the Latin and Greek Church by giving the Popes an ally to replace the Byzantines. And it created the Papal States which will play a major role in Italian politics all the way up to the late 19th C.

But one of the most significant issues was that with the Popes taking a hand in anointing kings, it set the stage for the eventual vying for power between Church and State, between Pope and Emperor. The question became: Who was really in charge? The Pope—who by reason of setting the crown on the king’s head, sanctioned his rule, or the King—whose armies were the enforcement end of the Pope’s staff and protected him from enemies? Do popes make kings, or do kings make popes? Fire up the medieval merry-go-round.

It was Pepin III’s son who took all that his father and grandfather had done and put the cap on it. His name also was Charles; Charles the Great; known to us as Charlemagne.

When Charlemagne succeeded his father in 768 he had a far-reaching vision of making Central Europe into a new Empire, similar to the Golden Age of Rome, but this time enlightened by Christianity.

To accomplish this vision he had 3 objectives:

1) Boost the Franks military might so they could dominate Europe,

2) Secure an alliance with the Church to unite Europe under one faith,

3) Make this European base an intellectual center.

Charlemagne’s success, if we can call it that, set the course for Europe for the next thousand years.

Charles the Great was a big man. At 6’3” he was a full foot taller than average at that time. But to those who met him he seemed even bigger because he was one of those people who had an extra dose of gravitas. He was skilled at arms and was always at the head of the army when they went into battle, which he led the Franks in every year.

The Merovingians had wasted the strength of the Franks in incessant civil wars. Charlemagne united the Franks and set them on the task of conquest. He took advantage of feuds among the Muslims Moors in Spain and in 778 crossed the Pyrenees in an attempt to reclaim the Iberian Peninsula. His first campaign was met with minor success but later expeditions drove the Moors back to the Ebro River and established a frontier known as the Spanish March centered at Barcelona.

Then Charlemagne conquered the Bavarians and Saxons, last of the independent Germanic tribes. He ruthlessly attempted to stamp out the residue of Germanic paganism by passing harsh laws, such as saying eating meat during Lent, cremating the dead, and pretending to be baptized, were offenses punishable by death.

The kingdom’s eastern frontier was continually threatened by Asiatic nomads related to the Huns known as the Slavs and Avars. Charlemagne decimated the Avars and set up his own military province in the Danube valley to guard against future plundering. He called this the East March, later called Austria.

Then, like his father before him, Charlemagne sought to take a hand in Italian politics. The Lombards invaded that territory Pepin had given the Church. So, in 774 at the Pope’s urging, Charlemagne once again defeated the Lombards and proclaimed himself their king.

The Lombard’s campaigns and conquests made it clear the Popes needed protection. Only one military and political power had that ability, the Frank king. Charlemagne, on the other hand, needed divine sanction to accomplish his goal of uniting Europe. Only one authority possessed the religious mojo to do that – the Pope. Can you see where this is headed?

April 25, 799 was St. Mark’s Day, a day set aside for repentance and prayer. It seemed the right thing to do since Italy had been stricken by numerous problems, including plague and pestilence. So Pope Leo III led a procession thru Rome beseeching God’s forgiveness and blessing.

The procession wound thru the middle of the city to St. Peter’s. As it turned a corner, armed men rushed at the pope. They drove off his attendants, and pulled Leo off his horse, carting him off to a monastery favorable to their cause. That being that they were officials and dignitaries loyal to the previous pope, Adrian I. Perjury and adultery were the charges leveled at Leo. The pope’s supporters tracked him down and rescued him.

This created a furor that sparked on-going riots that could not be quelled. So Pope Leo once again sent for Charlemagne. He crossed the Alps with an army, determined to settle the pope’s problem once and for all. He put down the unrest and in December presided over a large assembly of bishops, nobles, diplomats and malcontents. In other words, anyone who considered themselves someone and held a hand in the political game was in attendance. Then, the pope, wielding a Bible, took an oath swearing innocence in all charges against him. That brought the mutiny against him to an effective end. But it set the stage for a far more momentous development.

2 days later, Christmas Day AD 800, Charlemagne arrived at St. Peter’s with a large retinue for the Christmas service. Pope Leo sang the mass and the king knelt in prayer in front of Peter’s crypt. The pope approached the kneeling monarch carrying a golden crown. Leo placed it on Charlemagne’s head as the congregation cried: “To Charles, the most pious, crowned Augustus by God, to the great peace-making Emperor, long life and victory!” The pope then prostrated himself. Charlemagne, King of the Franks, had just become the first king of the Holy Roman Empire.

We’ll conclude Charlemagne’s story next time.

by Lance Ralston | Jul 20, 2014 | English |

This week’s episode is titled – “Challenge.”

We’ve tracked the development and growth of the Church in the East over a few episodes. To be clear, we’re talking about the Church which made its headquarters in the city of Seleucia, twin city to the Persian capital of Ctesiphon, in the region known as Mesopotamia. What today historians refer to as The Church in the East called itself the Assyrian Church. But it was known by the Catholic Church in the West with its twin centers at Rome and Constantinople, by the disparaging title of the Nestorian Church because it continued on in the theological tradition of Bishop Nestorius, declared heretical by the Councils of Ephesus in 431 and Chalcedon 20 years later. As we’ve seen, it’s doubtful what Nestorius taught about the nature of Christ was truly errant. But Cyril, bishop of Alexandria, more for political reasons than from a concern for theological purity, convinced his peers Nestorius was a heretic and had him and his followers banished. They moved East and formed the core of the Church in the East.

While that branch of the Church thrived during the European Middle Ages, the Western Catholic Church coalesced around 2 centers; Rome and Constantinople. Though they’d reached agreement over the doctrinal issues regarding the nature of Christ and expelled both the Nestorians to the East and the Monophysite Jacobites to their enclaves in Syria and Egypt, the Western and Eastern halves of the Roman Church drifted apart.

The Council of Constantinople in 692 marked one of several turning points in the eventual rift between Rome and Constantinople. Called by the Emperor, the Council was attended only by Eastern Bishops. It dealt with no real doctrinal matters but set down rules for how the Church was to be organized and worship conducted. The problem is that several of the decisions went contrary to the long-held practice in Rome and the churches in Western Europe that looked to it. The Pope rejected the Council. à And the gulf between Rome and Constantinople widened.

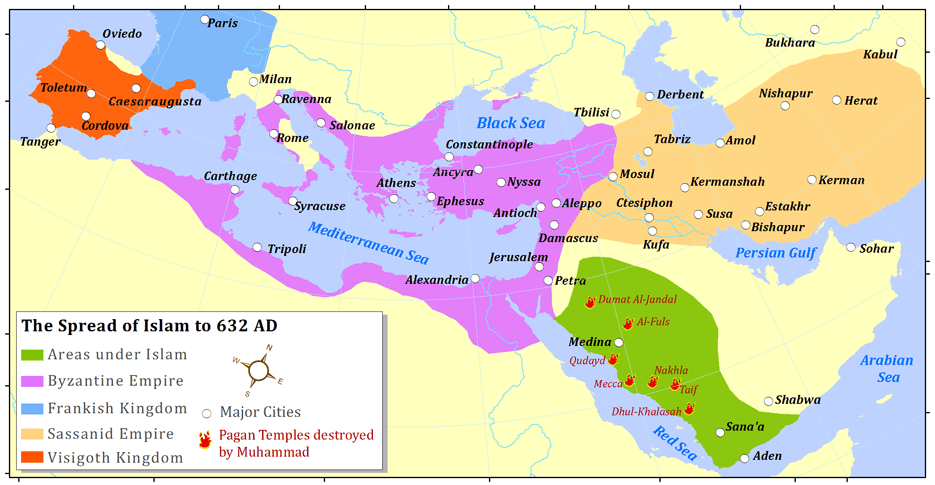

This gap between the Eastern and Western halves of the Church mirrored what was happening in the Empire at large. As we’ve seen, Justinian I tried to revive the gory of the Roman Empire in the 6th C, but after his death, the Empire quickly reverted to its path toward disintegration. What helped this dissolution was the emergence of Islam from the southeast corner of the Empire.

Historically, the Arabs were a people of multiple tribes who shared both a common culture and distrust of one another which fueled endless conflict. But the early 7th C saw them united by a new and militant religion. The endless struggles that had kept them at each other’s throats, were merged into a shared mission of setting them at everyone else’s. Why steal from each other in generations of just transferring the same loot back and forth when they could unite and grab new plunder from their neighbors?

And so much the better when those neighbors who used to be too strong to attack, were now in decline and under-defended?

It was a Perfect Storm. The emergence of the Muslim armies in the early 7th C, bursting forth from the furnace that forged them, came right at the time when the once unstoppable might of the Roman Empire was finally a relic of a bygone age. Constantinople was able to hold the invaders at bay for another 700 years, but Islam spread quickly over other lands of the once great Empire; into the Middle East, North Africa, and was even able to get a foothold in Europe when they jumped the Straits of Gibraltar and landed in Spain. In the East, the Muslims swept up into Rome’s ancient nemesis, Persia, and quickly subdued it as well.

It all began with the birth of an Arab named Muhammad in 570.

Since this is a podcast on the history of Christianity rather than Islam, I’ll be brief in this review of the new religion that moved the Arabs out of their peninsula during the 7th C.

Islam marks its beginning to the Hegira, Muhammad’s move from his hometown of Mecca to the city of Medina in AD 622. This began the successful phase of his preaching. Muhammad built a theology that included elements of Judaism, Christianity, and Arabian polytheism.

While there’s much talk today about Islam’s place with Judaism and Christianity as a monotheistic religion, a little research reveals Muhammad really only elevated one of the Arab’s gods over the others – that is Il-Allah, or as it is known today – Allah. Allah was the moon god and patron deity of Muhammad’s Quraysh tribe. The enduring proof of this is the symbol of the crescent moon that adorns the top of every Muslim mosque and minaret and is the universal symbol of Islam.

Muhammad’s new religion included elements of both Judaism and Christianity because he hoped to include both groups in his new movement. The Jews refused his efforts while several Christians joined the new movement. It’s understandable why. The church Muhammad was familiar with was one that had been co-opted by Arab superstition. It hardly resembled Biblical Christianity. It was ripe pickings for the emergent faith. When Islam later ran into more orthodox Christian communities, they refused the new faith. Muhammad was incensed at the Jews and Christians refusal to join, so they became the object of his wrath.

Part of Muhammad’s genius was that he sanctified the Arabic penchant for war by uniting the tribes and sending them on the mission of taking Islam to the rest of the world thru the power of the sword. Loot was made over as a religious bonus, evidence of divine favor.

Islam’s rapid spread across Western Asia and North Africa was facilitated by the vacuum left from the chronic wars between Rome and Persia. Just prior to the Arab conquests, the old combatants had concluded yet another round in their long contest and were exhausted!

In the 2nd decade of the 7th C, the Persians conquered Syria and Palestine from the Romans, took Antioch, pillaged Jerusalem, then conquered Alexandria in Egypt. That means the Persians ruled what had been the 2nd and 3rd most populous cities of the Roman Empire. They conquered most of Asia Minor and set-up camp just across the Bosporus from Constantinople.

Then, in one of the great reversals of history, Emperor Heraclius rallied the Eastern Empire and launched a Holy War to reclaim the lands lost to the Persians. They retook Syria, Palestine, Egypt and invaded deep into Persia. You can well imagine what all this war did politically, environmentally and economically to the region. It left it exhausted. Like a body whose defenses are down, the Eastern Empire was ripe for a new invasion. And look; Oh goodie à Here come the Arabs swinging their scimitars. The Arab advance was nothing less than spectacular.

Muhammad died in 632 and was followed by a series of associates known as caliphs. In 635 the Arabs took Damascus, in 638 they captured Jerusalem. Alexandria fell in 642. Then the Muslim armies turned north and swept up into the demoralized region of Persia. By 650 it was theirs, as were parts of Asia Minor and a large part of North Africa.

The Muslims realized conquering the Mediterranean would require they become a naval power. They did and began taking strategic islands in the Eastern and Central sea. In the 670s with their new navy, they began taking shots at Constantinople but were chased off by a new invention – Greek Fire.

They conquered Carthage in 697, the center of Byzantine might in North Africa. Then in 715, they hopped the Straits of Gibraltar and landed in Spain, bringing the Visigothic rule there to an end. They then crossed the Pyrenees and laid claim to Southwestern Gaul. It wasn’t ill the Battle of Tours in 732 that the Franks under Charles Martel were able to put a halt to the Muslim advance. That also marks the beginning of the ever so slow roll-back of Muslim domination in the Iberian Peninsula.

But what territory Islam lost in the far western reach of their holdings was made up for by their advances in the East. During the 8th C, they reached into Punjab in India and deep into Central Asia.

The major islands of the Mediterranean became coins that flipped from Byzantine to Muslim, then back again. The Muslims even managed to settle a couple of colonies on the coast of Italy. They raided Rome.

These conquests tapered off as the old tendency toward animosity between the Arabic tribes returned. The thing that had united them, Islam, became one more thing to fight over. The main point of contention was over who was supposed to lead the Umma – the Muslim community. Islam fractured into different camps who turned their scimitars on each other, and the rest of the world breathed a collective sigh of relief.

The Church in those lands that now lay under the Crescent moon suffered. Islam was supposed to hold a certain respect for what they called “The People of the Book” – meaning Christians and Jews. Moses and Jesus were considered great prophets in Islam. While pagans had to convert to Islam, Christians and Jews were allowed to continue in their faith, as long as they paid a penalty tax. The treatment of Christians varied widely across Muslims lands. Their fate was determined by the intensity of the rulers’ faith and adherence to Islam. This was largely due to the conflicting instructions found in the Koran about how to treat people of other faiths.

In Islam, later revelation supersedes earlier pronouncements. Early in Muhammad’s career, he hoped to win Christians by persuasion to his cause so he called for kindly treatment of them. Later, when he had some power and Christians proved intractable, he spoke more stridently and urged their forced compliance. Conversion FROM Islam to any other religion was to be punished by execution. But the Koran isn’t set down in a chronological sequence and readers don’t always know which was an earlier and which a later revelation. Some Muslims rulers were stern and read the harsh passages as being the rule. They persecuted Christian and tried to eradicate the Church. Others believed the call to a more merciful relationship with Christians was a higher morality and followed that. Churches were allowed to meet under such rulers, but public demonstrations of faith were banned and no new church building was permitted.

Interestingly, there was a flowering of Arabic culture that took place due to rule by benevolent Muslims. Because Christian scholarship was allowed, the Classics of Greek and Roman civilization were translated into Arabic BY CHRISTIAN CLERGY and SCHOLARS. It was this that led to the emergence of the Arabic Golden Age modern historians make so much of. That such a Golden Age was sparked and enabled by Christian scholars giving Muslims access to the works of classical antiquity is rarely mentioned.

The severe limits placed on the Faith by even lenient Muslim rulers, combined with the harsh treatment of the Church in other places led to widespread loses by the Church in terms of population and influence. Catholic Christians living in North Africa fled north to Europe where they were welcomed by those of similar faith. But the Jacobite Monophysite community was left behind to languish, and the vibrant church culture that had once dominated the region was nearly lost. The resurgent radical Islam of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt is now putting the final nails in the coffin of the Coptic Church, the spiritual heirs to that once vibrant history.

Nearly everywhere Islam spread, it was accompanied by mass defections of marginal Christians to the new faith. Pragmatism isn’t such a modern philosophy after all. Many nominal Christians assumed the single God of Islam was the same as the one God of Christianity and He must favor the Muslims – I mean > look at how successful they are in spreading their religion. Might makes right – Right? // Well, maybe it doesn’t . . . Shhh! Not so loud, the mullahs might hear and their scimitars are sharp.

As many had converted to the newly emergent Christianity under the auspices of Constantine in the early 4th Century, now many converted to Islam under the caliphates in the 7th.

Along with the restrictions placed on those Christians who refused to convert to Islam was added a practice the Muslims picked up from the Zoroastrian rulers of Persia. They required Christians to wear a distinctive badge and prohibited them from serving in the army. That was probably for the best since the army was used specifically to spread the Faith by the sword – the Muslim practice of jihad. But being banned from the military meant they were prohibited the use of arms, and forced to wear distinctive clothing meant easy identification for those hostile elements who saw the presence of Christians as contrary to the will of Allah. Christians became targets of public shame and often, violence. Since conversions FROM Islam were punishable by death, while conversion TO Islam was rewarded, even in the most lenient realms under the banner of Crescent Moon, the church experienced a steady decline.

As Islam settled in and became the dominant cultural force throughout its domains, most of the Christian communities that remained became tradition-bound. They reacted strongly against any innovations, fearing they were dangerous deviations from the Faith they’d held to so tenaciously in spite of persecution. Another reason they rejected change was for fear it might lead to success and the church would grow. Growth meant the Muslim authorities paying closer attention, and that was something they wanted to avoid at all costs. For that reason, to this day the Church in Muslim lands tends to be archaic and bound to traditions practiced for hundreds of years.

by Lance Ralston | Jul 6, 2014 | English |

This episode of Communio Sanctorum is titled, “Liturgy.”

What comes to mind when you hear that word – “Liturgy.”

Most likely—it brings up various associations for different people. Some find great comfort in what the word connotes because it recalls a time in their life of close connection to God. Others think of empty rituals that obscure, rather than bring closer a sense of the sacred.

The following is by no means meant as a comprehensive study of Christian liturgy. Far from it. That would take hours. This is just a thumbnail sketch of the genesis of some of the liturgical traditions of the Church.

First off, using a broad-brush the word ‘liturgy’ refers to the order and parts of a service held in a church. Even though most non-denominational, Evangelical churches like the one I’m a part of doesn’t call our order of service on a Sunday morning a “liturgy” – that’s in fact what it is. Technically, the word “Liturgy” means “service.” But it’s come to refer to all the various parts of a church service, that is, when a local church community gathers for worship. It includes the order the various events occur, how they’re conducted, what scripts are recited, what music is used, which rituals are performed, even what physical objects are employed to conduct them; things like special clothes, furniture, & implements.

Even within the same church, there may be different liturgies for different events and seasons of the year.

For convenience sake, churches tend to get put into 2 broad categories; liturgical & non-liturgical. Liturgical churches are often also called “high-church” meaning they have a set tradition for the order of the service that includes special vestments for priests & officiants; and follow a pattern for their service that’s been conducted the same way for many years. Certain portions of the Bible are read, then a reading from another treasured tome of that denomination, people sit, stand and kneel at designated times, and clergy follows a set route through the sanctuary.

In a non-liturgical church, while they may follow a regular order of service, there’s little of the formalism and ritual used in a high-church service. In many liturgical churches, the message a pastor or priest is to share each week is spelled out by the denominational hierarchy in a manual sent out annually. In a non-liturgical church, the pastor is typically free to pick what he wants to speak on.

The great liturgies arose in the 4th to 6th Cs then codified in the 6th & 7th. They were much more elaborate than the order of service practiced in the churches of the 2nd & 3rd Cs.

Several factors led to the creation of liturgies à

First: There’s a tendency to settle on a standard way to say things when it comes to the beliefs & practices of a group. When someone states something well, or does something in an impressive way, it tends to get repeated.

Second: Bishops & elders tended to take what they learned in one place and transplanted it wherever they went.

Third: A written liturgy made the services more orderly.

Fourth: The desire to hold on to what was thought to be passed down by the Apostles became a priority. This worked against any desire for change.

Fifth: A devotion to orthodoxy, combined for a concern about heresy tended to sanctify what was old and opposed innovation. Changes in a liturgy sparked controversy.

The main liturgies that emerged during the 5th & 6th Cs bear similarities in structure & theme; even in wording, while also having distinct features.

The main liturgical traditions can be listed as . . .

In the East

The Alexandrian or sometimes called Egyptian liturgies.

The West Syrian family includes the Jerusalem, Clementine, & Constantinoplitan liturgies.

The East Syrian family includes the liturgies that were used in the Nestorian churches of the East.

In the West, the principal liturgical families were Roman, Gallican, Ambrosian, Mozarbic & Celtic.

As we saw in Epsidoe 41, Pope Gregory the Great in the 7th C embellished the liturgy & ritual practiced in the Western Roman Church. Elaborate rituals were already a long-time tradition in the Eastern Church, influenced as it was by the court of Constantinople.

If Augustine laid down the theological base for the Medieval church, Pope Gregory can be credited with its liturgical foundation. But no one should assume Gregory created things out of a vacuum. There was already extensive liturgical fodder for him to draw from.

And this brings us to a 4th C document called The Pilgrimage of Etheria – or The Travels of Egeria.

We’re not sure who she was but can narrow it down to either a nun or a well-to-do woman of self-sufficient means from Northern Spain.

She toured the Middle East at the end of the 4th C, then wrote a long letter to some women she call her sisters & friends, chronicling her 3 year adventure. While the beginning and end of the letter are missing, the main body gives a detailed account of her trip, made from extensive notes.

The first part describes her journey from Egypt to Sinai, ending at Constantinople. She visited Edessa, and travelled extensively in Palestine. The second and much longer section is a detailed account of the services and observances of the church in Jerusalem, centered on what the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

What’s remarkable in reading her account is the tremendous sense of freedom and safety Egeria seems to have had as she travelled over long distances in hostile environs. She was accompanied for a time by some soldiers, and no doubt these provided a measure of security. But that she felt safe WITH THEM, is remarkable and speaks to the impact the Faith was already having on the morality of the ancient world.

Remarkable as well was the large number of Christian communes, monks & bishops she met on her travels. Every place mentioned in the Bible already had a shrine or church. As she visited each, using her Bible as a guide, she was shown dozens of places where this or that Biblical event was supposed to have occurred.

I’ve been to the Holy Land several times. I know the many sites today that claim to be the place where this or that Bible story unfolded. Most of the sites are at best a guess. What I found fascinating about Egeria’s account is that already, by the end of the 4th C, most of these sites were already boasting to be the very place. I have to wonder if the obligatory souvenir shop was also hawking wares at each location.

You can’t read Egeria’s chronicle without being impressed with how thoroughly the Church had covered the Middle East in just 300 years, even in isolated locations; places mentioned in passing in the account of the Exodus. Every little town & village mentioned in the Old and New Testaments had a church or memorial and a group of monks ready to tell the story of what happened there. 300 years may seem like a long time, but remember that almost ALL that time was marked by persecution of Jesus’ followers.

Egeria’s account of the liturgy of the church in Jerusalem, occupying the bulk of her record, is interesting because it reveals a pretty elaborate tradition for both daily services & special days like the Holy Week. They observed the hours and Holy Service marking off the day in different periods of devotion led by the Bishop.

Accepted history tells us that the idea of a liturgical year was only just beginning in Egeria’s time. Her description of the practices of the Jerusalem Church community make clear many aspects of the liturgical year were already well along, and had been for some time.

If you’re interested in reading Egeria’s account yourself, you can find it on the net. I’ll put a link in the show notes.

http://www.ccel.org/m/mcclure/etheria/etheria.htm

by Lance Ralston | Jun 29, 2014 | English |

This episode of Communio Sanctorum is titled, “Look Who’s Driving the Bus Now.”

As noted in a previous episode, it’s difficult in recounting Church History to follow a straight narrative timeline. The expansion of the Faith into different regions means many storylines. So it’s necessary to do a certain amount of backtracking as we follow the spread of the Gospel from region to region. The problem with that though in an audio series, it can be confusing as we bounce back & forth in time. We’ve already followed Christianity’s expansion to the Far East & went from the 4th C thru about the 6th, then did a quick little jaunt all the way to the 17th C. Then in the next episode we’re back in Italy talking about the 3rd C.

This week’s episode is a case in point. We’re going to take a look at 2 interesting & important individuals in the history; not only of the Faith, but of the world. It’s a couple men we’ve already looked at – Bishop Ambrose of Milan and Emperor Theodosius I. The reason we’re considering these 2 is because their relationship was instrumental in setting the tie between Church & State that becomes one of the defining realities of Europe in the Middle Ages.

I know some of this is a repeat of earlier material. Hang with me because we need to consider the background of the players here.

Ambrose was born into the powerful Roman family of Aurelius about 340 in the German city of Trier, which served at the time as the capital of the Roman province of Gaul. Both his parents were Christians. His father held the important position of praetorian prefect. His mother was a woman of great intellect & virtue.

His father died while he was still young & as was typical for wealthy Romans of the time, Ambrose followed his father into the political arena. He was educated in Rome where he studied law, literature, & as we’d expect of someone going into politics – rhetoric. In 372 he was made the governor of the region of Liguria, its capital being Milan, the 2nd capital of Italy after Rome. In fact, in the later 4th C, Milan was the new Imperial Capital. The Western Emperors deemed Rome as both in need of major repairs & too far removed from where all the action was. For decades the Emperors in Rome were too distant from the constant campaigns against the Germanic tribes. They wanted to be closer to the action, so imperial HQs shifted to Milan.

Not long after he became governor, the famous controversy between the Arians & Catholics heated up. In 374 the Arian bishop of Milan, Auxentius, died. Of course, the Arians expected an Arian would be named to replace him. But the Catholics saw this as an opportunity to install one of their own. The ensuing controversy threatened to destroy the peace of the City, so Governor Ambrose attended the church meeting called to appoint a new bishop. He thought his presence as the chief civil magistrate would forestall rioting. Imagine that! The Christians had a reputation for getting unruly when they didn’t get their way. Sounds like LA when the Lakers win.

Yep è Those Christian in Milan! Running amok in the streets, overturning chariots & looting street vendors selling fish tacos – Shameful!

Anyway, Ambrose attended the election, hoping his presence would remind the crowd à Rioting would be forcefully suppressed. He gave a speech to those gathered about the need to show restraint & that violence would dishonor God. His message was so reasonable, his tone so honorable, when it came time to nominate candidates for the bishop’s chair, a voice called out “Ambrose for bishop!” There was a brief silence, then another voice said, “Yes, Ambrose.” Soon a whole chorus was chanting, “Ambrose for bishop. à Bishop Ambrose.”

The governor was known to be Catholic in belief, but had always shown the Arians respect in his dealing. They saw the way the political winds were blowing and knew in a straight vote, a Catholic bishop was sure to be elected. They realized Ambrose, though of the other theological camp, wouldn’t be a bad choice. So they added their voices to the call for his investiture as bishop of Milan.

At first, Ambrose vehemently refused. He was a politician, not a religious leader. He knew he was in no way prepared to lead the Church. He hadn’t even been baptized yet and had no formal training in theology. None of this mattered to the crowd who’d not take his refusal as the last word. They said he was bishop whether he liked it or not.

He fled to a colleague’s house to hide. His host received a letter from the Emperor Gratian saying it was entirely proper for the civil government to appoint qualified individuals to church leadership positions since the Church served an important role in providing social stability. If there were people serving in the political realm who’d be more effective in the religious sphere, then by all means, let them transfer to the Church. Ambrose’s friend showed him the letter & tried to reason with him but Ambrose wouldn’t budge. So the friend went to Church officials and told them where Ambrose was hiding. When they showed up at the door intent on seeing him take the seat they’d given him, he relented. Within a week he was baptized, ordained & consecrated as Bishop of Milan.

He immediately adopted the ascetic lifestyle shared by the monks. He appointed relief for the poor, donated all of his land, & committed the care of his family to his brother.

Once Ambrose became bishop, the religious toleration that had marked his posture as a political figure went out the window. A bishop must defend the Faith against error. So Ambrose took the Arians to task. He wrote several works against them and limited their access to Church life in Milan, which at the time was arguably the most influential church in the West since Milan was the seat of imperial power.

In response to Ambrose’s moves to squelch them, the Arians appealed to high-level leaders in both the civil & religious spheres at both sides of the Empire. The western Emperor Gratian was catholic while his younger successor & augustus, Valentinian II was an Arian. Ambrose tried, but was unsuccessful in swaying Valentinian to the Nicene-catholic position.

The Arian leaders felt there were enough of them in positions of influence that if they held a council, they might be able to win the day for Arianism and asked the Emperor for permission to hold one. Of course, they hid their real motive from Gratian, who thought a council during his reign a great idea and consented. Ambrose knew the real reason for the council and urged Gratian to stack the meeting with Western, pro-Nicene catholic bishops. In the council held the next year in 381 at Aquileia, Ambrose was elected to preside & the leading Arian bishops dropped out. They were then deposed by the council.

This wasn’t the end of troubles with the Arians however. Valentinian’s mother, the dynamic Justina, knew the Arians were well represented among the generals & got them to rally behind her son. They demanded 2 churches to hold Arian services in; a basilica in Milan, the other in a suburb. Saying “No” to the Emperor & his mother is usually not so good for one’s health & most students of history would assume this would be the end, not only of Ambrose’s career, but of his life. But that’s not the way this story ends.

When Ambrose denied the Arian demands, he was summoned to appear before a hastily convened court to answer for himself. His defense of the Nicene position & the necessity as bishop to defend the Faith was so eloquent the judges sat amazed. They realized there was nothing they could do to censure him w/o setting themselves in opposition to the truth & risking another riot. They released him and affirmed his right to forbid the use of the churches by the Arians.

The next day, as he performed services in the basilica, the governor of Milan tried to persuade him to compromise & give up the church in the suburb for use by the Emperor & his mother. After all, Ambrose had made his point and his concession now would be seen as an act of grace & good will. It’s precisely the kind of thing Ambrose would have urged when he was governor. But as bishop, it was a no-go. The governor wasn’t accustomed to being denied & gave orders that BOTH churches were to be turned over to the Arians for their use at Easter. Instead of being cowed, Bishop Ambrose declared:

If you demand my person, I am ready to submit: carry me to prison or to death, I will not resist; but I will never betray the Church of Christ. I will not call upon the people to [support] me; I will die at the foot of the altar rather than desert it. The rioting of the people I will not encourage: but God alone can appease it.

Ambrose & his congregation then barricaded themselves inside the church in a kind of religious filibuster. When Valentinian & his mother Justina realized the only way to gain access was to forcefully evict them & how violently the people of Milan were likely to react, the order was rescinded.

Trained in rhetoric and law, well-versed in the Greek classics, Ambrose was known as a learned scholar, familiar with both Christian & pagan sources. His sermons were marked by references to the great thinkers, not only of the past but his own day. When he was elected bishop, he embarked on a kind of crash-course in theology. His teacher was an elder from Rome named Simplician. His knowledge of Greek, rare in the West, allowed him to study the NT in its original language. He also learned Hebrew so he could deepen his understanding of the OT. He quickly gained a reputation as an excellent preacher.

As noted in a previous episode, it was under his ministry that the brilliant Augustine of Hippo was converted. Prior to moving to Milan, Augustine was unimpressed by the quality of Christian scholarship. To be blunt, he thought Christians were for the most part an uneducated rabble. Ambrose shattered that opinion. Augustine found himself drawn to his sermons and sat rapt as he heard the Gospel explained.