by Lance Ralston | Feb 16, 2014 | English |

This episode of Communio Santorum is titled, “And In the East – Part 2.”

In our last episode, we took a brief look at the Apostle Thomas’ mission to India. Then we considered the spread of the faith into Persia. Further study of the Church in the East has to return to the Council of Chalcedon in the 5th C where Bishop Nestorius was condemned as a heretic.

As we’ve seen, the debate about the deity of Christ central to the Council of Nicea in 325, declared Jesus was of the same substance as the Father. It took another hundred years before the deity-denying error of Arianism was finally quashed. But even among orthodox & catholic, Nicean-holding believers, the question was over how to understand the nature of Christ. He’s God – got it! But he’s also human. How are we to understand His dual-nature. It was at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 that issue was finally decided. And the Church of the East was deemed to hold a position that was unorthodox.

The debate was sophisticated & complex, and not a small part decided more by politics than by concern for theological purity. The loser in the debate was Bishops Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople. To make a complex issue simple, those who emphasized the unity of the 2 natures came to be called the Monophysites = meaning a single nature. They regarded Nestorius as a heretic because he emphasized the 2 natures as distinct; even to the point of saying Nestorius claimed Jesus was 2 PERSONS. That’s NOT what Nestorius said, but it’s what his opponents managed to get all but his closest supporters to believe he said. In fact, when the Council finally issued their creedal statement, Nestorius claimed they only articulated what he’d always taught. Even though the Council of Chalcedon declared Nestorianism heretical, the Church of the East continued to hold on to their view in the dual nature of Christ, in opposition to what they considered the aberrant view of monophysitism.

By the dawn of the 6th C, there were 3 main branches of the Christian church:

The Church of the West, which looked to Rome & Constantinople for leadership.

The Church of Africa, with its great center at Alexandria & an emerging center in Ethiopia;

And the Church of the East, with its center in Persia.

As we saw last episode, the Church of the East was launched from Edessa at the border between Northern Syria & Eastern Turkey. The theological school there transferred to Nisibis in Eastern Turkey in 471. It was led by the brilliant theologian Narsai. This school had a thousand students who went out from there to lead the churches of the East. Several missionary endeavors were also launched from Nisibis – just as Iona was a sending base for Celtic Christianity in the far northwest. The Eastern Church mounted successful missions among the nomadic people of the Middle East & Central Asia between the mid-5th thru 7th Cs. These included church-planting efforts among the Huns. Abraham of Kaskar who lived during the 6th C did much to plant monastic communities throughout the East.

During the first 1200 years, the Church of the East grew both geographically & numerically far more than in the West. The primary reason for this is because in the East, missionary work was largely a movement of the laity. As Europe moved into the Middle Ages with its strict feudal system, travel ground to a standstill, while in the East, trade & commerce grew. This resulted in the movement of increasing numbers of people who carried the Faith with them.

Another reason the Church in the East grew was persecution. As we saw last time, before Constantine, the persecutions of the Roman Empire pushed large numbers of believers East. Then, when the Sassanids began the Great Persecution of Christians in Persia, that pushed large numbers of the Faithful south & further East. Following the persecution that came under Shapur II, another far more severe round of persecution broke out in the mid-5th C that saw 10 bishops and 153,000 Christians massacred within a few days.

When we think of Arabia, many immediately think of Islam. But Christianity had taken root in the peninsula long before Muhammad came on the scene. In fact, a bishop from Qatar was present at the Council of Nicea in 325! The Arabian Queen Mawwiyya, whose forces defeated the Romans in 373, insisted on receiving an orthodox bishop before she would make peace. There was mission-outreach to the south-eastern region of Arabia, in what is today Yemen before the birth of Muhammad by both Nestorian & Monophysite missionaries. By the opening of the 6th C, there were dozens of churches all along the Arabian shore of the Persian Gulf.

The rise of Islam in the 7th C was to have far-reaching consequences for the Church in the East. The Persian capital at Ctesiphon fell to the Arabs in 637. Since the Church there had become a kind of Rome to the Church of the East, the impact was massive. Muslims were sometimes tolerant of religious minorities but only as communities of the disenfranchised known as dhimmi. They became ghettoes stripped of their vitality. At the same time, the Church of the East was being shredded by Muslim conquests, it was taking one of its biggest steps forward by reaching into China in the mid 7th C.

While the Church of the West grew mostly by the work of trained clergy & the missionary monks of Celtic Christianity, in the East, as often as not, it was Christian merchants & craftsmen who advanced the Faith. The Church of the East placed great emphasis on education and literacy. It was generally understood being a follower of Jesus meant an education that included reading, writing & theology. An educated laity meant an abundance of workers capable of spreading the faith – & spread it they did! Christians often found employment among less advanced people, serving in government offices, & as teachers & secretaries. They helped solve the problem of illiteracy by inventing simplified alphabets based on the Syriac language which framed their own literature & theology.

While that was at first a boon, in the end, it proved a hindrance. Those early missionaries failed to understand the principle of contextualization; that the Gospel is super-cultural; it transcends things like language & traditions. Those early missionaries who pressed rapidly into the East assumed that their Syrian-version of the Faith was the ONLY version & tried to convert those they met to that. As a consequence, while a few did accept the faith & learned Syrian-Aramaic, a few generations later, the old religions & languages reasserted themselves and Christianity was either swept away or so assimilated into the culture that it wasn’t really Biblical Christianity any longer.

The golden age of early missions in Central Asia was from the end of the 4th C to the latter part of the 9th. Then both Islam & Buddhism came onto the scene.

Northeast of Persia, the Church had an early & extensive spread around the Oxus River. By the early 4th C the cities of Merv, Herat & Samarkand had bishops.

Once the Faith was established in this region, it spread quickly further east into the basin of the Tarim River, then into the area north of the Tien Shan Mountains & Tibet. It spread along this path because that was the premier caravan route. With so many Christians engaged in trade, it was natural the Gospel was soon planted in the caravan centers.

In the 11th C the Faith began to spread among the nomadic peoples of the central Asian regions. These Christians were mostly from the Tartars & Mongol tribes of Keraits, Onguts, Uyghurs, Naimans, and Merkits.

It’s not clear exactly when Christianity reached Tibet, but it most likely arrived there by the 6th C. The territory of the ancient Tibetans stretched farther west & north than the present-day nation, & they had extensive contact with the nomadic tribes of Central Asia. A vibrant church existed in Tibet by the 8th C. The patriarch of the Assyrian Church in Mesopotamia, Timothy I, wrote from Baghdad in 782 that the Christian community in Tibet was one of the largest groups under his oversight. He appointed a Tibetan patriarch to oversee the many churches there. The center of the Tibetan church was located at Lhasa and the Church thrived there until the late 13th C when Buddhism swept through the region.

An inscription carved into a large boulder at the entrance to the pass at Tangtse, once part of Tibet but now in India, has 3 crosses with some writing indicating the presence of the Christian Faith. The pass was one of the main ancient trade routes between Lhasa and Bactria. The crosses are stylistically from the Church of the East, and one of the words appears to be “Jesus.” Another inscription reads, “In the year 210 came Nosfarn from Samarkand as an emissary to the Khan of Tibet.” That might not seem like a reference to Christianity until you take a closer look at the date. 210! That only makes sense in reference to measuring time since the birth of Christ, which was already a practice in the Church.

The aforementioned Timothy I became Patriarch of the Assyrian church about 780. His church was located in the ancient Mesopotamian city of Seleucia, the larger twin to the Persian capital of Ctesiphon. He was 52 & well past the average life expectancy for people of the time. Timothy lived into his 90’s, dying in 823. During his long life, he devoted himself to spiritual conquest as energetically as Alexander the Great had to the military kind. While Alexander built an earthly empire, Timothy sought to expand the Kingdom of God.

At every point, Timothy’s career smashes everything we think we know about the history of Christianity at that time. He alters ideas about the geographical spread of the Faith, its relationship with political power, its cultural influence, & its interaction with other religions. In terms of his prestige & the geographical extent of his authority, Timothy was the most significant Christian leader of his day; far more influential than the pope in Rome or the patriarch in Constantinople. A quarter of the world’s Christians looked to him as both a spiritual & political head.

No responsible historian of Christianity would leave out Europe. Omitting Asia from the record is just as unthinkable. We can’t understand Christian history without Asia or Asian history without Christianity. The Church of the East cared little for European developments. Timothy I knew about his European contemporary Charlemagne. The Frankish ruler exchanged diplomatic missions with the Muslim Caliphate, a development of which the leader of the Church in the East would have been apprised. Timothy also knew Rome had its own leader called the Pope. He was certainly aware of the tension between the Pope & the Patriarch of Constantinople over who was the de-facto leader of the Christian world. Timothy probably thought their squabble silly. Wasn’t it obvious that the Church of the East was heir to the primitive church? If Rome drew its authority from Peter, Mesopotamia looked to Christ himself. After all, Jesus was a descendant of that ancient Mesopotamian Abraham. And wasn’t Mesopotamia the original source of culture & civilization, not to mention the location of the Garden of Eden? It was the East, rather than the West, that first embraced the Gospel. The natural home of Christianity was in Mesopotamia & Points East. According to the geographical wisdom of the time, Seleucia stood at the center of the world’s routes of trade & communication, equally placed between the civilizations that looked respectively to the West & the East.

All over the lands of modern-day Iraq & Iran believers built huge & enduring churches. Because of its setting close to the Roman frontier, but far enough beyond to avoid interference—Mesopotamia retained a powerful Christian culture that lasted through the 13th C. Throughout the European Middle Ages the Mesopotamian church was as much a cultural & spiritual Christian headquarters as France or Germany or even that outstanding missionary base of Ireland.

Several Mesopotamian cities like Basra, Mosul, Kirkuk, & Tikrit were thriving centers of Christianity for centuries after the arrival of Islam. In 800 AD, these churches & the schools attached to them were repositories of the classical scholarship of the Greeks, Romans & Persians that Western Europe would not access for another 400 years!

Simply put, there was no “Dark Age” in the Church of the East. From Timothy I’s perspective, the culture & scholarship of the ancient world was never lost. More importantly, the Church of the East countenanced no break between the primitive church that rose in Jerusalem in the Book of Acts and themselves.

Consider this: We can easily contrast the Latin-speaking, feudal world of the European Middle Ages with the ancient Middle-Eastern church rooted in a Greek & Aramaic speaking culture. The Medieval Church of Europe saw itself as pretty far removed from the Early Church. Both in language & thought forms, they were culturally distinct & distant. But in Timothy I’s time, that is, the early 9th C, the Church of the East still spoke Greek & Aramaic. Its members shared the same basic Middle Eastern culture & would continue to do so for centuries. As late as the 13th, they still called themselves “Nazarenes,” a title the first Christians used. They called Jesus “Yeshua.” Clergy were given the title “rabban” meaning teacher or master, related to the Hebrew – “rabbi.”

Eastern theologians used the same literary style as the authors of the Jewish Talmud rather than the theological works of Western Europe. As Philip Jenkins says, if we ever wanted to speculate on what the early church might have looked like if it had developed while avoiding its alliance with Roman state power, we have but to look East.

Repeatedly, we find Patriarch Timothy I referring to the fact that the Churches of the East used texts that were lost to & forgotten in the West. Because of their close proximity to the setting of so much Jewish and early Christian history, Eastern scholars had abundant access to ancient scriptures & texts. One hint of what was available comes from one of Timothy’s letters.

Written in 800, Timothy answered the questions of a Jew in the process of converting to Christianity. This Jew told the Patriarch of the recent finding of a large hoard of ancient manuscripts, both biblical & apocryphal, in a cave near Jericho. The documents had been acquired by Jerusalem’s Jewish community. Without much doubt, this was an early find of what later came to be known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. Thank God, this early find didn’t move treasure hunters to ransack the other caves of the area! In any case, as now, scholars were thrilled at the discovery. Timothy responded with all the appropriate questions. He wanted to know what light the find might shed on some passages of Scripture he was curious about. He was eager to discover how the newfound texts compared with the known Hebrew versions of the OT. How did they compare with the Greek Septuagint? Timothy was delighted to hear back that the passages he was concerned about did indeed exist in the ancient manuscripts.

Timothy’s questions are impressive when we compare them to what Western Latin scholars would have made of such a find. They had no idea of the issues Timothy raised. They could not even have read the language of the ancient manuscripts. Only a handful of Western scholars would even have known how to hold the manuscripts: for instance—which way was up and how do you read them, from left to right or vice-versa?

The Church of the East Timothy I led was devoted to both scholarship & missionary activity. While the Latin Church saw the Atlantic Ocean as a wall blocking expansion to the West, the Church of the East saw Asia as a vast region waiting to be evangelized.

The Eastern Church was divided into regions known as Metropolitans. A Metropolitan was like an archbishop, under whom were several bishops, to whom a number of priests & their churches reported. To give you an idea of how vast the church of the East was – Timothy had nineteen metropolitans & eighty-five bishops reporting to him. In the West, England had two archbishops. During Timothy’s tenure as Patriarch, five new metropolitan sees were created near Tehran, in Syria, Turkestan, Armenia, & one on the Caspian Sea. Arabia had at least four bishops & Timothy ordained a new one in Yemen.

Timothy I was to the Church of the East what Gregory I had been to the Western Church in terms of missionary zeal. He commissioned monks to carry the faith from the Caspian Sea all the way to China. He reported the conversion of the great Turkish king, called the khagan, who ruled most of central Asia.

In our next episode, we’ll take a look at the Gospel’s reach into the Far East.

I want to invite you once again to visit us on Facebook – just do a search for The History of the Christian Church, give the page a “like” and leave a comment about where you live.

I also want to thank those subscribers who’ve left a review on iTunes for the podcast. Your comments have been so generous & kind. Thanks much to all. More than anything, it’s those reviews on iTunes that help get the word out about the podcast.

And last, as I engage this revision of Season 1 of CS, new subscribers will hear the revision, but then may get to episodes from the prior version that haven’t been done yet. So, you may hear an occasional remark that CS doesn’t take donations. We didn’t originally and didn’t need to because I was able to absorb the costs personally. As the podcast has grown, I can’t do that anymore and am now taking donations. Seriously, anything helps. So, if you want to donate, go to the sanctorum.us site and use the secure donate feature. Thanks.

by Lance Ralston | Feb 9, 2014 | English |

This episode of Communio Santorum is titled, “And In the East – Part 1.”

The 5th C Church Father Jerome wrote, “[Jesus] was present in all places with Thomas in India, with Peter in Rome, with Paul in Illyria, with Titus in Crete, with Andrew in Greece, with each apostle . . . in his own separate region.”

So far we’ve been following the track of most western studies of history, both secular & religious, by concentrating on what took place in the West & Roman Empire. Even though we’ve delved briefly into the Eastern Roman Empire, as Lars Brownworth aptly reminds us in his outstanding podcast, 12 Byzantine Emperors, even after the West fell in the 5th Century, the Eastern Empire continued to think of & call itself Roman. It’s later historians who refer to it as the Byzantine Empire.

Recently we’ve seen the focus of attention shift to the East with the Christological controversies of the 4th & 5th Cs. In this episode, we’ll stay in the East and follow the track of the expansion of the Faith as it moved Eastward. This is an amazing chapter often neglected in traditional treatments of church history. It’s well captured by Philip Jenkins in his book, The Lost History of Christianity.

We start all the way back at the beginning with the apostle Thomas. He’s linked by pretty solid tradition to the spread of Christianity into the East. In the quote we started with from the early 5th C Church Father Jerome, we learn that the Apostle Thomas carried the Gospel East all the way to India.

In the early 4th C, Eusebius also attributed the expansion of the faith in India to Thomas. Though these traditions do face some dispute, there are still so-called ‘Thomas Christians’ in the southern Indian state of Kerala today. They use an Aramaic form of worship that had to have been transported there very early. A tomb & shrine in honor of Thomas at Mylapore is built of bricks used by a Roman trading colony but was abandoned after ad 50. There’s abundant evidence of several Roman trading colonies along the coast of India, with hundreds of 1st C coins & ample evidence of Jewish communities. Jews were known to be a significant part of Roman trade ventures. Their communities were prime stopping places for the efforts of Christian missionaries as they followed the Apostle Paul’s model as described in the Book of Acts.

A song commemorating Thomas’ role in bringing the faith to India, wasn’t committed to writing till 1601 but was said to have been passed on in Kerala for 50 generations. Many trading vessels sailed to India in the 1st C when the secret of the monsoon winds was finally discovered, so it’s quite possible Thomas did indeed make the journey. Once the monsoons were finally figured out, over 100 trade ships a year crossed from the Red Sea to India.

Jesus told the disciples to take the Gospel to the ends of the Earth. While they were slow to catch on to the need to leave Jerusalem, persecution eventually convinced them to get moving. It’s not hard to imagine Thomas considering a voyage to India as a way to literally fulfill the command of Christ. India would have seemed the end of the Earth.

Thomas’s work in India began in the northwest region of the country. A 4th C work called The Acts of Thomas says that he led a ruler there named Gundafor to faith. That story was rejected by most scholars & critics until an inscription was discovered in 1890 along with some coins which verify the 20-year reign in the 1st C of a King Gundafor.

After planting the church in the North, Thomas traveled by ship to the Malabar Coast in the South. He planted several churches, mainly along the Periyar River. He preached to all classes of people and had about 17,000 converts from all Indian castes. Stone crosses were erected at the places where churches were founded, and they became centers for pilgrimages. Thomas was careful to appoint local leadership for the churches he founded.

He then traveled overland to the Southeast Indian coast & the area around Madras. Another local king and many of his subjects were converted. But the Brahmins, highest of the Indian castes, were concerned the Gospel would undermine a cultural system that was to their advantage, so they convinced the king at Mylapore, to arrest & interrogate him. Thomas was sentenced to death & executed in AD 72. The church in that area then came under persecution and many Christians fled for refuge to Kerala.

A hundred years later, according to both Eusebius & Jerome, a theologian from the great school at Alexandria named Pantaenus, traveled to India to “preach Christ to the Brahmins.”[1]

Serving to confirm Thomas’ work in India is the writing of Bar-Daisan. At the opening of the 3rd Century, he spoke of entire tribes following Jesus in North India who claimed to have been converted by Thomas. They had numerous books and relics to prove it. By AD 226 there were bishops of the Church in the East in northwest India, Afghanistan & Baluchistan, with thousands of laymen and clergy engaging in missionary activity. Such a well-established Christian community means the presence of the Faith there for the previous several decades at the least.

The first church historian, Eusebius of Caesarea, to whom we owe so much of our information about the early Church, attributed to Thomas the spread of the Gospel to the East. As those familiar with the history of the Roman Empire know, the Romans faced continuous grief in the East by one Persian group after another. Their contest with the Parthians & Sassanids is a thing of legend. The buffer zone between the Romans & Persians was called Osrhoene with its capital city of Edessa, located at the border of what today is northern Syria & eastern Turkey. According to Eusebius, Thomas received a request from Abgar, king of Edessa, for healing & responded by sending Thaddaeus, one of the disciples mentioned in Luke 10.[2] Thus, the Gospel took root there. There was a sizeable Jewish community in Edessa from which the Gospel made several converts. Word got back to Israel of the Church community growing in the city & when persecution broke out in the Roman Empire, many refugees made their way East to settle in a place that welcomed them.

Edessa became a center of the Syrian-speaking church which began sending missionaries East into Mesopotamia, North into Persia, Central Asia, then even further eastward. The missionary Mari managed to plant a church in the Persian capital of Ctesiphon, which became a center of missionary outreach in its own right.

By the late 2nd C, Christianity had spread throughout Media, Persia, Parthia, and Bactria. The 2 dozen bishops who oversaw the region carried out their ministry more as itinerant missionaries than by staying in a single city and church. They were what we refer to as tent-makers; earning their way as merchants & craftsmen as they shared the Faith where ever they went.

By AD 280 the churches of Mesopotamia & Persia adopted the title of “Catholic” to acknowledge their unity with the Western church during the last days of persecution by the Roman Emperors. In 424 the Mesopotamian church held a council at the city of Ctesiphon where they elected their first lead bishop to have jurisdiction over the whole Church of the East, including India & Ceylon, known today as Sri Lanka. Ctesiphon was an important point on the East-West trade routes which extended to India, China, Java, & Japan.

The shift of ecclesiastical authority was away from Edessa, which in 216 became a tributary of Rome. The establishment of an independent patriarchate contributed to a more favorable attitude by the Persians, who no longer had to fear an alliance with the hated Romans.

To the west of Persia was the ancient kingdom of Armenia, which had been a political football between the Persians & Romans for generations. Both the Persians & Romans used Armenia as a place to try out new diplomatic maneuvers with each other. The poor Armenians just wanted to be left alone, but that was not to be, given their location between the two empires. Armenia has the historical distinction of being the first state to embrace Christianity as a national religion, even before the conversion of Constantine the Great in the early 4th C.

The one who brought the Gospel to Armenia was a member of the royal family named Gregory, called “the Illuminator.” While still a boy, Gregory’s family was exiled from Armenia to Cappadocia when his father was thought to have been part of a plot to assassinate the King. As a grown man who’d become a Christian, Gregory returned to Armenia where he shared the Faith with King Tiridates who ruled at the dawn of the 4th C. Tiridates was converted & Gregory’s son succeeded him as bishop of the new Armenian church. This son attended the Council of Nicea in 325. Armenian Christianity has remained a distinctive and important brand of the Faith, with 5 million still professing allegiance to the Armenian Church.[3]

Though persecution came to an official end in the Roman Empire with Constantine’s Edict of Toleration in 313, it BEGAN for the church in Persia in 340. The primary cause for persecution was political. When Rome became Christian, its old enemy turned anti-Christian. Up to that point, the situation had been reversed. For the first 300 hundred years, it was in the West Christians were persecuted & Persia was a refuge. The Parthians were religiously tolerant while their less tolerant Sassanid successors were too busy fighting Rome to waste time or effort on the Christians among them.

But in 315 a letter from Constantine to his Persian counterpart Shapur II triggered the beginnings of an ominous change in the Persian attitude toward Christians. Constantine believed he was writing to help his fellow believers in Persia but succeeded only in exposing them. He wrote to the young Persian ruler: “I rejoice to hear that the fairest provinces of Persia are adorned with Christians. Since you are so powerful and pious, I commend them to your care, and leave them in your protection.”

The schemes & intrigues that had flowed for generations between Rome & the Persians were so intense this letter moved Shapur to become suspicious the Christians were a kind of 5th column, working from inside the Empire to bring the Sassanids down. Any doubts were dispelled 20 years later when Constantine gathered his forces in the East for war. Eusebius says Roman bishops accompanied the army into battle. To make matters worse, in Persia, one of their own preachers predicted Rome would defeat the Sassanids.

Little wonder then, when persecution began shortly after, the first accusation brought against Christians was that they aided the enemy. Shapur ordered a double taxation on Christians & held their bishop responsible for collecting it. Shapur knew Christians tended to be poor since so many had come from the West fleeing persecution, so the bishop would be hard-pressed to come up w/the money. But Bishop Simon refused to be intimidated. He declared the tax unjust and said, “I’m no tax collector! I’m a shepherd of the Lord’s flock.” Shapur counter-declared the church was in rebellion & the killings began.

A 2nd decree ordered the destruction of churches and the execution of clergy who refused to participate in the official Sassanid-sponsored sun-worship. Bishop Simon was seized & brought before Shapur. Offered a huge bribe to capitulate, he refused. The Persians promised if he alone would renounce Christ, the rest of the Christian community wouldn’t be harmed, but that if he refused he’d be condemning all Christians to destruction. When the Christians heard of this, they rose up, protesting en masse that this was shameful. So Bishop Simon & a large number of the clergy were executed.

For the next 20 years, Christians were hunted down from one end of Persia to the other. At times it was a general massacre. But more often it was organized elimination of the church’s leaders.

Another form of suppression was the search for that part of the Christian community that was most vulnerable to persecution; Persians who’d converted from Zoroastrianism. The faith spread first among non-Persians in the population, especially Jews & Syrians. But by the beginning of the 4th C, Persians in increasing numbers were attracted to the Christian faith. For such converts, church membership often meant the loss of everything – family, property rights, even life.

The martyrdom of Bishop Simon and the years of persecution that followed gutted the Persian church of its leadership & organization. As soon as the Christians of Ctesiphon elected a new bishop, he was seized & killed. Adding to the anti-Roman motivation of the government’s role in the persecutions was a deep undercurrent of Zoroastrian fanaticism that came as a result of the conversion of so many of their number to Christianity; it was a shocking example of religious envy.

Shortly before Shapur II’s death in 379, persecution slackened. It had lasted for 40 years and only ended with his death. When at last the suffering ceased, it’s estimated close to 200,000 Persian Christians had been put to death.

[1] Yates, T. (2004). The expansion of Christianity. Lion Histories Series (28–29). Oxford, England: Lion Publishing.

[2] Yates, T. (2004). The expansion of Christianity. Lion Histories Series (24). Oxford, England: Lion Publishing.

[3] Yates, T. (2004). The expansion of Christianity. Lion Histories Series (25). Oxford, England: Lion Publishing.

by Lance Ralston | Feb 2, 2014 | English |

The title of this episode is, “Can’t We All Just Get Along?”

In our last episode, we began our look at how the Church of the 4th & 5th Cs attempted to describe the Incarnation. Once the Council of Nicaea affirmed Jesus’ deity, along with His humanity, Church leaders were left with the task of finding just the right words to describe WHO Jesus was. If He was both God & Man as The Nicaean Creed said, how did these two natures relate to one another?

We looked at how the churches at Alexandria & Antioch differed in their approaches to understanding & teaching the Bible. Though Alexandria was recognized as a center of scholarship, the church at Antioch kept producing church leaders who were drafted to fill the role of lead bishop at Constantinople, the political center of the Eastern Empire. While Rome was the undisputed lead church in the West, Alexandria, Antioch & Constantinople vied with each other over who would take the lead in the East. But the real contest was between Alexandria in Egypt & Antioch in Syria.

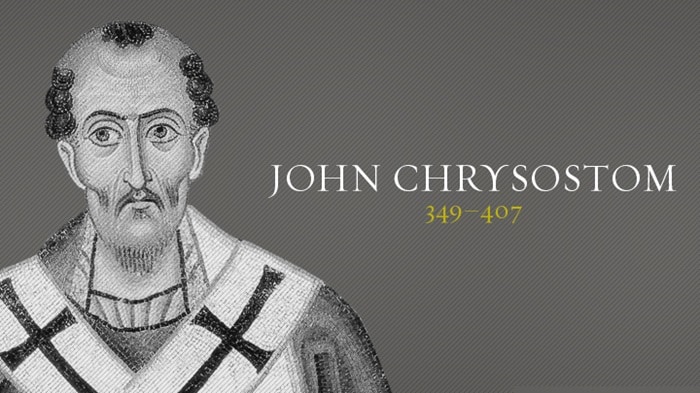

The contest between the two cities & their churches became clear during the time of John Chrysostom from Antioch & Theophilus, lead bishop at Alexandria. Because of John’s reputation as a premier preacher, he was drafted to become Bishop at Constantinople. But John’s criticisms of the decadence of the wealthy, along with his refusal to tone down his chastisement of the Empress, caused him to fall out of favor. I guess you can be a great preacher, just so long as you don’t turn your skill against people in power. Theophilus was jealous of Chrysostom’s promotion from Antioch to the capital and used the political disfavor growing against him to call a synod at which John was disposed from office as Patriarch of Constantinople.

That was like Round 1 of the sparring match between Alexandria and Antioch. Round 2 and the deciding round came next in the contest between 2 men; Cyril & Nestorius.

Cyril was Theophilus’ nephew & attended his uncle at the Synod of the Oak at which Chrysostom was condemned. Cyril learned his lessons well and applied them with even greater ferocity in taking down his opponent, Nestorius.

Before we move on with these 2, I need to back-track some & bore the bejeebers out of you for a bit.

Warning: Long, hard to pronounce, utterly forgettable word Alert.

Remember è The big theological issue at the forefront of everyone’s mind during this time was how to understand Jesus.

Okay, we got it: à

The Nicaean Creed’s been accepted as basic Christian doctrine.

The Cappadocian Fathers have given us the right formula for understanding the Trinity.

There’s 1 God in 3 persons; Father, Son & Holy Spirit.

Now, on to the next thing: Jesus is God and Man. How does that work? Is He 2 persons or 1? Does He have 1 nature or 2? And if 2, how do those natures relate to one another?

A couple ideas were floated to resolve the issue but came up short; Apollinarianism and Eutychianism.

Apollinaris of Laodicea lived in the 4th C. A defender of the Nicene Creed, he said in Jesus the divine Logos replaced His human soul. Jesus had a human body in which dwelled a divine spirit. Our longtime friend Athanasius led the synod of Alexandria in 362 to condemn this view but didn’t specifically name Apollinaris. 20 Yrs later, the Council of Constantinople did just that. Gregory of Nazianzus supplied the decisive argument against Apollinarianism saying, “What was not assumed was not healed” meaning, for the entire of body, soul, and spirit of a person to be saved, Jesus Christ must have taken on a complete human nature.

Eutyches was a, how to describe him; elderly-elder, a senior leader, an aged-monk in Constantinople who advocated one nature for Jesus. Eutychianism said that while in the Incarnation Jesus was both God & man, His divine nature totally overwhelmed his human nature, like a drop of vinegar is lost in the sea.

Those who maintained the dual-nature of Jesus as wholly God and wholly Man are called dyophysites. Those advocating a single-nature are called Monophysites.

What happened between Cyril & Nestorius is this . . .

Nestorius was an elder and head of a monastery in Antioch when the emperor Theodosius II chose him to be Bishop of Constantinople in 428.

Now, what I’m about to say some will find hard to swallow, but while Nestorius’s name became associated with one of the major heresies to split the church, the error he’s accused of he most likely wasn’t guilty of. What Nestorius was guilty of was being a jerk. His story is typical for several of the men who were picked to lead the church at Constantinople during the 4th through 7th Cs; effective preachers but lousy administrators & seriously lacking in people skills. Look, if you’re going to be pegged to lead the Church at the Political center of the Empire, you better be a savvy political operator, as well as a man of moral & ethical excellence. A heavy dose of tact ought to have been a pre-requisite. But guys kept getting selected who came to the Capital on a campaign to clean house. And many of them seem to have thought subtlety was the devil’s tool.

As soon as Nestorius arrived in Constantinople, he started a harsh campaign against heretics, meaning anyone with whom he disagreed. It wouldn’t take long before his enemies accused him of the very thing he accused others of. But in their case, their accusations were born of jealousy.

Where they deiced to take offense was when Nestorius balked at the use of the word Theotokos. The word means God-bearer, and was used by the church at Alexandria for the mother of Jesus. While the Alexandrians said they rejected Apollinarianism, they, in fact, emphasized the divine nature of Jesus, saying it overwhelmed His human nature. The Alexandrian bishop, Cyril, was once again jealous of the Antiochan Nestorius’ selection as bishop for the Capital. As his uncle Theophilus had taken advantage of Chrysostom’s disfavor to get him deposed, Cyril laid plans for removing the tactless & increasingly unpopular Nestorius. The battle over the word Theotokos became the flashpoint of controversy, the crack Cyril needed to pry Nestorius from his position.

To supporters of the Alexandrian theology, Theotokos seemed entirely appropriate for Mary. They said she DID bear God when Jesus took flesh in her womb. And to deny it was to deny the deity of Christ!

Nestorius and his many supporters were concerned the title “Theotokos” made Mary a goddess. Nestorius maintained that Mary was the mother of the man Who was united with the divine Logos, and nothing should be said that might imply she was the “Mother à of God.” Nestorius preferred the title Christokos; Mary was the Christ-bearer. But he lacked a vocabulary and the theological sophistication to relate the divine and human natures of Jesus in a convincing way.

Cyril, on the other hand, argued convincingly for his position from the Scriptures. In 429, Cyril defended the term Theotokos. His key text was John 1: 14, “The Word became flesh.” I’d love to launch into a detailed description of the nuanced debate between Cyril and Nestorius over the nature of Christ but it would leave most, including myself, no more clued in than we are now.

Suffice it to say, Nestorius maintained the dual-nature-in-the-one-person of Christ while Cyril stuck to the traditional Alexandrian line and said while Jesus was technically 2 natures, human & divine, the divine overwhelmed the human so that He effectively operated as God in a physical body.

Where this came down to a heated debate was over the question of whether or not Jesus really suffered in His passion. Nestorius said that the MAN Jesus suffered but not His divine nature, while Cyril said the divine nature did indeed suffer.

When the Roman Bishop Celestine learned of the dispute between Cyril and Nestorius, he selected a churchman named John Cassian to respond to Nestorius. He did so in his work titled On the Incarnation in 430. Cassian sided with Cyril but wanted to bring Nestorius back into harmony. Setting aside Cassian’s hope to bring Nestorius into his conception of orthodoxy, Celestine entered a union with Cyril against Nestorius and the church at Antioch he’d come from. A synod at Rome in 430 condemned Nestorius, and Celestine asked Cyril to conduct proceedings against him.

Cyril condemned Nestorius at a Synod in Alexandria and sent him a notice with a cover letter listing 12 anathemas against Nestorius and anyone else who disagreed with the Alexandrian position. For example à “If anyone does not confess Emmanuel to be very God, and does not acknowledge the Holy Virgin to be Theotokos, for she brought forth after the flesh the Word of God become flesh, let him be anathema.”

Receiving the letter from Cyril, Nestorius humbly resigned and left for a quiet retirement at Leisure Village in Illyrium. à Uh, not quite. True to form, Nestorius ignored the Synod’s verdict.

Emperor Theodosius II called a general council to meet at Ephesus in 431. This Council is sometimes called the Robber’s Synod because it turned into a bloody romp by Cyril’s supporters. As the bishops gathered in Ephesus, it quickly became evident the Council was far more concerned with politics than theology. This wasn’t going to be a sedate debate over texts, words & grammar. It was going to be a physical contest. Let’s settle doctrinal disputes with clubs instead of books.

Cyril and his posse of club-wielding Egyptian monks, and I use the word posse purposefully, had the support of the Ephesian bishop, Memnon, along with the majority of the bishops from Asia. The council began on June 22, 431, with 153 bishops present. 40 more later gave their assent to the findings. Cyril presided. Nestorius was ordered to attend but knew it was a rigged affair and refused to show. He was deposed and excommunicated. Ephesus rejoiced.

On June 26, John, bishop of Antioch, along with the Syrian bishops, all of whom had been delayed, finally arrived. John held a rival council consisting of 43 bishops and the Emperor’s representative. They declared Cyril & Memnon deposed. Further sessions of rival councils added to the number of excommunications.

A report reached Theodosius II, and representatives of both sides pled their case. Theodosius’s first instinct was to confirm the depositions of Cyril, Memnon, & Nestorius. Be done with the lot of them. But a lavish gift from Cyril persuaded the Emperor to dissolve the Council and send Nestorius into exile. A new bishop for Constantinople was consecrated. Cyril returned in triumph to Alexandria.

From a historical perspective, it’s what happened AFTER the Council of Ephesus that was far more important. John of Antioch sent a representative to Alexandria with a compromise creed. This asserted the duality of natures, in contrast to Cyril’s formulation, but accepted the Theotokos, in contrast to Nestorius. This compromise anticipated decisions to be reached at the next general church Council at Chalcedon.

Cyril agreed to the creed and a reunion of the churches took place in 433. Since then, historians have asked if Cyril was being a statesman in agreeing to the compromise or did he just cynically accept it because he’d achieved his real purpose; getting rid of Nestorius. Either way, the real loser was Nestorius. Theodosius had his books burned, and many who agreed with Nestorius’s theology dropped their support.

Those who represented his theological emphases continued to carry on their work in eastern Syria, becoming what History calls the Church of the East, a movement of the Gospel we’ll soon see that reached all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

While in exile, Nestorius wrote a book that set forth the story of his life and defended his position. Modern reviews of Nestorius find him to be more of a schismatic in temperament than a heretic. He denied the heresy of which he was accused, that the human Jesus and the divine Christ were 2 different persons.

20 yrs after the Council of Ephesus, which many regarded as a grave mistake, another was called at Chalcedon. Nestorius’ teaching was declared heretical and he was officially deposed. Though already in exile, he was now banished by an act of the Church rather than Emperor. In one of those odd facts of history, though what Nestorius taught about Christ was declaimed, it turned out to be the position adopted by the Creed that came out of the Council of Chalcedon. When word reached Nestorius in exile of the Council’s finding he said they’d only ratified what he’d always believed & taught.

There’s much to learn from this story of conflict and resolution.

First, many of the doctrines we take for granted as being part and parcel of the orthodox Christian faith, came about through great struggle and debate of some of the most brilliant minds history’s known. Sometimes, those ideas were popular and ruled because they were expedient. But mere politics can’t sustain a false idea. There are always faithful men and women who love truth because it’s true, not because it will gain them power, influence or advantage. They may suffer at the hands of the corrupt for a season, but they always prevail in the end.

We ought to be thankful, not only to God for giving us the truth in His Word and the Spirit to understand it, but also to the people who at great cost were willing to hazard themselves to make sure Truth prevailed over error.

Second, Too often, people look back on the “Early Church” and assume it was a wonderful time of sweet harmony. Life was simple, everyone agreed and no one ever argued. Hardly!

Good grief. Have they read the Bible? The disciples were forever arguing over who was greatest. Paul & Barnabas had a falling out over John Mark. Paul had to get in Peter’s face when he played the hypocrite.

Yes, for sure, in Acts we read about a brief period of time when the love of the fellowship was so outstanding it shook the people of Jerusalem to the core and resulted in many coming to faith. But that was only a brief moment that soon passed.

God wants His people to be in unity. True unity, under the truth of the Gospel, is an incredibly powerful proof of our Faith. But the idea that the Early Church was a Golden Age of Unity is a fiction. Philip Jenkins’ book on the battle over the Christology of the 4th & 5th Cs. is titled Jesus Wars.

The Church as a whole would be better served today in its pursuit of unity if each local congregation focused its primary efforts on loving and serving one another through the power of the Spirit. It’s inevitable if they excelled at that, they’d begin looking at all churches and believers in the same way, and unity would be real rather than a program with a start & end date or a campaign based on personalities and hype.

Hey – come to think of it, that’s what DID bring about that short glorious moment of blissful harmony in Jerusalem among the followers of Jesus – they loved and served one another in the power of the Spirit.

by Lance Ralston | Jan 26, 2014 | English |

This episode is titled “Who Do You Say He Is?”

We begin this episode by reading from the Chalcedonian Creed of AD 451, the portion devoted to the orthodox view of Christ.

We, then, following the holy Fathers, all with one consent, teach men to confess one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, the same perfect in Godhead and also perfect in manhood; truly God and truly man, of a rational soul and body; consubstantial with the Father according to the Godhead, and consubstantial with us according to the Manhood; in all things like unto us, without sin; begotten before all ages of the Father according to the Godhead, and in these latter days, for us and for our salvation, born of the Virgin Mary, the Mother of God, according to the Manhood; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, only begotten, to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably; the distinction of natures being by no means taken away by the union, but rather the property of each nature being preserved, and concurring in one Person and one Subsistence, not parted or divided into two persons, but one and the same Son, and only begotten, God the Word, the Lord Jesus Christ; as the prophets from the beginning declared concerning Him, and the Lord Jesus Christ Himself has taught us, and the Creed of the holy Fathers has handed down to us.

Compare that to the simple words of the Apostles Creed quoted by many Christians from memory 300 years before.

I believe in . . . Jesus Christ, God’s only begotten Son, our Lord: Who was conceived by the Holy Ghost, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate; was crucified, dead and buried. He descended into hell. The third day he rose again from the dead. He ascended into heaven and sits at the right hand of God the Father Almighty. From thence he shall come to judge the living and the dead.

Quite a difference. What caused the Church to draw such exacting language regarding who Jesus was between the early 2nd & mid 5th Cs? That’s the subject of this and the next episode. Along the way, we’ll see of interesting developments in the Church and learn of some colorful characters.

In the 16th chapter of Matthew’s Gospel, we read of a time near Caesarea Philippi in Galilee when Jesus asked His disciples, “Who do people think I am?” After hearing what the popular talk was, Jesus asked them “Who do YOU say I am?” That set the stage for Peter to confess his faith in Jesus as Messiah.

We might think Jesus’ affirmation of Peter’s reply would put an end to the controversy. It was only the beginning. That controversy raged over the next 500 yrs as Church leaders wrestled with HOW to understand Jesus.

We’ve already touched on this subject in previous episodes. I’ve mentioned we’d return to deal with it specifically in a future episode. This is it; and here’s why we need to slow down a bit and take our time reviewing the history of the controversy over how to understand Who Jesus was. We need to camp here for a bit because this issue consumed a good amount of the Church’s intellectual energy during the 4th & 5th Cs.

Today, we accept the orthodox view of the Trinity & the Nature of Jesus as God and Man readily; not realizing the agony the Early Church Fathers endured while they labored over precisely HOW to put into just the right words what Christians believe. One theologian said Theology is the fine art of making distinctions. Nowhere is that more clear than here; in our examination of how orthodox theologians described a Christ.

The first great Ecumenical Council was held at Nicaea in 325 at the urging of the Emperor Constantine. Some 300 bishops representing the entire Christian world attended to hammer out their response to Arianism; the idea that Jesus was human, but not divine. As the Council dragged on, Constantine, itching to get back to the business of running the Empire, pressed the bishops to adopt a Statement that affirmed Jesus was both God & man. But many of the bishops left Nicaea discontented with the wording of the Nicaean Creed. They felt it was imprecise. It failed to capture the full truth of Who Jesus is. This lack of support for the Nicaean Creed opened the doors for many of the later controversies that would wrack the Church. The Council of Chalcedon 125 yrs later tightened up the language on Nicaea but didn’t fundamentally alter the Creed. Let’s take a look at the time between Nicaea & Chalcedon . . .

Sometimes, in an attempt to bring clarity to a complex situation, we over-simplify. I run the risk of doing that here. But for the sake of brevity, I beg the listeners’ indulgence as I chart the path from 325 to 451.

Following Nicaea, with the affirmation that Jesus is both God & Man, the Church had to first harmonize that with the Biblical reality there’s ONE God, not Two. And wait, someone asked, what about the Holy Spirit; doesn’t the Bible says He’s also God? The classic, orthodox statement of the Trinity, that God is 1 in substance or essence, but 3 in persons wasn’t something everyone immediately agreed to. It wasn’t like at the Council of Nicaea they took a vote and agreed Jesus is both deity & humanity. Then someone raised their hand & said, “Isn’t there just one God?”

Yes. à Well, how do we describe God now? They waited in silence for 14 seconds, then someone said, “How about this: We’ll say God is one in substance & 3 in person.” They all smiled & nodded, slapped that guy on the back and said, “Good one. There it is; the Trinity! Our work here is done. Let’s go for pizza. I get shotgun.”

No; it took a while to get the wording right. What made it difficult is that they were working in 2 languages, Greek & Latin. A formulation that seemed to work in Greek was hard to bring over into Latin, and vice versa.

It took the work of the Cappadocian Fathers, Basil the Great of Caesarea, his younger brother Gregory of Nyssa, and their close friend Gregory of Nazianzus who worked out the wording that satisfied most of the bishops and framed the classic, orthodox doctrine of the Trinity. The Council of Constantinople was called in 381 to make this Trinitarian formulation official. This was just a year after Emperor Theodosius I declared Christianity the official State religion.

So, with that piece of important theological business out of the way, they moved on to the next topic. And this is where it gets messy.

If Jesus is both God & Man – how are we to understand that? Does He have 2 natures, or does 1 of the natures trump the other? Or is there a 3rd way: Did the human & divine natures fuse into a new, hybrid nature? And if Jesus IS a hybrid, do Christians get to drive in the chariot-pool lane?

Lots of different camps put forward their scheme and fought hard to see their doctrinal formulation become the official position of the Church.

The Council of Ephesus in 431 came out with a position that elevated 1 nature, while the Council at Chalcedon 20 years later altered that by affirming Jesus’s 2 natures.

It became obvious to church leaders after the Council at Constantinople that the turmoil they saved in solving the problem of the Trinity was just added to the Christological problem that rose next.

To understand how this issue was settled, we need to take a look at the rivalry that grew between 2 churches; a rivalry sparked in large part by Christianity being liberated from persecution and elevated to the darling of the State. Those 2 churches were Alexandria & Antioch.

The debate over how to understand the Person & Natures of Jesus was staged in the Eastern Empire. The West wasn’t as involved because Rome simply did not see as much challenge on its belief in the dual nature of Christ. So while it wasn’t the scene of so much theological turmoil, it did play an important part in how the controversy was settled.

Political rivalry between Alexandria and Antioch had been going on for some time. Being in the East, both churches vied with each other to provide Bishops to Constantinople, the New Rome & political center of the Eastern Empire. Getting one of their Bishops promoted to the capital meant bragging rights and could result in additional power & prestige for the Alexandrian or Antiochan sees. Two bishops from Antioch that were drafted by Constantinople were John Chrysostom, who we’ve already looked at, and Nestorius, who we will.

In addition to their ecclesiastical jealousy, was the very different cultural and theological traditions in play at Antioch and Alexandria. The church at Antioch had a closer tie to the Jewish roots in Jerusalem. It had a stronger tradition of rational inquiry. It was at Antioch that church leaders had dug deeply in the OT to find many of the great types that pointed to Jesus. They studied Scripture through the lens of literal interpretation, rejoicing that God became Man in the Person of Jesus.

The Church at Alexandria was different. It grew up under the influence of philosophical Judaism as seen in Philo and passed on to scholars like Clement & Origen. The Alexandrians had a tradition of contemplative piety, as we might expect from a church near the Egyptian desert where the hermits got their start and had been such stand-out heroes of the Faith for generations. In interpreting Scripture, the Church at Alexandria developed and was devoted to the allegorical method. This saw the truest meaning of Scripture to be the spiritual realities hidden in its literal, historical words.

While the leaders at Antioch saw Jesus as God come as man, at Alexandria they agreed Jesus was a man, but His divine nature utterly overwhelmed the human so that He effective had only 1 operative nature; the divine.

The differences between Antioch and Alexandria had already surfaced in their different approaches in refuting the error of Arianism. That they never reconciled them set the stage for all the acrimony to ensue over the debate on Jesus. The Arians made much of the NT passages that seemed to suggest Jesus’ subordination to God the Father. They liked to quote John 14: 28, where Jesus said, “the Father is greater than I,” & Matt 24: 36, “No one knows . . . not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father.” In reply to the Arians, the theologians at Alexandria argued such passages were properly applied to the Son of God in his incarnation. The theologians of Antioch took a different route, referring such passages not to Jesus divinity, but to his humanity. That may seem like splitting semantic hairs; I say poh-tay-toe; You say poh–tah-toe – but our friends in Antioch and Alexandria thought it a big deal and major difference. Really, both approaches provided a defense of the Nicene theology, a refutation of Arianism, and a framework for interpreting the Gospels.

This is where I need to simplify lest we get into the minutiae of theologians with too much parchment, ink and time. In summary, the Alexandrian approach recognized Jesus as God but tended to diminish His humanity. The Antiochan approach readily embraced Jesus’ humanity but had a hard time explaining how His human and divine natures related to each other.

Let me try to make this more practical; maybe something you’ve grappled with. Have you ever pondered how Jesus could be tempted in all points as we are, as it says in Heb 4:15, yet as God, it was impossible for Him to sin? Sometimes you’ll hear it put this way; Was Jesus REALLY tempted, since as God, He COULDN’T sin? As a man, he had the potential to sin. But as God, He couldn’t. So was His experience of humanity genuine? If you can relate to the quandary those questions pose, you get an idea of the challenge the Antiochans faced.

The difference between Antioch and Alexandria on how to understand Jesus was why Arianism & the Nicene Creed kept coming up in the Christological controversies dominating the 4th & 5th Centuries. Each side thought the other was selling out to Arianism.

The battle between the 2 churches came to a head in the 5th C in the war that took place between 2 men; Bishop Cyril of Alexandria and Bishop Nestorius of Antioch who became Bishop of Constantinople.

But that’s the subject for our next episode.

by Lance Ralston | Jan 19, 2014 | English |

This Episode is simply titled “Leo”

While there’d been several bishops of the church at Rome who’d been capable leaders and under their guidance had established Rome as the premier church, if not the whole Christian world, at least in the western portion of the now declining Roman Empire, it can be fairly said that for most of the earlier bishops the person was eclipsed by the office. Bishops Callistus, Stephen, Damasus, & Innocent I all added significant authority to the Roman See. But it was Leo the Great who saw the Bishop of Rome become what we might call the first real Pope. It was with Leo I that the idea of the Papacy became real.

While previous bishops at Rome had certainly been theologically astute, as befitted their office, Leo can be classed as a first-rate theologian, arguably the greatest theologian of any who came before in that office and for a century & a half after. He battled the Manichæan, Priscillianist, & Pelagian heresies, and won enduring fame for helping to finish codifying the orthodox doctrine of the person of Christ.

Leo’s early life is shrouded in mystery. The chief source of information about him comes from his letters & they don’t commence till AD 442 when he was already an adult. Leo was mostly likely a Roman who became a deacon, then a legate under Bishops Celestine I & Sixtus III. A legate is a special messenger, sent by a bishop, to carry messages to civil rulers. Think à Church ambassador to the king. Leo was so astute in his task as a representative for the Church, Emperor Valentinian III sent him on a special mission to settle a dispute in Gaul between a couple feuding generals. This was at a time of great turmoil in the north due to the barbarian threat. While Leo was on this peace-making mission, Bishop Sixtus died and Leo was chosen to take his seat. He served for the next 21 years.

Leo describes his feelings at the assumption of his office in a sermon;

“Lord, I have heard your voice calling me, and I was afraid: I considered the work which was enjoined on me, and I trembled. For what proportion is there between the burden assigned to me and my weakness, this elevation and my nothingness? What is more to be feared than exaltation without merit, the exercise of the most holy functions being entrusted to one who is buried in sin? Oh, you have laid upon me this heavy burden, bear it with me, I beseech you be you my guide and my support.”

Leo’s papacy faced 2 immense problems.

First: The emergence of heresies threatened the integrity of the Church; and à

Second: The political disintegration of the Western Roman Empire.

Leo offered 3 tactics in dealing with these difficulties à

1) Actions to provide essential church doctrine with a clear, orthodox position;

2) Efforts to unify church government under a sovereign papacy; and

3) Attempts at peace by negotiating with the Empire’s enemies.

On the doctrinal front, Leo theologically refuted the era’s main heresies & utilized imperial criminal prosecution & banishment to get rid of unrepentant heretics. Leo’s finest achievement was probably the formation and acceptance of an orthodox Christological dogma.

Though Arianism was in retreat, the 5th C battled with what’s called Eutychianism. We’re going to get into this in more depth in a soon coming episode so for now let me just say that Eutychianism was one of the 4th & 5th Cs’ attempts to understand the nature of Jesus. Was He God, Man or both? And if both, how do the 2 nature relate to each other? Eutychianism said Jesus had 2 natures, human & divine, but that the divine had completely dominated the human, like a drop of vinegar is overwhelmed by the sea. Later it will come to be known by a label you may have heard = Monophysitism.

Leo’s manner of dealing with this aberrant teaching was brilliant. Rather than rely on suppression, he brought it’s main advocate, Eutychus, to Rome for lengthy discussions and, after painstaking research & deliberation, issued a carefully written letter, the famous Tome of Leo. It set forth a clear exposition of Christ’s 2 natures in 1 person & became the basis in 451 for the Council of Chalcedon’s enduring formulation of Christological doctrine.

This alone would mark Leo as worthy of the honorific “Great” but he did more, much more. He rescued the city of Rome from destruction, not once, but twice! When Attila & his Huns, known as the “Scourge of God,” destroyed the Italian city of Aquileia in 452 & everyone knew Rome was next on the barbarian’s hit list, Leo, with a couple companions, travelled north, entered the hostile camp, and persuaded Attila to leave off sacking the City. Think of it; a bishop’s simple word accomplished what the waning might of the once mighty Rome could not, convince the barbarian hordes to go home.

Then, 3 yrs later when the Vandal king Genseric was poised to do what Attila had been deflected from, Leo was able to obtained a promise the Vandals would relieve the city of its wealth but not burn it or slay its people. The sacking lasted for 2 wks – but when the looters finally left, the city still stood and its citizenry, though badly shaken were still alive; and eternally grateful for Leo’s intervention.

He died in 461, and was buried in the Church of St. Peter.

The literary works of Leo consist of nearly a hundred sermons and over 170 letters. His collection of sermons is the first we have from a Roman bishop. He declared preaching to be his sacred duty. His sermons were short and simple.

Leo was a man of extraordinary activity. He took a leading part in all the affairs of the Church. While his private life is unknown, there’s not a hint of anything that would give us cause to think he was anything other than pure in both motive & morals. His zeal, time & strength were all devoted to the interests of the Faith. If Leo saw the Faith primarily through the lens of the life & outreach of the Church at Rome, we ought to attribute that to his conviction Rome was meant by God to be THE Home Base for the Church; its headquarters.

As Church historian Philip Schaff said, Leo was animated by an unwavering conviction God had committed to him, as the successor of Peter, the care of the whole Church. He anticipated all the dogmatic arguments by which the power of the papacy was later established. Leo made the case that the rock on which the Church is built, mentioned by Jesus in Matthew 16, meant Peter and his confession of faith, that set the cornerstone for THE Faith. Leo claimed that while Christ himself is in the highest sense the Rock and Foundation of the Church, His authority was transferred primarily to Peter. To Peter specifically, Christ entrusted the apostolic keys of the Kingdom. Also, Jesus’ prayer that Peter be strengthened so he might strengthen others established Peter’s role as leader among the Apostles. Jesus’ post-resurrection affirmation of Peter’s call, “Feed my sheep,” makes Peter the pastor and prince of the Church Entire, through whom Christ exercises His universal dominion on Earth.

But Leo went further, He said Peter’s primacy wasn’t limited to the apostolic age; it endured in those subsequent bishops of Rome to whom Peter passed the authority Jesus endowed him with. Leo asserted only Rome could serve as the center of the Church because it was both a political & religious center. Sure, Constantinople was political headquarters but it lacked Rome’s spiritual ancestry. Alexandria & Antioch were religious, but not political centers. Only Rome provided a sufficient political and spiritual weight to be the center of the Earthly manifestation of the Kingdom of God.

While Leo made much of Rome’s place as premier among the churches, he himself remained humble. This personal humility was offset by his determination others would honor his office as though he were indeed a modern Peter. Each year a special celebration was called to commemorate his ascension to Peter’s seat. He took such confusing titles as, “Servant of the servants of God,” “vicar of Christ,” and even “God upon earth.”

As an aside, if you’ve read my bio on the sanctorum.us site, you know I’m a non-denominational, Evangelical, follower of Jesus. As I’ve shared in a previous podcast, it’s been interesting reading reviews by listeners that I’m obviously è Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Reformed, Pentecostal, & a few other flavors of the faith. I guess people mistake what my personal view is because I’m trying, albeit haltingly, to treat the material in as fair & unbiased a fashion as possible. So, I suspect here’s what’s happening in a lot of listeners minds right now after sharing Leo the Great’s apologetic for the primacy of Peter; they’re wondering if I’ve gone RC!

Let me respond to that by sharing this . . .

While Leo did make a good case for the Bishop at Rome being the spiritual successor to Peter, what about the fact that Peter himself passes over his primacy in silence. In his NT letters he expressly warned against hierarchical assumptions while Leo used every opportunity to affirm his authority. In Antioch, when Peter played the role of hypocrite, he meekly submitted to the junior apostle Paul’s rebuke. Leo, on the other hand, declared any resistance to his authority as an impious pride and sure way to hell. Under Leo, obedience to the pope was a condition to salvation. He claimed anyone not in harmony with Rome’s See as the head of the body, from which all gifts of grace descended, was in fact not IN The Church, and so had no part in grace or the Body of Chrsit.

Schaff wrote,

This is the fearful but legitimate logic of the papal principle, which confines the kingdom of God to the narrow lines of a particular organization, and makes the universal spiritual reign of Christ dependent on a temporal form and a human organ.

Another important point: Crucial to the idea that the Bishop of Rome was & is the spiritual heir to Peter’s apostolic authority is the assumption Peter founded & led the Church at Rome. There’s simply not a shred of evidence for that. Sure, Peter went to Rome, but besides being buried there, there’s no evidence he ever functioned as the leader of fellowship there. The assumption that he must have been because he was an Apostle would be like assuming if Billy Graham visited your city and attended your church for a few weeks, he was THE pastor – and later pastors could then claim they operated in the authority & ministry of Billy Graham.

In carrying his idea of the Papacy into effect, Leo displayed a cunning diplomacy & consistency that characterized some of the popes of the Middle Ages. Certainly, the circumstances of the times were in his favor. This was the era of the fall of the Western Empire. The East was being torn apart by doctrinal controversies we’ll look at in a later episode. Africa was over-run by barbarians. The West was without political leadership, and there were no strong church leaders of the flavor of an Athanasius or Jerome to lead.

Leo took advantage of the Arian Vandals rampaging across North African, giving rise to the word that memorializes their career – Vandal, to write the bishops there in the tone of an over-shepherd. They eagerly submitted to his authority in AD 443. He banished the last of the heretical Manichæans & Pelagians from Italy. Then in 444 Leo looked Eastward & began affirming Bishops to key posts, increasingly encroaching on territory that had been under the purview of Constantinople, Alexandria & Antioch. But Leo reserved to himself a right of appeal by lower bishops in important cases; things which ought to be decided by the pope according to divine revelation.

We’ll learn a little more about Pope Leo I, called Leo the Great in future episodes as he played a key role in the Church life of the 5th C.

As we end this episode, I want to again invite you to stop by the sanctorum.us website for more info about the podcast, and to visit the Facebook page to give us a like. Do a search for Communio Sanctorum – History of the Christian Church. Leave a comment and tell us where you live. It’s been fun seeing all the places our subscribers hail from.

Till next time . . .

by Lance Ralston | Jan 19, 2014 | English |

This episode is titled – “The New Center.”

Spread over 3 pages in Vol. 3 of his monumental work History of the Christian Church, author Philip Schaff makes a compelling argument for why it was inevitable Christianity would eventually emerge from the Roman catacombs to join the State in governing the hearts & lives of the people of the Empire. And while it was inevitable, Schaff describes how the merger resulted in the corruption of the Church. He wrote, “The Christianizing of the State amounted in great measure to the paganizing and secularizing of the Church.”

We’ve already seen how the Church at Rome emerged to become a headquarters of Western Christianity. We need to spend a little more time here as this period of church history is crucial for understanding the eventual rift that occurred between East and West and what emerged in Europe after this, not only for the Church but for the nations that arose there.

The idea of the rule of the entire Church by the Roman Pope was a slow and halting process. The title “Pope / Papa” wasn’t important to the emergence of the Bishop of Rome as the leader of the Church. It was a term of affection used by many Christians for their pastor and was used in a more formal sense in Alexandria decades before it was used of the Roman Bishop. It wasn’t until the 6th C that the word “Pope” was reserved exclusively for Rome’s Bishop, long after he’d already claimed primacy as Peter’s successor.

It’s important as well we make a distinction between the honor the Roman church held and the overarching authority its bishop later claimed. There’s ample evidence of the respect accorded Rome’s Christian community.

- Rome was, after all, the capital of the Empire.

- The church there was the largest and richest. By the mid-3rd C, it claimed some 30,000 members, served by 150 priests, supporting 1500 widows & the poor.

- It had a long record of remaining orthodox and generous.

For these reasons, it was regarded as the lead church of the Western Empire. Though there’s no solid historical evidence to support it, Christians of the 2nd thru 4th Cs believed Peter and Paul founded the church at Rome. It was thought each bishop of Rome handed his authority and office to his successor so that the current Pope, whoever that was, was sitting in the Apostolic seat of Peter.

We can see why this would be important to the Church when the Gnostics were a threat to the faith. They claimed to possess special secret knowledge & traditions that had been passed on by Jesus to the apostles, then to them. In contrast to this fiction, Rome could actually name their bishops all the way back to the original apostles. This list was memorized by young believers like state capitals are memorized by students today.

While the church at Rome was regarded with great respect by most believers, this honor didn’t always extend to its bishop. There’s much evidence of church fathers, like Irenaeus & Cyprian who disagreed vehemently with positions taken by the bishop of Rome. Until Constantine, there’s no evidence the church at large took direction from Rome’s lead pastor.

It’s important at this point to speak about the changes that took place in the structure of the churches during the 3rd & 4th Cs. This change came about for 2 reasons: Councils & Arch-bishops.

The first development that led to an alteration in the way churches developed was Church Councils. As the Church grew & individual congregations developed in more places, leaders of the Church recognized the need to coordinate their efforts & teaching. The emergence of heretics prompted elders and pastors to gather to discuss how to address the challenge of false teaching. These gatherings were at first informal and irregular, called at random by provincial leaders. In the 3rd C they began meeting annually in more formal Councils to share news and establish policy that would be observed in each church. These provincial councils proved so helpful, in the 4th C several provinces started sending their bishops to larger regional councils.

When Constantine became Emperor and the churches faced major obstacles, the call was sent out for all bishops to meet. The first such General or Ecumenical Council was held in 314 at Arles (are-L) although only the Western church leaders were called. The first true all-Church Council was held at Nicaea not far from Constantinople in 325 and dealt with the threat of Arianism. The findings of these General Councils became the rule for the churches.

The 2nd development that helped shape the Church was the emergence of archbishops. During the provincial and regional councils, all bishops were supposed to be equals. But in practice, some of the older bishops and those who lead larger, older, and more respected churches were held in higher regard. Also, as the Church grew it tended to locate first in urban centers, then reached out to the surrounding rural countryside where smaller churches sprang up, usually led by pastors sent out by the pastor of the nearest urban center. It was natural these rural pastors looked to their sending-church as their spiritual home and their sending-pastor as their spiritual leader. In other words, rural bishops looked to urban bishops as an arch-bishop. He might, in turn, look to some other bishop of an even larger city closer to Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, or Constantinople as his spiritual overseer. So, while all bishops were theoretically equal, practically they related to one another in a more hierarchal way, a hierarchy based on the size and prominence of the church and city where the bishop served.

You can see where this is going, can’t you? à Put church councils attended by archbishops together with a Church suddenly given access to Imperial favor and it’s a proverbial Pandora’s box of political scheming.

The move of the Empire’s political capital from Rome to Constantinople in 330 shifted the center of political gravity 900 miles East. Because location and proximity to political power had become increasingly important, suddenly, Constantinople was added to the list of Christian centers. And the bishop of Constantinople became another major player.

When Theodosius became Emperor in 379 and made Christianity the official state religion, Church politics moved to a whole new level. Hundreds of people feigned conversion and entered the church merely to gain political advantage. As we tracked in an earlier episode, in May 381, Emperor Theodosius convened a general Counsel in Constantinople but only called the Eastern bishops to attend. Bishop Damasus of Rome wasn’t invited. Theodosius wanted to close the book on Arianism so he convened the Council to endorse & ratify the Nicene Creed. The Eastern bishops decided to use the Council to raise their political coin by also ruling that the Bishop of Constantinople was second only to the Bishop of Rome in terms of authority. They based this on the premise Constantinople was the “New Rome.”

Damasus recognize this for what it was, a political power play. He and the other Western bishops responded in their own Council held a year later that Rome’s prominence wasn’t due to its proximity to the capital but its historic connection to Peter and Paul. It was from this Council at Rome in 382 that the Church first claimed the “primacy of the Roman church” based on Jesus’s supposed remark that He would build his church on Peter.

It was obvious by the end of the 4th C that East and West were headed in different directions.

The Eastern Church with its center at Constantinople became increasingly tied to Imperial power. In the West, things were dramatically different. Imperial power and presence were dissolving. The Church wasn’t only untying from political structures, as those structures themselves dissolved, the Church was increasingly looked to by the common people to provide governance.