by Lance Ralston | Mar 12, 2017 | English |

This is part 6 of our series titled The First Centuries, in Season 2 of CS. In the last episode we took a look at the Church Father Irenaeus. This episode we’ll consider Tertullian.

That may prompt some to wonder if we’re going to work our way through ALL the church fathers of the Early Church. Uh, no – we won’t. Just a few.

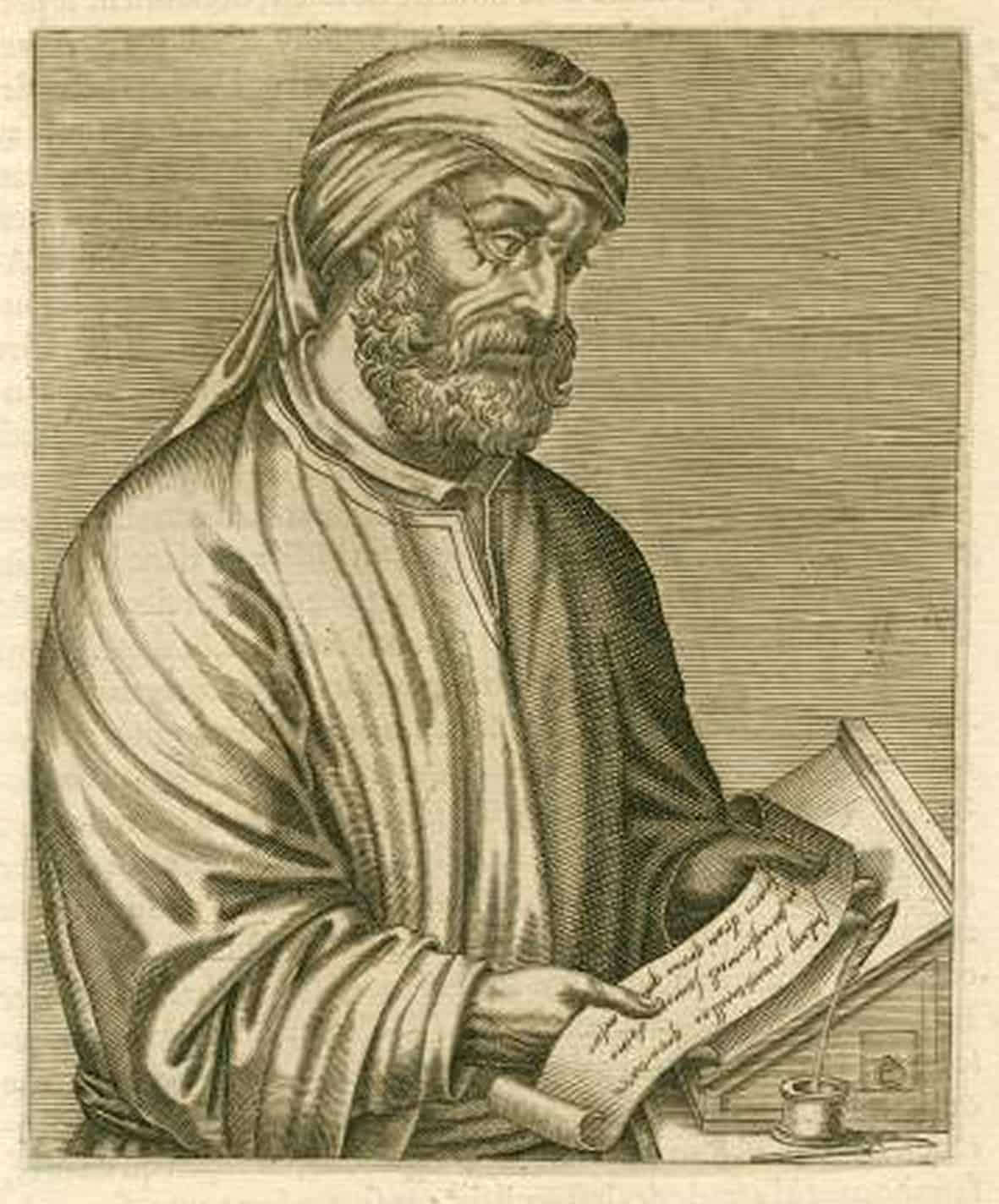

While he’s known to history as Tertullian, his full name was Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus.

(more…)

by Lance Ralston | Mar 5, 2017 | English |

The First Centuries – Part 5 // Irenæus

The historical record is pretty clear that the Apostle John spent his last years in Western Asia Minor, with the City of Ephesus acting as his headquarters. It seems that during his time there, he poured himself into a cadre of capable men who went on to provide outstanding leadership for the church in the midst of difficult trials. Men like Polycarp of Smyrna, Papias & Apolinarius of Hierapolis, & Melito of Sardis. These and others were mentioned by Polycrates, the bishop of Ephesus in a letter to Victor, a bishop at Rome in about AD 190.

These students of John are considered to be the last of what’s called The Apostolic Age. The greatest of them was Irenæus. Though he wasn’t a direct student of the Apostle, he was influenced by Polycarp, & is considered by many as one of the premier and first Church Fathers.

Not much is known of Irenæus’ origins. From what we can piece together from his writings, he was most likely born and raised in Smyrna around AD 120. He was instructed by Smyrna’s lead pastor, Polycarp, a student of John. He says he was also directly influenced by other pupils of the Apostles, though he doesn’t name them. Polycarp had the biggest impact on him, as evidenced by his comment, “What I heard from him, I didn’t write on parchment, but on my heart. By God’s grace, I bring it constantly to mind.” It’s possible Irenæus accompanied Polycarp when he traveled to Rome and engaged Bishop Anicetus in the Easter controversy we talked about last episode.

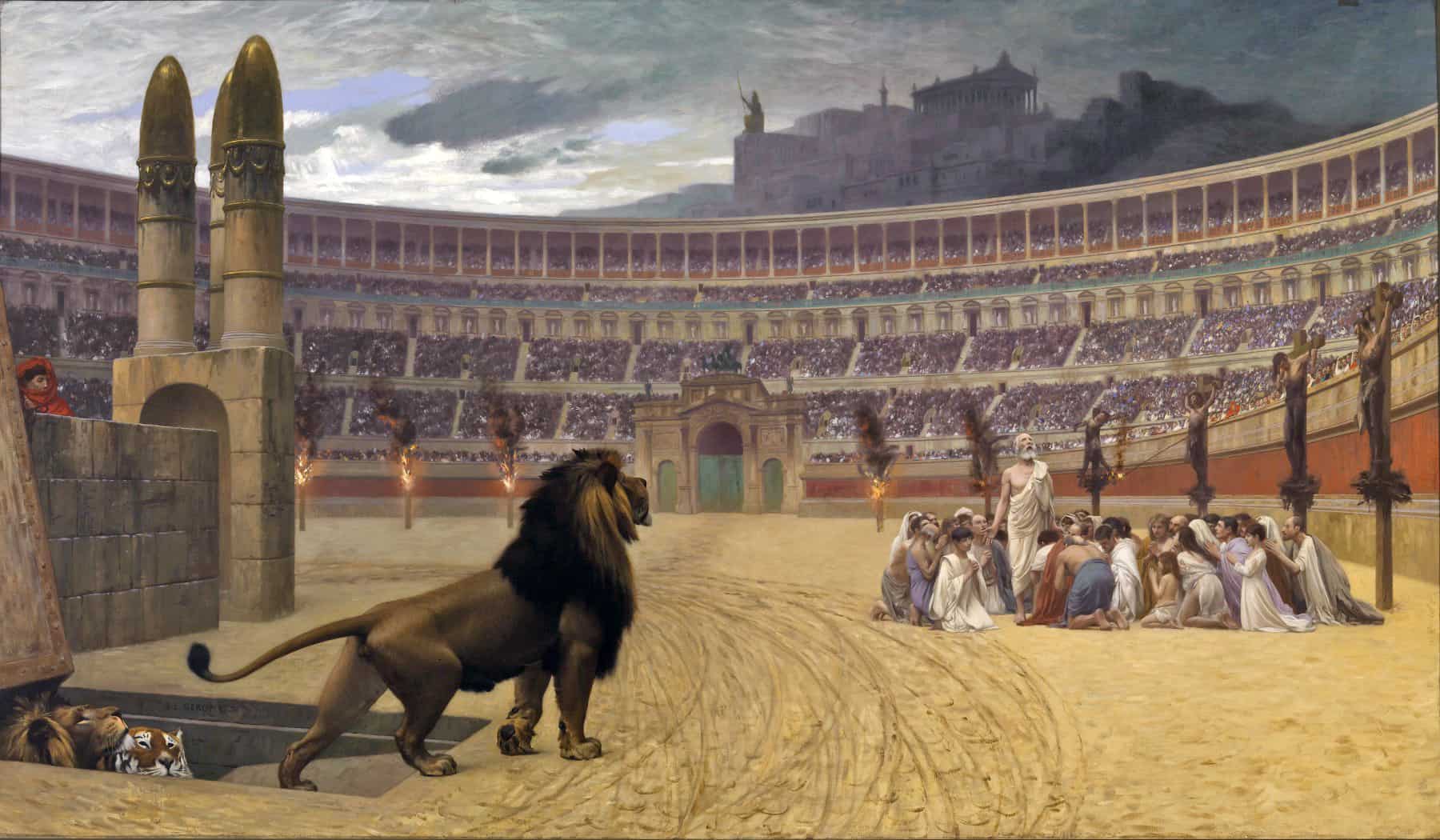

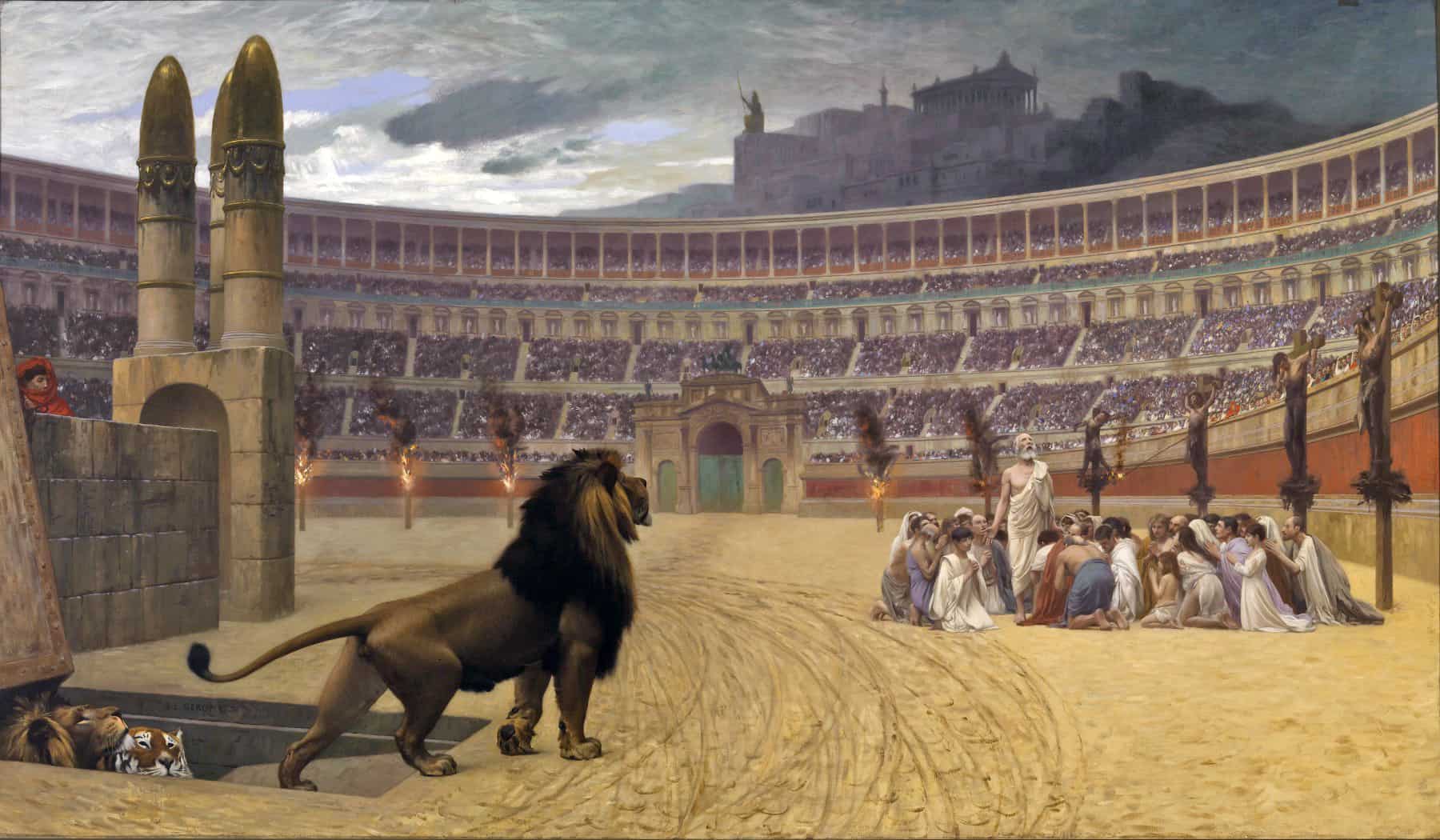

At some point while still a young man, Irenæus went to Southern Gaul as a missionary. He settled at Lugdunum where he became an elder in the church there. Lugdunum eventually became the town of Lyon, France. In 177, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the church in Lugdunum was hammered by fierce persecution. But Irenæus had been sent on a mission to Rome to deal with the Montanist controversy. While away, the church’s elderly pastor Pothinus, was martyred. By the time he returned in 178 the persecution had spent itself and he was appointed as the new pastor.

Irenæus worked tirelessly to mend the holes persecution had punched in the church in Southern Gaul. In both teaching and writing, he provided resources other church leaders could use in faithfully discharging their pastoral duties, as well as refuting the various and sundry errors challenging the new Faith. During his term as the pastor of the church at Lyon, he was able to see a majority of the population of the City converted to Christ. Dozens of missionaries were sent out to plant churches across Gaul.

Then, about 190, Irenæus simply disappears with no clear account of his death. A 5th C tradition says he died a martyr in 202 in the persecution under Septimus Severus. The problem with that is that several church fathers like Eusebius, Hippolytus, & Tertullian uncharacteristically fail to mention Irenæus’ martyrdom. Because martyrs achieved hero status, if Irenæus had been martyred, the Church would have marked it. SO most likely, he died of natural causes. However he died, he was buried under the altar St. John’s in Lyons.

Irenæus’ influence far surpassed the importance of his location. The bishopric of Lyon was not considered an important seat. But Irenæus’ impact on the Faith was outsized to his position. His keen intellect united a Greek education with astute philosophical analysis, and a sharp understanding of the Scriptures to produce a remarkable defense of The Gospel. That was badly needed at the time due to the inroads being forged by a new threat – Gnosticism, which we spent time describing in Season 1.

Irenæus’ articulation of the Faith brought about a unanimity that united the East & Western branches of the Church that had been diverging. They’d end up reverting to that divergence later, but Irenæus managed to bring about a temporary peace through his clear defense of the faith against the Gnostics.

Irenæus admits he had a difficult time mastering the Celtic dialect spoken by the people where he served but his capacity in Greek, in which he composed his writings, was both elegant & eloquent without running to the merely flowery. His content shows he was familiar with the classics by authors like Homer, Hesiod, & Sophocles as well as philosophers like Pythagoras & Plato.

He shows a like familiarity with earlier Christian writers such as Clement, Justin Martyr, & Tatian. But Irenæus is really only 1 generation away from Jesus and the original Apostles due to a couple long life-times; that of John, and then his pupil, Polycarp. We find their influence in Irenæus’ remark impugning the appeal of Gnosticism, “The true way to God, is through love. Better to know nothing but the crucified Christ, than fall into the impiety of overly curious inquires & silly nuances.” Reading Irenæus’ work on the core doctrines of the Faith reveal his wholehearted embrace of Pauline theology of the NT. Where Irenæus goes beyond John & Paul was in his handling of ecclesiology; that is, matters of the Church. Irenæus wrote on things like the proper handling of the sacraments, and how authority in the church ought to be passed on. A close reading of the 2nd C church fathers reveals that this issue was of major concern to them. It makes sense it would. Jesus had commissioned the Apostles to carry on His mission and to lay the foundation of the Faith & Church. The Apostles had done that, but in the 2nd C, the men the Apostles had raised up were themselves aging out. Church leaders were burdened with the question of how to properly pass on the Faith once for all delivered to the saints, to those who came next. What was the plan?

We’ll come back to that later . . .

Irenæus was a staunch advocate of what we’ll call Biblical theology, as opposed to a theology derived from philosophical musing, propped up by random Bible verses. He’s the first of the church fathers to make liberal use of BOTH the Old & New Testaments in his writings. He uses all four Gospels and nearly all the letters of the NT in the development of his theology.

His goal in it all was to establish unity among believers. He was so zealous for it because of the rising popularity of Gnosticism, a new religious fascination attractive an increasing number of Christians.

Historians have come to understand that like many emergent faiths, Gnosticism was itself fractured into different flavors. The brand Irenæus dealt with was the one most popular in his region; Valentinian Gnosticism, or, Valentinianism.

While several writings are attributed to Irenæus, by far his most important and famous was Against Heresies, his refutation of Gnosticism. Written sometime btwn 177 & 190, it’s 5 volumes is considered by most to be the premier theological work of the ante-Nicene era. It’s also the main source of knowledge for historians on Gnosticism and Christian doctrine in the Apostolic Age. It was composed in response to a request by a friend wanting a brief on how to deal with the errors of both Valentinus & Marcion. Both had taught in Rome 30 yrs earlier. Their ideas then spread to France.

The 1st of the 5 volumes is a dissection of what Valentinianism taught, and more generally how it differed from other sects of Gnosticism. It shows that Irenæus had a remarkable grasp of a belief system he utterly & categorically rejected.

The 2nd book reviewed the internal inconsistencies and contradictions of Gnosticism.

The last 3 volumes give a systematic refutation of Gnosticism from Scripture & tradition which Irenæus makes clear at that time were one and the same. He shows that the Gospel which was at first only oral, was subsequently committed to writing, then was faithfully taught in churches through a succession of pastors & elders. So, Irenæus says, The Apostolic Faith & tradition is embodied in Scripture, and in the right interpretation of those scriptures by pastors (AKA as bishops). And the Church ought to have confidence in those pastors’ interpretations of God’s Word because they’ve attained their office through a demonstrated succession. Of course, the succession Irenæus referred to was manifestly evident by virtue of the fact he wrote in the last quarter of the 2nd C & was himself, as we’ve seen, just a generation removed from the Apostle John.

Irenæus set all this over against the contradictory opinions of heretics who fundamentally deviated from this well-established Faith & simply could not be included in the catholic, that is universally agreed on, faith carved out by Scripture and its orthodox interpretation by a properly sanctioned teaching office.

The 5th and final volume of Against Heresies includes Irenæus’ exposition of pre-millennial eschatology; that is, the study of Last things, or in modern parlance – the End Times. No doubt he does so because it stood in stark contrast with the muddled teaching of the Gnostics on this subject. It might be noted that Irenæus’ pre-millennialism wasn’t unique. He stood squarely with the other writers of the Apostolic & post-apostolic age.

Irenæus’ view of the inspiration of Scripture is early anticipation of what came to be called Verbal plenary inspiration. That is, both the writings and authors of Scripture were inspired, so that what God wanted expressed was, without turning the writers into automatons. God expressed His will through the varying personalities of the original authors. He even accounts for the variations in Paul’s style across his epistles to his, at times, rapid-fire dictation & the agency of the Holy Spirit’s urging at different times and in different situations.

Irenæus’ emphasis on both Scripture and the apostolic tradition of its interpretation has been seen as a boon to the idea of establishing an official teaching magisterium in the Church. Added to that is his remarks that the church at Rome held a special place in providing leadership for the Church as a whole. He based this on Rome being the location of the martyrdom of both Peter & Paul. While Irenæus acknowledges they did not START the church there, he reasoned they most certainly were regarded as its leaders when they were there. And there was a tradition that Peter appointed the next bishop, one Linus, to lead the Church when he was executed. While it’s true Irenæus did indeed suggest Rome ought to take the lead, he said it was the CHURCH there that ought to do so; not its bishop. The point may seem minor, but it’s important to note that Irenaeus himself resisted positions taken by the Bishop at Rome. In our last episode, we noted his chronicle of Polycarp’s & Anicetus’ disagreement over when to celebrated Easter. Anicetus’ successor was Bishop Victor, who took a hardline approach with the Quartodecamins and wanted to forcefully punish them. While as the bishop of the church in Lyon, Irenaeus was ready to follow the policy of the Church at Rome, he objected to Victor’s heavy-handedness and reminded him of his predecessor’s more fair-minded policy.

So while Irenaeus does indeed urge a role of first-place for the Church at Rome, we can’t go so far as to say he establishes the principle of the primacy of the bishop of Rome. He’s not an apologist for papal primacy.

Nor does he advocate apostolic succession as it’s come to be defined today. What Irenaeus does say is that the Scriptures have to be interpreted rightly; meaning, they have to align with that which the Apostles consistently taught, and that the people who were to be trusted to that end were those linked back to the Apostles because they’d HEARD them explain themselves.

He argued this because the Gnostics claimed a secret oral tradition given them from Jesus himself. Irenaeus maintained that the pastors & elders of the Church were well-known and linked to the Apostles and had always maintained the same message that wasn’t secret at all. Therefore, it was those pastors who provided the only safe interpretation of Scripture.

For Irenaeus, apostolic authority was only valid so long as it actually squared with apostolic teaching, which itself was codified in the Gospels and epistles of the NT – along with what the direct students of the Apostles said they’d taught. Irenæus didn’t concoct a formula for the passing of apostolic authority from one generation to the next in perpetuity.

Irenaeus became a treasured authority for men like Hippolytus and Tertullian who drew freely from him. He also became a major source for establishing the canon of the NT. He regarded the entire OT as God’s Word as well as most of the books our NT while excluding a large number of Gnostic pretenders. There’s some evidence that before Irenaeus, believers lined up under different Gospels as their preferred accounts of the Life of Jesus. The Churches of Asia Minor preferred the Gospel of John while Matthew was the most popular overall. Irenaeus made a convincing case that all 4 Gospels were God’s Word. That made him the earliest witness to the canonicity of M,M,L & J. This stood over against the accepted writings of a heretic named Marcion who only accepted portions of Luke’s Gospel.

Irenaeus cited passages of the NT about a thousand times, from 21 of the 27 books, including Revelation. Inferences to the other books can be found as well.

Irenaeus provides a perfect bridge from the Apostles to the next phase of Church History presided over by the Fathers, of which he’s considered among the first.

by Lance Ralston | Feb 26, 2017 | English |

Have you noticed that, generally-speaking, Christians like to argue?

Maybe we get it from our spiritual ancestors, the Jews. Once while on a tour of Jerusalem at what are called the Southern Steps of the Temple Mount, our Jewish guide told us that a frequent joke among his people was that where there are 2 Jews, there’s 3 opinions.

Yeah; it seems controversy has been a part of the history of The Church since its inception. And maybe that’s really more a “human” tendency than something unique to, or the sole prerogative of the followers of Jesus.

(more…)

by Lance Ralston | Feb 12, 2017 | English |

In part 1 we took a look at some of the sociological reason for persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. Then last time we began a narrative-chronology of the waves of persecution and ended with Antonius Pious.

A new approach in dealing with Christians was adopted by Marcus Aurelius who reigned form 161–180. Aurelius is known as a philosopher emperor. He authored a volume on Stoic philosophy titled Meditations. It was really more a series of notes to himself, but it became something of a classic of ancient literature. Aurelius bore not a shred of sympathy for the idea of life after death & detested as intellectually inferior anyone who carried a hope in immortality.

(more…)

by Lance Ralston | Feb 5, 2017 | English |

This is part 2 in our follow-up series on the first centuries in Church History. We’re concentrating on the persecution Jesus’ followers endured. In part 1, we examined the social & civic reasons for persecution in the Roman Empire.

The suspicion of nefarious intent by Christians, fueled by their withdrawal from society due to its tacit connection to paganism, morphed into a suspicion of covert actions Jesus’ followers were taking to subvert society. Why were Christians so secretive if they weren’t in fact doing something wrong? And if the rumors were true, Christians WERE doing odd things; like pretending slaves had the same dignity as freemen; that women and children were to be honored as equal to men; and they rescued exposed infants. Why, if they kept all that up, and more joined their cause, what was to become of the world? It would look very different from the one that had been.

(more…)

by Lance Ralston | Jan 29, 2017 | English |

Welcome BACK to Communion Sanctorum: History of the Christian Church.

We ended our summary & overview narrative of Church History after 150 episodes; took a few months break, and are back to it again with more episodes which aim to fill in the massive gaps we left before.

This time, we’ll do series that go into detail on specific moments, movements, people, places, and other topics.

(more…)

by Lance Ralston | Sep 4, 2016 | English |

The final episode of Communio Sanctorum. We look briefly at the reaction of some Protestants to Manifest Destiny. DL Moody, The Holiness Movement, Phoebe Palmer, The Azusa Street Revival.

This 150th episode of CS is titled The End.

150 episodes! And this is the rebooted v2. We had a hundred episodes in v1 before I started over again in an attempt to clean up the timeline and fill in some gaps.

(more…)

by Lance Ralston | Aug 28, 2016 | English |

This 139th episode is titled Evangementalism,

We’ve spent a couple of episodes laying out the genesis of Theological Liberalism, and concluded the last episode with a brief look at the conservative reaction to it in what’s been called Evangelicalism. Evangelicalism was one of the most important movements of the 20th C. The label comes from that which lies at the center of the movement, devotion to an orthodox and traditional understanding of the Evangel, that is, the Christian Gospel – the Good News of salvation through faith in Jesus Christ.

While Evangelicalism is used today mainly to describe the theological movement that came about as a reaction to Protestant theological liberalism, the term can be applied all the way back to the 1st C believers who referred to themselves as “People of the Gospel,” the Evangel. The term was resurrected by Reformers to call themselves “evangelicals” before identifying as Protestants or any of the other labels used for protestant denominations today.

The modern flavor of Evangelicalism came about as a merging of European Pietism and revivals among Methodists in England. We might even locate the origin of modern Evangelicalism in the First Great Awakening of the mid-18th C. Its midwives were people like Whitefield, Tennent, Freylinghuysen, and of course Jonathan Edwards.

Since major stress of all these was the need for a conversion experience and spiritual new birth, revivalism and an emphasis on the task of evangelism have been front and center in Evangelicalism.

As we’ve seen in a past episode, the First Great Awakening was followed a century later by the Second which began in the United States and spread to Europe, then the rest of the world and had a huge impact on how Christians viewed their Faith. What’s remarkable about the Second Great Awakening, is that it came at a time when many church leaders lamented the low state of the Church in Western Civilization. Christianity’s enemies gleefully wrote its obituary. Theological Liberalism helped to push the Faith toward an early grave. But the Second Great Awakening literally shook North American and Europe to their core. A wave of missionaries went out across the globe as a result, spreading the Faith to places no church had existed for hundreds of years, and in some cases, ever before.

In newly settled regions on the American frontier, Evangelicalism was carried out in week-long “camp meetings.” Think of a modern concert with multiple bands. Camp meetings were like that, except in place of bands playing music were preachers passionately preaching the Gospel. Might not sound too appealing to our modern sensibilities, but the lonely pioneers of the frontier turned out in large crowds. They’d been too busy building homesteads to consider constructing frontier churches. But now they returned home to do that very thing.

One of the largest of these camp meetings took place at Cane Ridge in Kentucky in August 1801. Upwards of 20,000 gathered to listen to Protestant preachers of all stripes.

Methodist minister Francis Asbury was just one of several circuit-riders who carried the Gospel all over the frontier. Both Baptists and Methodists worked tirelessly to bring the Gospel to blacks. But the fierce racism of the time refused to integrate congregations. Separate churches were plated for black congregations, of which there were many. In the early 19th C, Richard Allen left the Methodist Church to found the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In the US, it wasn’t long before Evangelical Baptists and Methodists outnumbered older denominations of Episcopalians and Presbyterians, groups where theological liberalism had infiltrated.

Charles Finney was an attorney-turned-revivalist who transferred the excitement and energy of the rural camp-meetings to the urban centers of the American Northeast. An innovator, Finney encouraged the newly converted to share the story of how they came to the Faith – called ‘giving your testimony.’ He set what he called an “anxious bench” near the front of rooms where he spoke as a place where those who wanted prayer or to make a profession of faith in Christ could sit. That eventually turned into the modern ‘altar call’ that’s a standard fixture of many Evangelical churches today.

By the start of the American Civil War in the mid-19th C, Evangelicalism was the predominant religious position of the American people. In an address delivered 1873, Rev. Theodore Woolsey, one-time president of Yale could say, without the least bit of controversy; “The vast majority of people believe in Christ and the Gospel. Christian influences are universal. Our civilization and intellectual culture are built on that foundation.”

While there are many brands, flavors, and emphases inside modern Evangelicalism, it’s safe to characterize an Evangelical as someone who holds to several core beliefs: those being à

1) The authority and sufficiency of Scripture

2) The uniqueness of salvation through the cross of Jesus Christ,

3) The need for personal conversion

4) And the urgency of evangelism

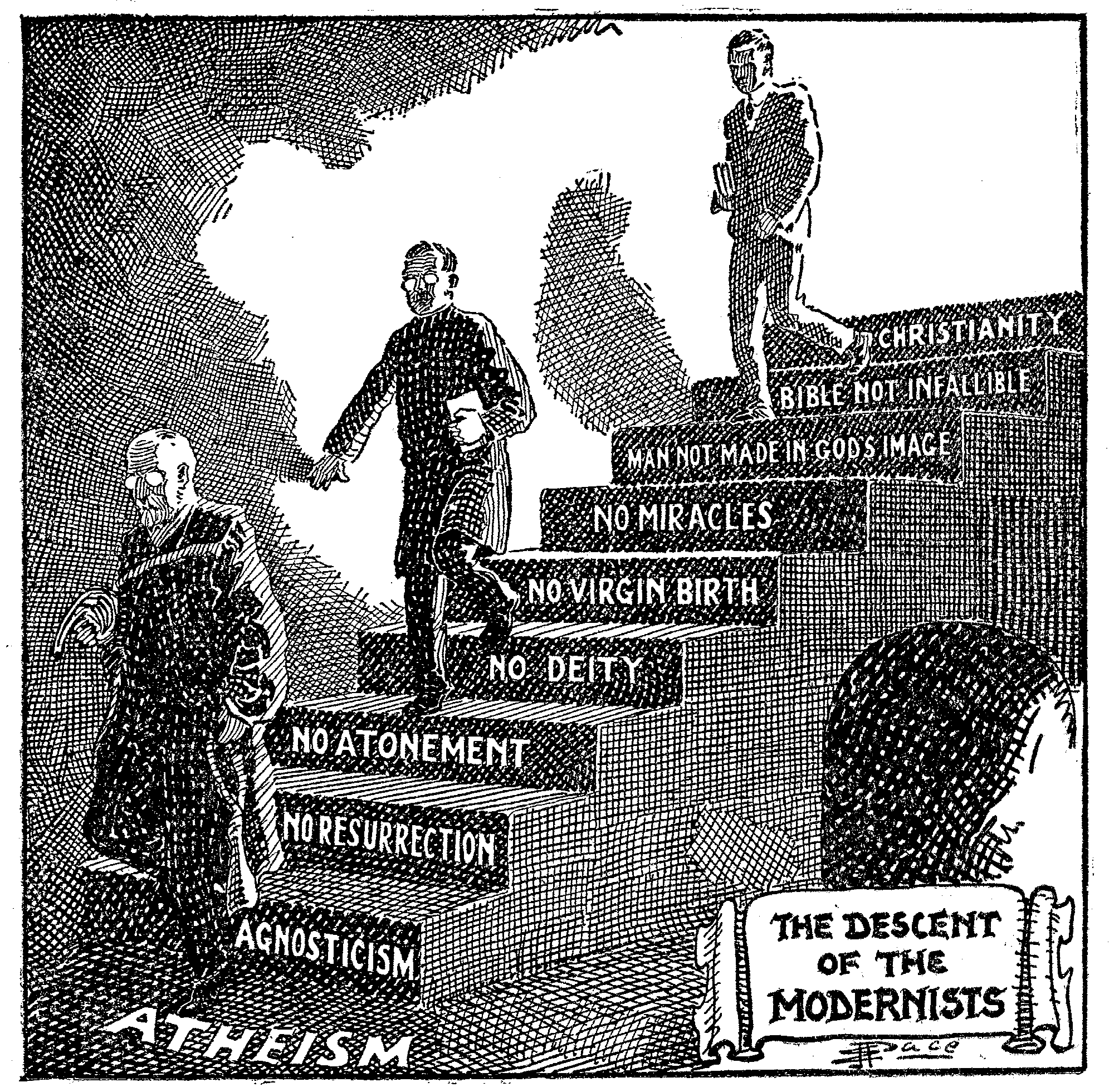

Further refining of Evangelicalism took place when there was a debate over the first of its core doctrines – the authority and sufficiency of Scripture. This is where Fundamentalism diverged from Evangelicalism. The other three core distinctives of Evangelicalism all rest on the authority and sufficiently of the Bible. And while Evangelicalism began as a reaction to theological liberalism, some of the ideas of that liberalism crept into some Evangelical’s view of Scripture.

You see, it’s one thing to say Scripture is authoritative and sufficient and another to then say the entire Bible is Scripture. Is the Bible God’s Word, or does it just contain God’s Word? Do we need scholars and those properly educated to tell us what is in fact Scripture and what’s filler? Are the actual WORDS God’s Words, or do the words need to be taken together collectively so that it’s not the words but the meaning they convey that makes for God’s authoritative message?

Some Evangelical leaders noticed their peers were moving to a position that said the Bible wasn’t so much God’s Word as it contained God’s Message. While they weren’t as extreme as the Liberal Theologians, they effectively ended up in the same place. This debate goes on in the Evangelical church today and continues to be the source of much unrest.

Conservative Evangelicals started linking the authority of Scripture to the doctrine of inerrancy; that is, belief the Bible’s original writings contained no errors, and that because of the laborious process of transmission of the texts over time, while we can’t say our modern translations are perfect or without any error, they are virtually inerrant; they are trustworthy versions of the originals.

At the dawn of the 20th C, Princeton Theological Seminary became the epicenter of this debate as a leading defender of the authority of the Bible. It had long been an advocate for the infallibility of Scripture under such luminaries as Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, his son, AA Hodge, and BB Warfield. In a seminal essay on the doctrine of Inspiration in the Princeton Review, AA Hodge and BB Warfield defined inspiration as producing the “absolute infallibility” of Scripture. They said the autographs, the original writings of the Bible were free from error, not just in regard to theological matters, but in contradiction to what theological liberalism claimed, they were without error in regard to ALL their assertions, including those touching science and history.

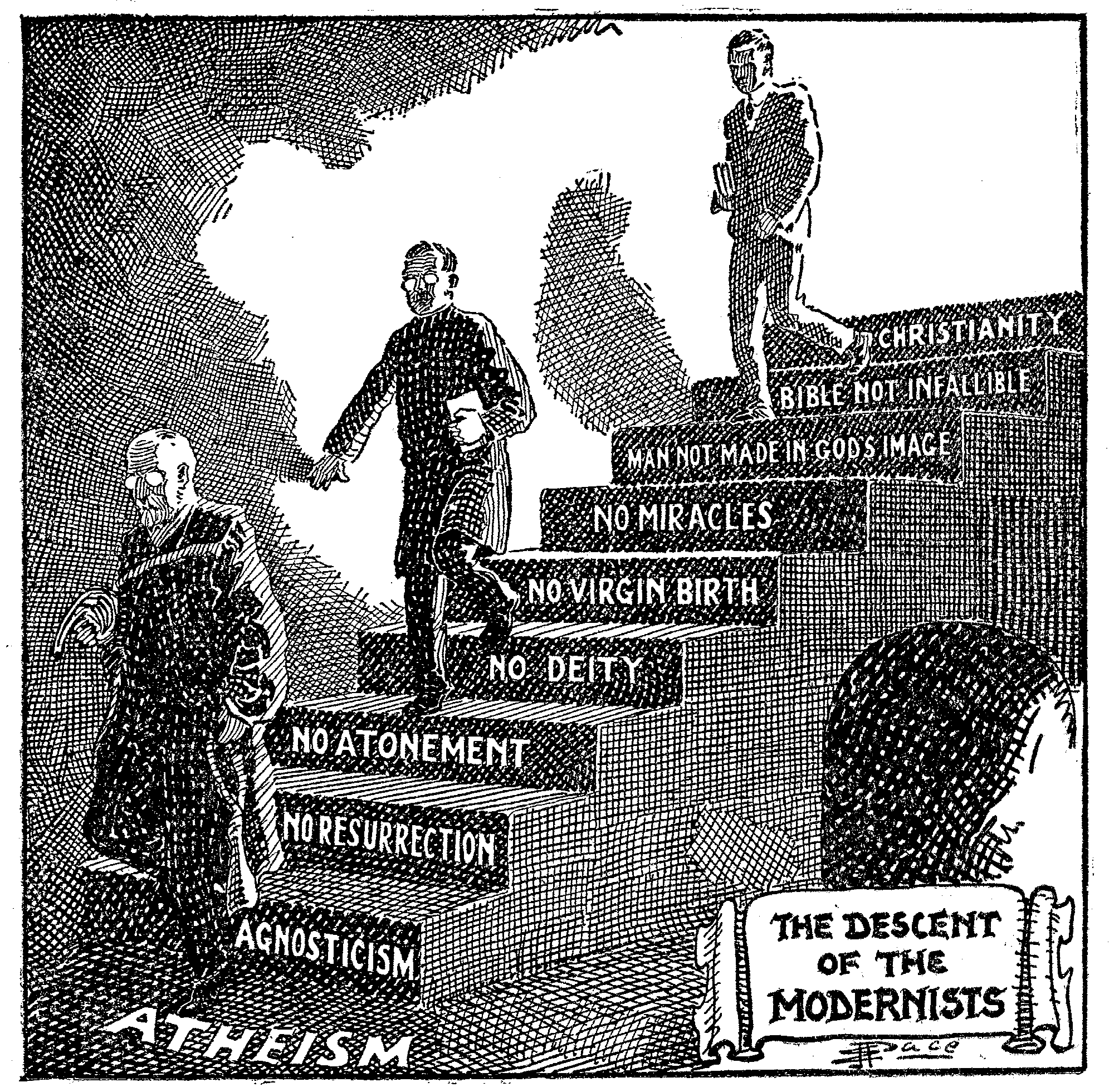

The theological liberalism coming from Europe had a mixed reception in the US at the outset of the 20th C. At first, most churches remained conservative and blissfully unaware of the slow sea-change taking place in the intellectual centers of American universities and seminaries. Battle lines were drawn between liberals and conservatives who were branded with a new label = Fundamentalists. The battle they carried out in the hallowed halls of academia soon spilled over into the pews. It was referred to as the contest between modernists and fundamentalists.

While modernists embraced a host of varying ideologies, they shared two presuppositions.

First, they urged, Christianity must be reframed in light of new insights; meaning the tenants of Protestant Liberalism.

Second, the Faith had to be liberated from the cultural encrustations of traditionalism that had obscured the REAL MEANING of the Bible. What that effectively meant was that ALL and ANY traditional beliefs about what the Bible said was no longer valid. It was a knee-jerk rejection of conservatism.

Though the term Fundamentalism wasn’t coined until 1920, it flowed from the 1910 publication The Fundamentals. It was a synthesis of different conservative Protestants who united to battle the Modernists who seemed to be taking over Evangelicalism. Fundamentalists banded together to launch a counteroffensive.

There were 2 streams of the early Fundamentalist movement.

One was intellectual fundamentalism led by J. Gresham Machen [Gres’am May-chen] and his Calvinist peers at Princeton. [the ‘h’ in Gresham is silent!]

The other was populist fundamentalism led by CI Schofield who produced the best-selling Scofield Reference Bible which contained his expansive notes and laid out a dispensationalism many found appealing.

Other notable fundamentalist leaders were RA Torrey, DL Moody, Billy Sunday, and the Holiness Movement that moved in several denominations, most notably the Nazarenes.

While the intellectual and populist streams of fundamentalism attempted to unite in their opposition to modernism, there were simply too many doctrinal differences between all the various groups inside the movement to allow for a concerted strategy in dealing with Liberalism. As a result, Modernists were able to continue their infiltration and take-over of the intellectual centers of the Faith.

In reaction to modernists, in 1910, a group of conservative Presbyterians responded with five convictions that came to be considered the core Fundamentals from which the movement derived its name. Those five convictions flowed from their certainty in the inerrancy and infallibility of Scripture. They were . . .

1) The inerrancy of the original writings.

2) The virgin birth of Jesus.

3) The substitutionary atonement of Jesus on the cross.

4) His literal, bodily resurrection.

5) A belief that Jesus’ miracles were to be understood as real events and not merely literary mythology meant to teach some ethical imperative. Jesus really fed thousands with a few fish and loaves, really raised Jairus’ daughter from the dead, and really walked on water.

These fundamentals were elaborated and released between 1910 and 15 in a set of booklets called The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth. The Stewart brothers funded their publication and ensured they were distributed to every Christian leader across the US. Some three million copies were circulated before WWI to combat the threat of Modernism.

by Lance Ralston | Aug 21, 2016 | English |

The title of this 138th episode is Liberal v Evangelical

In our last episode, we considered the philosophical roots of Theological Liberalism. In this, we name names as we look at its early leaders and innovators.

When I took a philosophy course in college, the professor dispensed on us sorry, unwashed noobs his understanding of faith and reason. After a lengthy description of both, he concluded by saying that faith and reason had absolutely nothing to do with each other. Reason dealt with the evidential, that which was perceived by the senses, and what logic concluded were rationally consistent conclusions drawn from that evidence. Faith, he declaimed, was a belief in spite of the evidence. When I asked if he was thus saying faith was irrational, he just smiled.

That professor was an adherent of Immanuel Kant’s philosophy. In Kant’s work Critique of Pure Reason, published in 1781, Kant argued reason is able to comprehend anything in the realm of space and time; what he called the phenomenal realm. But reason is useless in accessing the noumenal, or spiritual realm transcending time and space.

Kant didn’t argue against the existence of the spiritual realm. He simply said it’s only something we can experience by feelings. We can’t really THINK about it in the sense that it touches the rational mind.

Traditional, orthodox Christians pushed back against the Kantian view of faith as feeling by reminding themselves Jesus said the greatest command was to love God with all they had, including their minds. But liberals found in Kant’s philosophy a justification for unhitching reason from faith and for allowing modern people to live in a secular world while still enjoying the benefits of religious sentiments about ultimate meaning. In other words, it allowed them to get along content with the WHAT of life in the world, without having to bother much with the HOW, or concern themselves at all with WHY.

A few years after the publication of Kant’s Critique, the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, going against the heart and soul of Christian apologetics dating back hundreds of years, said the heart of Christian Faith isn’t a historical event, like the Resurrection. It was, he argued, a feeling of one’s absolute dependence on a reality beyond one’s self. That awareness, he claimed, could be developed to the point where a person would be able to imitate Jesus’ own good deeds.

He wrote, “The true nature of religion is immediate consciousness of Deity as found in ourselves and the world.” This earned Schleiermacher the title, Father of Theological Liberalism.

Schleiermacher was born in a pious Moravian home, but as a young man, he imbibed the rationalism of the Enlightenment and became an ardent apologist for accommodating Christianity to popular society. As a professor of the newly founded University of Berlin, he insisted debates over proofs of God’s existence, the authority of Scripture, and the possibility of miracles weren’t the issues they ought to focus on. He said that the heart of religion had always been feeling, rather than rational proofs. God is not a theory used to explain the universe. Rather, God is to be experienced as a living reality. For Schleiermacher, religion isn’t a creed to be pondered by the rational mind. It’s based on intuition and a feeling of dependence.

Orthodox Christians who identified religion with creedal doctrines, Schleiermacher maintained, would lose the battle for the Faith in the Modern world because those creeds were no longer rationally acceptable. Religion needed to find a new base. He located it in feelings.

Sin, Schleiermacher said, was the result of people living by themselves, isolated from others. To overcome the sin that makes man independent from God and others, God sent a mediator in Jesus Christ. Christ’s uniqueness wasn’t in doctrines about his virgin birth or deity. No à What made Jesus a Mediator who can help us is the perfect example he was of one utterly dependent on God. By meditating on Christ’s example, and feeling our own inner sense of dependence on the universe around us, we too can experience God as Jesus did.

In Schleiermacher’s theology, the center of religion shifts from Scripture to experience. So, the Biblical criticism we looked at in the last episode can’t harm Christianity, since the real message of the Bible speaks to an individual’s own subjective pursuit of the divine. The Bible doesn’t need to be factual or true, as long as it affects the feeling of dependence that is the spark that leads to spiritual illumination.

Albrecht Ritschl enlarged on Schleiermacher’s ideas, taking them mainstream.

For Ritschl, religion had to be practical. It began with the question, “What must I do to be saved?” But he eschewed the merely theoretical. So the question “What must I do to be saved?” can’t just mean, “How do I get to heaven after I die?” Ritschl said salvation meant living a new life, free from sin, selfishness, fear, and guilt.

Ritschl’s practical Christianity had to be built on fact, so he welcomed the search for the historical Jesus we talked about in the last episode. The great fact of the Christian Faith is the impact Jesus made on history. Nature, he maintained, gives an ambiguous understanding of God while History presents us with moments and movements that convey meaning.

History conveys meaning alright – but I’m not sure all that history’s given us a less ambiguous understanding of God than Nature.

Ritschl asserted religion rests on human values, not science. Science conveys facts, things as they are. Religion weighs those facts and attributes more or less value to them.

Many Christians of the late 19th C considered Ritschl’s work helpful. It freed them from the destructive impact of the increasingly secular pursuits of history and science. It allowed biblical criticism to use scientific methodology in determining things like authorship, date, and the meaning of Scripture. But it recognized religion is more than facts. Values aren’t under the purview of science; that’s religion’s turf.

Protestant Theological Liberalism accepted higher criticism’s denial of Jesus’ miracles, His Virgin Birth, and His preexistence. But that did not in any way diminish Jesus’ importance. For Liberals, His deity didn’t need to arise from His essence. It resides in what Jesus MEANS. He’s the consummate human being who shows us the path to enlightenment and nobility. He’s the embodiment of supremely high ethical ideals whose example inspires us to emulate His example. For Liberal Christians, The Church didn’t come out of some actual, factual events around Jerusalem 2000 years ago, it arose from Jesus’ awe-inspiring example. The Church isn’t a community of people who believe in a literally resurrected Savior so much as a value-creating community that gives meaning and mission to life. That mission is to create a society inspired by love, the Kingdom of God on earth.

The impact of this Theological Liberalism wasn’t felt in just one denomination or region. It challenged traditional groups all over Europe and North America. It appeared in the churches of New England with the moniker: New Theology. Its leading advocates came out of traditional Calvinism. Its greatest early popularizer was Lyman Abbott. Then came Henry Ward Beecher, William Tucker, and Lewis Stearns.

Prior to 1880, most New England ministers and churches held to basic orthodox doctrines . . . The sovereignty of God; the depravity of humanity in original sin; the atonement of Christ; the necessity of the Holy Spirit in conversion; and the eternal separation of the saved and lost in heaven and hell.

But after 1880, each of those beliefs came under withering fire from Liberals. The most publicized controversy took place at Andover Seminary. The seminary was established by Congregationalists 80 years before to counter Unitarian tendencies at Harvard. Attempting to preserve Andover’s orthodoxy, the founders required the faculty to subscribe to a creed summarizing their adherence to classic Calvinism. But by 1880, under the influence of liberalism, several of the faculty could no longer make the pledge. The spark that lit the flames of controversy was a series of articles in the Andover Review by liberal professors who argued the unsaved who die without any knowledge of the Gospel will have an opportunity at some future point to either accept or to reject the Gospel before facing judgment.

Andover’s board filed an action against one of the authors of the articles as a test case. After years of moves and counter-moves, in 1892 the Supreme Court of Massachusetts voided the action of the Board. By then, most denominations had their own tussles with liberalism seeking to infiltrate their colleges and schools.

The response to Protestant theological liberalism was a movement which many of our listeners have heard of – Evangelicalism.

Evangelicalism began in England in the 19th C, an epoch that in some ways singularly belonged to Great Britain. It was the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. London became the largest city and financial center of the World. British trade circled the globe; her navy ruled the seas. By 1914, Britannia ruled the most expansive empire in history.

But the rapid commercial and industrial growth wasn’t equally distributed across England’s population. The pace of change left many stunned. Every traditionally sacred institution cracked at its foundation. Some feared the horrors of the French Revolution were about to be repeated on England’s hallowed shores while others sang the praises of Lady Progress and dreamed of even greater advances. They regarded England as the vanguard of a new day of prosperity and liberty for all. Fear and hope mingled.

As the Age of Progress dawned in England, Protestants attended either the Anglican Church or one of the Nonconforming denominations of Methodist, Baptists, Congregationalist, and a handful of smaller groups. But now, for maybe the first time, Christians from different denominations also formed specialized groups with a specific aim; like distributing Bibles, redressing poverty in urban slums, teaching literacy, and supporting missionaries in the far-flung reaches of the Empire.

While liberalism grew in seminaries and colleges among professors and theologians, many ministers working in churches as local pastors and the people in the pews grew increasingly uncomfortable with the emerging doubt in the intellectual centers of their denominations. They may not be as sophisticated or learned in the academic pursuits of the experts, but by golly, they didn’t think a PhD was necessary to believe in or follow God. And if holding a Ph.D. meant having to deny cardinal doctrines of the Faith, then no thank YOU, very much.

Evangelicals pushed back on Liberals, saying Christians ought not just to accept what Science says, just because it says it. History proves today’s so-called “science” is tomorrow’s mockery. The Christian faith isn’t just about how it makes you feel and the meaning it brings you. It’s a Faith that rests on the actual, literal events of history. To deny those facts and events is to depart from traditional, orthodox Christianity.

The Evangelical Movement began with the work of John Wesley and George Whitefield. Its main characteristics were its emphasis on personal holiness, arising from a conversion experience. It was also devoted to a practical concern for serving a needy world. That holiness and service were nourished by devotion to the Bible which was regarded as inspired and inerrant. The Evangelical message went forth from a large minority of Anglican pulpits and a majority in other denominations.

The headquarters of Evangelicalism was a small village three miles from London called Clapham. It was the residence of a group of wealthy Evangelicals who practiced remarkable personal piety. The group’s spiritual leader was John Venn, a man of culture and sanctified common sense. They met for Bible study, conversation, and prayer in the library of the well-to-do banker, Henry Thornton.

But the most famous member of the Clapham Groups was William Wilberforce, the parliamentary statesman. Wilberforce found a universe of talented help for Evangelical causes among his Clapham friends. These included John Shore, Governor-General of India; Charles Grant, Chairman of the East India Company; James Stephens, Under-Secretary for the Colonies; and Zachary Macauley, editor of the Christian Observer.

At the age of just 25, Wilberforce was dramatically converted to Christ after reading Doddridge’s Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul. He possessed all the qualities for outstanding leadership: ample wealth, a liberal education, and outstanding talent. Prime Minister William Pitt said Wilberforce had the greatest natural eloquence he’d ever known. Several testified of his amazing capacity for close friendship and his superior moral principles. For many reasons, Wilberforce seemed providentially prepared for the task and the time.

He once said, “My walk is a public one: my business is in the world, and I must mix in the assemblies of men or quit the part which Providence has assigned me.”

Under Wilberforce’s leadership, the Clapham friends were knit solidly together. At the Clapham mansion, they held what they called “Cabinet Councils.” They discussed the wrongs and injustices of their country, and the battles they’d have to fight. Inside and outside Parliament, they moved as one, delegating to each member the work he could do best to accomplish their common purpose.

They founded . . .

- The Church Missionary Society

- The British and Foreign Bible Society

- The Society for Bettering the Condition of the Poor

- The Society for the Reformation of Prison Discipline

- and many more.

Their greatest effort though was the campaign to end slavery. Which is a tale I’ll leave for others to follow up.

While the Clapham group accomplished much, it was their role in abolishing slavery that provides a sterling example of how an entire society can be influenced by just a few.

by Lance Ralston | Aug 14, 2016 | English |

The episode is titled Why So Critical?

Two episodes back we introduced the themes that would lead eventually to Theological Liberalism. The last episode we talked a bit about how the church, mostly the Roman Catholic church, pushed back against those themes. In this episode, we’ll go further into the birth of liberalism.

The 20th century was unkind to Theological Liberalism, with its shining vision of the Universal Brotherhood of Man under the Universal Fatherhood of God. Yet, many mainline Protestant denominations still hold solidarity with Liberalism. It was Professor Sydney Ahlstrom’s view that liberals had provoked as much controversy in the 19th century as the Reformers did in the 16th. The reason for that controversy lay in their objective, stated by one of its premier advocates and popularizers – Harry Emerson Fosdick. In his autobiography, The Living of These Days, the influential pastor of the famous Riverside Church in New York City, said the aim of liberal theology was to make it possible “to be both an intelligent modern and a serious Christian.”

Liberals hoped to address a problem may be as old as The Faith itself: That is, how can Christians reconcile their faith to the intellectual climate of their time without compromising the Essentials of The Gospel? By the evaluation of modern Evangelicals, Liberalism failed in that quest precisely because they DID compromise those essentials in their desire to be relevant among their unbelieving peers. Richard Niebuhr expressed the irony of theological liberalism when he said in liberalism “a God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a Cross.”

Personally, I’ve been reluctant to produce this episode because the more I’ve studied Theological liberalism, the less certain of being able to handle it competently I’ve grown. Definitions for it are no easier than for political liberalism. In fact, many deny that Protestant liberalism is a theology at all. They refer to it as an “outlook,” or “approach.” Henry Coffin of Union Seminary described liberalism as a “spirit” that honors truth so supremely and it craves the freedom to discuss, publish, and pursue what it believes to be true.

But then, if THAT is true, it must certainly lead to certain convictions that derive values and produce judgments. And THAT is precisely what we see the history of Protestant liberalism producing.

In the words of Bruce Shelley, “Liberals believed Christian theology had to come to terms with modern science if it ever hoped to claim and hold the allegiance of intelligent men.” So liberals refused to accept religious beliefs on authority alone. They insisted faith must submit to reason and experience. Following the thinking of the Enlightenment, of which they were the spiritual children, they claimed the human mind was capable of thinking God’s thoughts after Him. So, the best insight into the nature and character of God wasn’t His self-revelation in Scripture, which smacked of the old authoritarianism they eschewed; it was human intuition and reason.

By surrendering to what we’ll call “the modern mind” liberals accepted the assumption of their time that the universe was a massive but synchronized machine, like a well-made watch. The key to this machine was Unity.

I’ll come back to that in a moment, but a little editorializing seems in order. And while some may be rolling their eyes, I think this is germane to what this podcast is – a review of History – specifically Church History. I just made reference to “the modern mind.”

Modern is another term that has multiple meanings. Historians use it to refer to the Modern Era, which they debate over the time span of, but let’s go with the common view that it runs from about 1500 to 1900-ish. So wait! IF the Modern Era ended at the beginning of the 20th century, what Era are we in now? The Atomic or Nuclear Era, the Post-Modern Era, the Information Age? Different labels get assigned to the current historical epoch. But don’t we still refer to current trends and fashions as being “modern”? Aren’t we “moderns” in the sense that we’re living NOW? Not many people would want to be considered not modern.

It gets confusing because the word modern is plastic with a lot of different meanings and connotations. But here’s where it adds to the confusion as it relates to our discussion on theological liberalism, and some of this spills over into political liberalism. There was a desire to accommodate Christian theology to the modern mind. By which emerging liberals meant accepting the findings of “modern science” as (air-quote) fact and making theology fit into those supposed facts. But there’s a difference, a vast difference between facts and interpretations of facts. A few years after a so-called “Fact” was established by science, others came along to say, “Yeah, uh, we weren’t quite right about that. It’s actually this.” And, it wasn’t uncommon for even that revised new paradigm to be revised yet again.

Is coffee good or bad for you? Right now, it’s good. But wait a month and it’ll be bad again, But not to worry, a year out, coffee will be the key to long life and amazing prosperity. Okay. I exaggerate, but not by much.

My point is this, the current moment, what we mean by at least ONE of those definitions of “modern” – has a nasty habit of thinking that just by virtue of the fact that we’ve progressed to this point, we’re now smarter, more enlightened and so better than all the moments before this. There’s a kind of arrogance that seems endemic to the fact that we’re here now – the most evolved and educated class of human beings history has known.

But a few moments from now, the people living then will think the same thing about themselves and see us as unenlightened bores. And the modern mind will have moved on to the new so-called facts of what turns out to not be science but is in truth scientism.

When theology is hitched to “the modern mind” as liberals aimed to do, its eternal verities are traded in for the changing whims of what that is now, and now, then now. And we have to unhitch the adjective ‘eternal’ from those verities – because they simply aren’t true any longer.

Okay, end of the editorializing. Adopting the modern view that the universe was a vast harmonious machine, liberals aimed for Unity. They tried merging revelation with natural religion and Christianity with other religions by looking for common themes. Thus, the study of comparative religions was born as an academic pursuit. They aimed to lower the wall between those who were saved and the lost, between God and man.

Liberals regarded the traditional and orthodox belief in a transcendent God who exists in a realm above and beyond the natural as stalling their agenda to unify and harmonize. They blurred the lines between the natural and supernatural and equated the spiritual realm with human consciousness. The spiritual realm became little more than the intellectual and emotional activity of human beings. And God was defined as the universal life force that even now is creating the Universe. One liberal said it this way, “Some call it evolution; others call it God.”

Remember, theological liberals, aimed to harmonize science with faith. The newest darling on the scientific scene was Darwin and his emerging theory of everything – Evolution by Mutation and Natural Selection. Theological Liberalism had no problem accepting Darwin’s theory.

While the challenge of some of the assertions of science to orthodox Christianity was serious, they were secondary to the new views of history. Those views were adopted from the scientific method, which began a rigorous review of the assumptions that had framed classical or traditional history. If facts are based on evidence and repeatable observations, what were we to do with history, which by its very nature refers to the past? Historical criticism became the framework for a new generation of historians and academics. If a defendant is considered innocent until proven guilty in a court of law, events regarded by traditional history as certain were now suspect until proven true. Modern sensibilities were read back into and layered over persons and events of the past.

The application of these liberal principles of historical inquiry to the Bible was called “biblical criticism.” But don’t understand the term criticism here to be pejorative. Biblical criticism simply meant a study of Scripture in order to discover its real meaning. But Biblical criticism discarded the dogmatics of traditional inquiry in favor of a more rationalistic approach.

Biblical criticism flowed into two streams, lower and higher criticism. The low-critic dealt with the problem of the physical manuscripts and codices. Their goal was to find the earliest and most reliable texts of Scripture, as close as possible to the originals. The work of lower criticism helped produce the large number of New Testament manuscripts we have today and assisted translators in the work of producing modern Bible versions.

Higher criticism proved to be a very different matter. The high-critic wasn’t so much interested in the accuracy of the text. He was more concerned with the meaning of the text. To get at that meaning, he often read between the lines or went behind the text to the events assumed to have produced it. This meant discovering who wrote it, when, and why. Higher criticism held that we can only get at the meaning of a passage when we see it against its background. Higher critics then went to work, systematically dismantling traditional views regarding hundreds of passages. A beloved Psalm, attributed in the text itself to David, higher critics tell us wasn’t written by King D. All because it has a word scholars say wasn’t used for forty-two years after David. So, it must have been written by the Jews in exile.

The methods of Biblical higher criticism weren’t new. They’d been in use for a while on other ancient texts. But during the 19th century, they were applied to the Bible. And for many liberals, all it took was some scholar with a Ph.D. to say a traditional view of a passage was wrong, it was this other thing, for them to categorically throw over tradition in favor of the new view.

Higher criticism agreed generally that Moses didn’t write the Pentateuch as both Jews and Christians had universally agreed till then. Instead, they’d been penned by at least four authors. And passages that seemed to be prophetic of future events must have been written after the events they supposedly foretold because modern scientific sensibilities don’t allow for the supernatural. High-critics said the Gospel of John, wasn’t = John’s Gospel, that is.

Diverging from the discipline of Biblical Criticism was what’s known as the search for the “historical Jesus.” Liberals like the idea of Jesus, if not the actual Jesus presented in the Gospels. You know, the One Who made a whip and cleared the temple and called people white-washed tombs. A liberal reforming Jesus was someone they could get behind, but not the substitutionary-atoning Jesus of the Epistles because THAT Jesus meant a Holy God whose justice demands a sacrifice to discharge sins. And that was an archaic idea no longer acceptable to modern sensibilities. So, liberal critics assigned themselves the mission of saving Jesus from such barbaric and outdated modes of thinking. They assumed the early church and writers of the Gospels embellished Scripture to that end. It was their task to sift through the text and pull out what was legitimate and what was bogus.

Literally dozens of so-called “lives of Jesus” were written during the 19th century, each claiming it revealed the true, historical Jesus. While most contradicted each other, they nearly all agreed to disavow the miraculous was central to the genuine Jesus story. They were bound to this since “science” proved the impossibility of miracles.

Quick editorial comment – Let’s be clear, the scientific method can’t prove miracles are impossible. Miracles are by their very definition outside the realm of scientific investigation because repeatability is one of the required elements of the scientific method. Miracles, by the very definition, are a contravention of the laws that govern the material realm, and AREN’T typically repeatable. Miracles are unexpected!

In their quest to merge science and faith, liberal theologians allowed the so-called facts of their time to be the filter through which they re-worked the content of the Christian Faith. They said Jesus not only didn’t work miracles, He never claimed to be the Messiah, or that history would climax in His visible return to establish the kingdom of God.

The cumulative effect of all this was the doubt cast on the Bible as the inspired and infallible Word of God as the authority for faith and practice.

When higher critics were done, Liberals were free to sort through Scripture to pick and choose what they wished. They read the Bible through the filter of evolution and saw a progression from blood-thirsty deities requiring sacrifices, to the Jews who embraced the idea of a righteous God served by those who pursue justice, love mercy, and walk humbly. This progressive revelation of God reached its climax in Jesus, where God is portrayed as the loving Father of all Humanity.

So far, our review of Theological Liberalism has seemed bent toward a tearing down of traditionalism. That looks at just one side of the liberal coin. The other side was the concurrent movement known as Romanticism.

During the early 19th century, Romanticism was a movement that flowed mainly in the artistic and intellectual communities. It looked at life through feelings. The Industrial Age seemed to many to reduce man to a cog in a vast societal machine. Romanticism was an attempt to lift man out of the gears and set him down as a glorious creator and engineer. Man was evolution’s apex achievement and had every right, duty even, to exalt in his lofty place, as well as to aspire to even greater heights. Romanticism focused on the individual and his/her ambitions to attain their ultimate potential. This was the genesis of the Human Potential Movement.

So on one hand, liberals aimed for unity, but Romanticism exalted the individual. Liberalism broadened its agenda to unify the two by harmonizing them.

Theological liberalism saw itself as the force to do it. Biblical Criticism had rescued the historical Jesus from the muck and mire of traditional orthodoxy. Romanticism then wanted to plant the idea of Jesus in the hearts of all people so they could become all their potential made possible.

by Lance Ralston | Aug 7, 2016 | English |

The title of this episode is Push-Back

As we move to wind up this season of CS, we’ve entered into the modern era in our review of Church history and the emergence of Theological Liberalism. Some historians regard the French Revolution as a turning point in the social development of Europe and Western Civilization. The Revolution was in many ways, a result of the Enlightenment, and a harbinger of things to come in the Modern and Post-Modern Eras.

At the risk of being simplistic, for convenience sake, let’s set the history of Western Civilization into these eras of Church History.

First is the Roman Era, when Christianity was officially opposed and persecuted. That was followed by the Constantinian Era, when the Faith was at first tolerated, then institutionalized. With the Fall of the Roman Empire in the West, Europe entered the Middle Ages and the Church was led by Rome in the West, Constantinople in the East.

The Middle Ages ended with the Renaissance which swiftly split into two streams, the Reformation and the Enlightenment. While many Europeans broke from the hegemony of the Roman Church to launch Protestant movements, others went further and broke from religious faith altogether in an exaltation of reason. They purposefully stepped away from spirituality toward hard-boiled materialism.

This gave birth to the Modern Era, marked by an ongoing tension between Materialistic Rationalism and Philosophical Theism that birthed an entire rainbow of intellectual and faith options.

Carrying on this over-simplified review from where our CS episodes have been, the Modern Era then turned into the Post-Modern Era with a full-flowering and widespread academic acceptance of the radical skepticism birthed during the Enlightenment. The promises of the perfection of the human race through technology promised in the Modern Era were shattered by two World Wars and repeated cases of genocide in the 20th and 21st Cs. Post-Moderns traded in the bright Modernist expectation of an emerging Golden Age for a dystopian vision of technology-run-amuck, controlled by madmen and tyrants. In a classic post-modern proverb, the author George Orwell said, “If you want a vision of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever.”

In our last episode, we embarked on a foray into the roots of Theological Liberalism. The themes of the new era were found in the motto of the French Revolution: “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.”

Liberty was conceived as individual freedom in both the political and economic realms. Liberalism originally referred to this idea of personal liberty in regard to economics and politics. It’s come to mean something very different. Libertarian connects better with the original idea of liberalism than the modern term “liberalism.”

In the early 19th C, liberals promoted the political rights of the middle class. They advocated suffrage and middle-class influence through representative government. In economics, liberals agitated for a laissez faire marketplace where individual enterprise rather than class determined one’s wealth.

Equality, second term in the French Revolution’s trio, stood for individual rights regardless of legacy. If liberty was a predominantly middle-class virtue, equality appealed to rural peasants, the urban working class, and the universally disenfranchised. While the middle class and hold-over nobility advocated a laissez-faire economy, the working class began to agitate for equality through a rival philosophy called socialism. Workers inveighed for equality either through the long route of evolution within a democratic system or the shorter path of revolution via Marxism.

Fraternity, the third idea in the trinity, was the Enlightenment reaction against all the war and turmoil that marked European history till then; especially the trauma that had rocked the continent through endless political, economic, and religious struggle. Fraternity represented a sense of brotherhood that rolled across Europe in the 19th C. And while it held the promise of uniting people in the concept of the universal brotherhood of man under the universal Fatherhood of God, it quickly devolved into Nationalism that would only lead to even bloodier conflicts since they were now accompanied by modern weapons.

These social currents swirled around the Christian Faith during the first decades of the Age of Progress, but no one predicted the ruination they’d bring the Church of Rome, steeped as it was in an inviolable tradition. For over a thousand years she’d presided over feudal Europe. She enthroned dozens of monarchs and ensconced countless nobles. And like them, the Church gave little thought to the power of peasants and the growing middle class. In regards to social standing, in 18th C European society, noble birth and holy calling were everything. Intelligence or achievement meant little.

Things began to heat up in Europe when Enlightenment thinkers began to question the old order. In the 1760s, several places around the world began to feel the heat of political unrest. There’d always been Radicals who challenged the status quo. It usually ended badly for them; forced to drink hemlock or such. But in the mid and late 18th C, they became popular advocates for the middle-class and poor. Their demands were similar: The right to participate in politics, the right to vote, the right to greater freedom of expression.

The success of the American Revolution inspired European radicals. They regarded Americans as true heirs of Enlightenment ideals. They were passionate about equality; and desired peace, yet ready to fight for freedom. In gaining independence from the world’s most formidable power, Americans proved Enlightenment ideals worked.

Then, in the last decade of the 18th C, France executed its king, became a republic, formed a revolutionary regime, and crawled through a period of brutality into the Imperialism of Napoleon Bonaparte.

As we saw in an earlier episode, the Roman Catholic church was so much a part of the old order that revolutionaries often made it an object of their wrath. In the early 1790s, the French National Assembly sought to reform the Church along rationalist lines. But when it eliminated the Pope’s control and required an oath of loyalty on the clergy, it split the Church. The two camps faced off against each other in every village. Between thirty and 40,000 priests were forced into hiding or exile. Atheists recognized the cultural wind was now at their back and pressed for more. Why stop at reforming the Church when you could pry its grip from all society? Radicals moved to remove all traces of Christianity’s influence. They adopted a new calendar and elevated the cult of “Reason.” Some churches were converted to “Temples of Reason.”

But by 1794 this farce had spent itself. The following year a statute was passed affirming the free exercise of religion, and loyal Catholics who’d kept a low profile during the Revolution returned. But Rome never forgot. For now, Liberty meant the worship of the goddess of Reason.

When Napoleon took control, he struck an agreement with the pope; the Concordat of 1801. It restored Roman Catholicism as the quasi-official religion of France. But the Church had lost much of its prestige and power. Europe would never again be a society held together by an alliance of altar and throne. On the other side of things, Rome never welcomed the liberalism reshaping much of Europe’s courts.

As Bruce Shelley aptly remarks, Jesus and the apostles spent little time talking about political freedom, personal liberty, or a person’s right to their opinions. Valuable and important as those things are, they simply do not come into view as values in the appeal of the Gospel. The freedom Christ offers comes through salvation, which places a necessary safeguard on liberty to keep it from becoming a dangerous license.

But during the 19th C, it became popular to think of liberty ITSELF as being free! Free of any and all restraint. Any restriction on freedom was met with a knee-jerk opposition. Everyone ought to be as free as possible. The question then became; just what does that mean. How far does “possible” go?

John Stuart Mill suggested this guideline, “The liberty of each, limited by the like liberty of all.” Liberty meant the right to your opinions, the freedom to express and act upon them, but not to the degree that in doing so, you impinge others’ ability to do so with theirs. Politically and civilly, this was best made possible by a constitutional government that guaranteed universal civil liberty, including the freedom to worship according to one’s choice.

Popes didn’t like that.

In the political and economic vacuum that followed Napoleon, several monarchs tried to re-establish the old systems of Europe. They were resisted by a new and empowered wave of liberals. The first of these liberal uprisings were quickly suppressed in Spain and Italy. But the liberals kept at it and in 1848, revolution temporarily triumphed in most European capitals.

Popes Leo XII, Pius VIII, and Gregory XVI by all accounts were good men. But they ignored the emerging modernity of 19th century Europe by clinging to a moribund past.

There are those who would say it’s not the duty of the Church to keep pace with changing times. The truths of God don’t change. So on the contrary, the Church is to remain resolute in holding to The Faith once and for all delivered to the saints. Faithfulness to the essentials of the Christian Faith is not what we’re referring to here. You can change the flooring in your house without agreeing with the world. Some Popes of the late 18th to mid 19th century seemed to kind of pull the blinds of Vatican windows, trying to keep out the philosophical ideas then sweeping the Continent. That posture toward the wider culture tended to only further alienate the intellectual community.

This early form of Liberalism wanted to address historic evils that have plagued humanity. But it refused to allow the Catholic Church a role in that work as it related to morality and public life. Liberals said politics ought to be independent of Christian ethics. Catholics had rights as private citizens, but their Faith wasn’t welcome in the public arena. This is part of the creeping secularism we talked about in the last episode.

One of the lingering symbols of papal ties to the Medieval world was the Papal States where the Pope was both spiritual leader and civil ruler. In the mid-19th C, a movement for Italian unity began that aimed to turn the entire peninsula into a single nation. Such a revolution wouldn’t tolerate the Papal States. Liberals welcomed Pope Pius IX, who seemed a reforming Pope who’d listen to their counsel. In 1848, he installed a new constitution for the Papal States granting moderate participation in government. This movement toward liberal ideals moved some to suggest the Pope as leader over a unified Italy. But when Pius’ appointed Prime Minister of the Papal States was assassinated by revolutionaries, Pius rescinded the new constitution. Instead of putting the revolution down, it broke out in Rome itself and Pius had to flee. With French assistance, he returned and returned the Papal states to an absolutist regime. Opposition grew under the leadership of King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia. In 1859 and 60 large sections of the Papal States were carved away by nationalists. Then in March of 1861, Victor Emmanuel was proclaimed King of Italy in Florence.

But the City of Rome was protected by a French garrison. When the Franco-Prussian War forced the withdrawal of French troops, Italian nationalists invaded. After a short engagement in September of 1870, Rome surrendered. After lasting for a millennium, the Papal States were no more.

Pius IX holed up in the Vatican. Then in June 1871, King Victor Emmanuel transferred his residence to Rome, ignoring the protests and threatened ex-communication by the pope. The new government offered Pius an annual salary together with the free and unhindered exercise of his religious roles. But the Pope rejected the offer and continued his protests. He forbade Italy’s Catholics to participate in political affairs. That just left the field open to more radicals. The result was a growing anticlerical course in Italian civil affairs. This condition became known as the “Roman Question.” It had no resolution until Benito Mussolini concluded the Lateran Treaty in February 1929. The treaty stipulated that the pope must renounce all claims to the Papal States, but received full sovereignty in the tiny Vatican State. This condition exists to this day.

1870 not only marks the end of the rule of the pope of civil affairs in Italy, it also saw the declaration of his supreme authority as the Bishop of Rome in a doctrine called “Papal Infallibility.” The First Vatican Council, which hammered out the doctrine, represented the culmination of a movement called “ultramontanism” meaning “across the mountains.” Originally referring to the Pope’s hegemony beyond the Alps into the rest of Europe, the term eventually came to mean over and beyond any mountain. Ultramontanism formalized the Pope’s right to lead the Church.

It came about thus . . .

Following the French Revolution (and here we are yet again, recognizing the importance of that revolution in European and world affairs) an especially strong sense of loyalty to the Pope developed there. After the nightmare of the guillotine and the cultural trauma of Napoleon’s reign, many Catholics came to regard the papacy as the only source of civil order and public morality. They believed only popes were capable of restoring sanity to society. Only the papacy had the power to guide the clergy to protect religion from political coercion.

Infallibility was suggested as a necessary prerequisite for an effective papacy. The Church had to become a monarchy adjudicating God’s will. Shelley says as sovereignty was to secular kings, infallibility would be to popes.

By the mid-19th C, this thinking attracted many Catholics. Popes encouraged it in every possible way. One publication said when the pope meditated, God was thinking in him. Hymns appeared that were addressed, not to God, but to Pius IX. Some even spoke of the Pope as the vice-God of humanity.

In December 1854, Pius IX declared as dogma The Immaculate Conception; a belief that had been traditional but not official; that Mary was conceived without original sin. The subject of the decision was nothing new. What was, however, was the way it was announced. This wasn’t dogma defined by a creed produced by a council. It was an ex-cathedra proclamation by the Pope. Ex Cathedra means “from the chair,” and defines an official doctrine issued by the teaching magisterium of the Holy Church.

Ten years after unilaterally announcing the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, Pius sent out an encyclical to all bishops of the Church. He attached a Syllabus of Errors, a compilation of eighty evils then in place in society. He declared war on socialism, rationalism, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, public schools, Bible societies, separation of church and state, and a host of other so-called errors of the Modern Era. He ended by denying that “the Roman pontiff ought to reach an agreement with progress, liberalism, and modern civilization.”

It was a hunker down and rally round an infallible pope mentality that aimed to enter a kind of spiritual hibernation, only emerging when Modernity had impaled itself on its own deadly horns and bled to death.

Pius saw the need for a new universal council to address the Church’s posture toward Modernity and its philosophical partner, Liberalism. He began planning for it in 1865 and called the First Vatican Council to convene at the end of 1869.

The question of the definition of papal infallibility was all the buzz. Catholics had little doubt that as the successor of Peter the Pope possessed special authority. The only question was how far that authority went. Could it be exercised independently from councils or the college of bishops?

After some discussion and politicking, 55 bishops who couldn’t agree to the doctrine as stated were given permission by the Pope to leave Rome, so as not to create dissension. The final vote was 533 for the doctrine of infallibility. Only 2 voted against it. The Council asserted 2 fundamentals: 1) The primacy of the pope and 2) His infallibility.

First, as the successor of Peter, vicar of Christ, and supreme head of the Church, the pope exercises full authority over the whole Church and over individual bishops. That authority extends to all matters of faith and morals as well as to discipline and church administration. Consequently, bishops owe the pope obedience.

Second, when the pope in his official capacity, that is ex cathedra, makes a final decision concerning the entire Church in a matter of faith and morals, that decision is infallible and immutable and does not require the consent of a Council.

The strategy of the ultramontanists, led by Pius IX, shaped the lives of Roman Catholics for generations. Surrounded by the hostile forces of modernity; liberalism and socialism, Rome withdrew behind the walls of an infallible papacy.

by Lance Ralston | Jul 31, 2016 | English |

The title of this episode of CS is Liberal.

The term “modern” as it relates to the story of history, has been treated differently by dozens of authors, historians, and sociologists. Generally speaking, Modernization is the process by which agricultural and rural traditions morph into an industrial, technological, and urban milieu that tends to be democratic, pluralistic, socialist, and/or individualistic.

In the minds of many, the process of modernization is evidence of the validity of evolution. The idea is that evolution not only applies to the increasing complexity and adaptation of biological life, it also applies sociologically to civilization and human systems. They too are evolving. So, progress is good; a sign of societal evolution.

But critics of modernization decry the abuses it often creates. Not all modern innovations are beneficial. The increased emphasis on individual rights can weaken a person’s sense of belonging to and identity in a family and community. It weakens loyalty to valuable traditions and customs. Modernization builds new weapons that may encourage their inventors to assume they’re superior, then use them to subjugate and dominate those they deem inferior, appropriating their land and resources.

Modernization is often linked to a creeping secularization, a turning away from theistic religion. Periodic revivals are viewed as just momentary blips in societal evolution; temporary distractions in progress toward the realization of the Enlightenment dream of a totally secular society.

It was during the 19th C that the rationalist ideas of the Enlightenment finally moved out of the halls of academia to settle in as the status quo for European society. Christians found themselves caught up in a world of mind-numbing change. Their cherished beliefs were assailed by hostile critics. Authors like Marx and Nietzsche attacked the Christian Faith from a base in Darwin’s popular new theory.

In an attempt to accommodate Faith and Reason, Ludwig Feuerbach, author of The Essence of Christianity, published in 1841, reduced the idea of God to that of a man. He said God is really just the projection of specific human qualities raised to the level of perfection.

In 1855, Ludwig Büchner suggested that science dispensed with the need for supernaturalism. A materialist, he was one of the first to say that the advent of modern science meant there was no longer a need to explain phenomena by appealing to the miraculous or some ethereal spiritual realm. No such realm existed, except in the minds of those who refused to accept what science proved. He said, “The power of spirits and gods dissolve in the hands of science.”

During the last half of the 19th C, Frederic Nietzsche made the case for atheism. Son of a Lutheran pastor, Nietzsche received an education in theology and philology at the Universities of Bonn and Leipzig.

An amateur musician, Nietzsche became friends with composer Richard Wagner, who like Nietzsche, admired the atheist Schopenhauer.

In Nietzsche’s philosophy, we see the fruit of something we looked at in an earlier episode. The rationalist emphasis on reason divorced from faith leads ultimately to irrationality because it claims omniscience. By saying there IS no realm but the material realm, it closes itself off to even the possibility of a non-material realm. Yet the process of reason leads inevitably and inexorably to the conclusion there MUST be a realm of being, a category of existence beyond, apart from the material realm of nature.

So Nietzsche embraced what has to be called non-rational ideas as the source for creativity, what he called “true living,” and art. An early indication his mind was fracturing, he identified as a follower of Dionysus, god of sexual debauchery and drunkenness. It’s no surprise he indicted Christianity as promoting all that which was weak. He hated its emphasis on humility and its acceptance of the role of guilt in aiming to better people by moving them to repentance and renouncing self. For Nietzsche, the self was the savior. He advocated for people to exalt themselves and unapologetically assert their quest for power. He coined the term Übermensch, the superman whose been utterly liberated from the outdated mores of Biblical Christianity and governed by nothing but truth and reason. This superman decides for himself what’s right or wrong.