During the early-mid 19th C, an interesting phenomenon spread over the thinking of parts of Western Europe and the US. It was a general negativity about the present, but a strong optimism about the future. In some places, it was almost giddy. The current political and economic situation might be a mess and the number of social ills piling higher. But the Enlightenment’s promise of a bright new day gripped the imagination of thousands. The recent boom in technological progress with things like steam engines, cotton gins, and spinning machines promised endless new products, markets, and employment. Medicine was making dramatic steps forward, promising less pain and longer life. Trains & steamships conquered distance in a way the generation before could not have imagined.

“Yeah, today might be tough; but hang on, because tomorrow is going to be awesome.”

While that mentality was spotty in Western Europe, it was pretty much a blanket across the United States. European immigrants remarked on the nearly euphoric positivity of their new homeland. This positivism was largely the product of the pervasive Evangelical Revivalism that owned most American churches and a good portion of the population. That Evangelicalism conveyed the idea that conversion to Faith in Christ conveyed a new heart that sought after holiness. People began to reason that that new heart ought to pursue holiness in a new world shaped by holiness. All this spilled into numerous reform efforts; attempts to remedy past grievances and address the growing number of new challenges industrialization had produced. For progress did not come cheap. As Charles Dicken’s wrote, “It was the best of times. It was the worst of times.”

So, Evangelicals went to work on reforming society.

Charles Finney championed abolition as being part & parcel of the Christian faith. He went so far as to refuse Communion to slave-holders.

Stephen Caldwell called for new tariffs to protect American wages and to fund the Christianizing of the public school system.

In 1816, the American Bible Society proposed distributing Bibles as a moral and spiritual antibiotic aimed to eradicate Theological Liberalism and any goofy ideas brought over by Immigrants.

The American Sunday School Union set up dozens of schools in urban centers to educate the growing pool of child laborers.

By 1858, Evangelicals in NYC had established 76 missions to minister to the needs of the urban poor.

While most reform-minded Evangelicals engaged the culture, a smaller group decided to pursue holiness by withdrawing from society to form separatist communes. Nathaniel Hawthorne labelled these religiously-motivated separatists “Come Outers.”

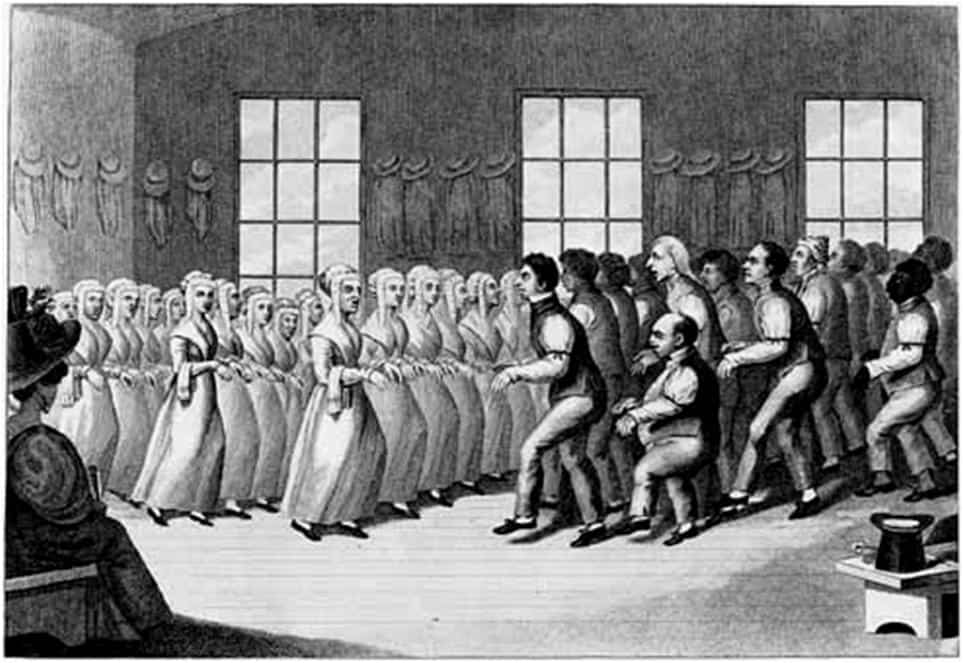

One example is a group known as the Shakers. Their original name was the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing. They began in the mid-18th C as a splinter group from the Quakers who at the time were moving away from their reputation as enthusiasts of ecstatic forms of worship. The Shakers didn’t just want to maintain that reputation; they wanted to ramp it up. So they became knowns as the Shaking Quakers. They were lead by the ardent and eloquent preaching of Jane Wardley who said the Millennium was about to begin with the Return of Christ. In preparation for the Return of Christ, they gave themselves to strict celibacy and a remarkable egalitarianism that saw a notable influence of women in the leadership of the group.

Shakers settled in colonial America but never saw many members until this era of reform in the mid-19th C when their community grew to its largest number, about 6000. The policy of celibacy as well as changes in society saw the eventual dwindling of the Shaker movement to just a single community today.

Another group of Come Outers were the Millerites.

William Miller was a well-off farmer and Baptist lay preacher in NE New York. He became convinced Christ would return sometime between 1843 & 44. His calculations convinced a large number of people across many churches and denominations. They set the date of March 21st, 1843 as the likely day Jesus would Return.

But Millerism, as it came to be known, was rejected by most clergy. By the beginning of 1843, the movement had hardened around enthusiasts and those who opposed it. Advocates of Millerism left their churches to form a new group of like-minded supporters. It hardened even more when after the evening of March 21st, Millerites donned special ascension robes and waited the big event. Some had gone so far as to give away their property. When the morning of the 22nd dawned, they were supremely bummed out. Because – and I don’t think I’m giving anything away here – Jesus in fact had NOT returned!

Miller did some quick figuring and said, he’d missed some minor calculations and needed to revise the date to April 18th. On April 19th, he re-upped by saying it wasn’t the days he’d gotten wrong, but the year. It would be March 21st, 1844; then Oct. 2nd. But by then the Millerites were a laughing stock and no new dates were set.

But instead of calling it quits and going back to their old denominations, the Millerites formed a new one – called the Adventists. In a bit of revisionism, they said that Christ really HAD come at the aforesaid & appointed time, but in Spirit, rather than in flesh. By 1863, the Adventists had 125 churches. They made themselves odious to many Americans by declaiming the US as the Great Whore of Babylon, doomed to the plagues of Revelation.

But the most extreme form of come-outerism was the 1830 emergence of the Mormons, under the leadership of Joseph Smith. Taking the name, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Smith claimed to have unearthed a record of a Pre-Colombian group of immigrants who’d had travelled all the way from the Middle East to settle in the New World. They fashioned an extensive civilization in the Americas but were wiped out by other Native Americans.

The Golden Plates Joseph Smith unearthed contained the record of that lost civilization, with a proper understanding of the Christian Faith. Smith claimed the Church as it was, was a horrible corruption – something God had never intended it become. Mormonism claimed to restore the Gospel Jesus and the Apostles taught.

But there was little connection between Joseph Smith’s vision of the Gospel and the Bible, so most churches and denominations opposed Smith’s emerging movement. They moved from New York to the Midwest. But when hostility broke out there, in 1847 they decided to make the big leap and head to a place all their own in the consummate come-outer move. They headed west and settled along the Great Salt Lake in what would one day be the State of Utah. They might as well have settled on the moon.

While each of these come-outer sects was radically different in its theological leanings, what united them was their short term pessimism about the world in which they lived. That’s how they justified their break with society. But they maintained a long term optimism about their ability, once they’d come out of a corrupt society, to found a healthy & holy community that could achieve it’s grand vision of establishing, if not heaven on Earth, then at least an outpost of it.

And each reprised a story that dates all the way back to the Desert Fathers we talked about early in Season 1. The hermits, who, having swallowed the dualism of Greek philosophy, fled the City to dwell alone in caves for years or sit atop a pillar for weeks. They understood holiness as physical separation from the world.

If that’s what Jesus had meant by being holy, that’s what He’d have done. It’s not. Jesus was to be found with people; often the kind of people least likely to show up at synagogue or church. Yes, Jesus spent time alone in the wilderness, but only in preparation for the City. He wasn’t a man OF the City, but He was IN it; where the love of God for needy souls could be seen and passed off to others. His strategy for reform wasn’t to withdraw FROM the world, it was to enter INTO it.

Secular reform movements copied religious come-outers in creating communes dedicated, not to a religiously-fueled spirituality, but a philosophically-based morality. Transcendentalists founded Brook Farm as an experiment in communal living. The Northampton Association organized an economic industrial cooperative. Oberlin, Ohio, was organized as a colony and college, with the college based on a philosophy of self-sufficient manual labor.

The American obsession with reform drew criticism from some. They saw it as the dark side of democracy. Brownson thought all the enthusiasm for reform was the logical consequence of Protestant individualism. Author Nathaniel Hawthorne who coined the term “come outers” said most reform was based on an overestimation of human nature.

Alexis de Tocqueville, by far the shrewdest observer of Americanism in the 19th C regarded the reform impulse as a mark of the health of American democracy.