In 431, the Council of Ephesus dismissed Nestorius’ explanation of the dual nature of Christ in favor of Cyril’s. But that Council was swayed more by circumstance and politics than by sound theology. While Nestorius’ Christology was mis-represented by his critics to be proposing, not just two natures to Jesus, but two persons, Cyril’s Christology put such heavy emphasis on Jesus’ deity, his Christology leaned toward monophysitism; that is, casting Jesus as having a single nature.

Now, to be clear, Cyril did not advocate monophysitism; that is, that Jesus had only one nature. He stayed orthodox, technically, by admitting Jesus was also human. But he said Jesus’ deity overwhelmed His humanity so that his humanity was like a drop of ink in the ocean of His deity.

The Council of Ephesus didn’t really provide a solid understanding on the nature of Christ. This was something the Church had wrestled with for 400 yrs. Church historian Justo Gonzalez ways, “Both sides were agreed the divine was immutable and eternal. The question then was, how can the immutable, eternal God be joined to a mutable, historical man?”

With Nestorius excommunicated & exiled, and Cyril’s Christology creating confusion, the scene was ripe for the emergence of even more confusion.

That came with the work of Eutyches, head of a monastery on the border of Constantinople. Though under Bishop Nestorius’ oversight, Eutyches disagreed sharply with him. He developed a view of the natures of Jesus that seemed a ready explanation that would bring both sides together. Eutyches emphasize the union of the two natures of Christ; a union so thorough it fused them into a new, third nature that was a hybrid of human & divine. This then is True Monophysitism, with a capital “M.” Eutyches agreed with Cyril Christ was only one person, but unlike Cyril, he said there was also only one nature.

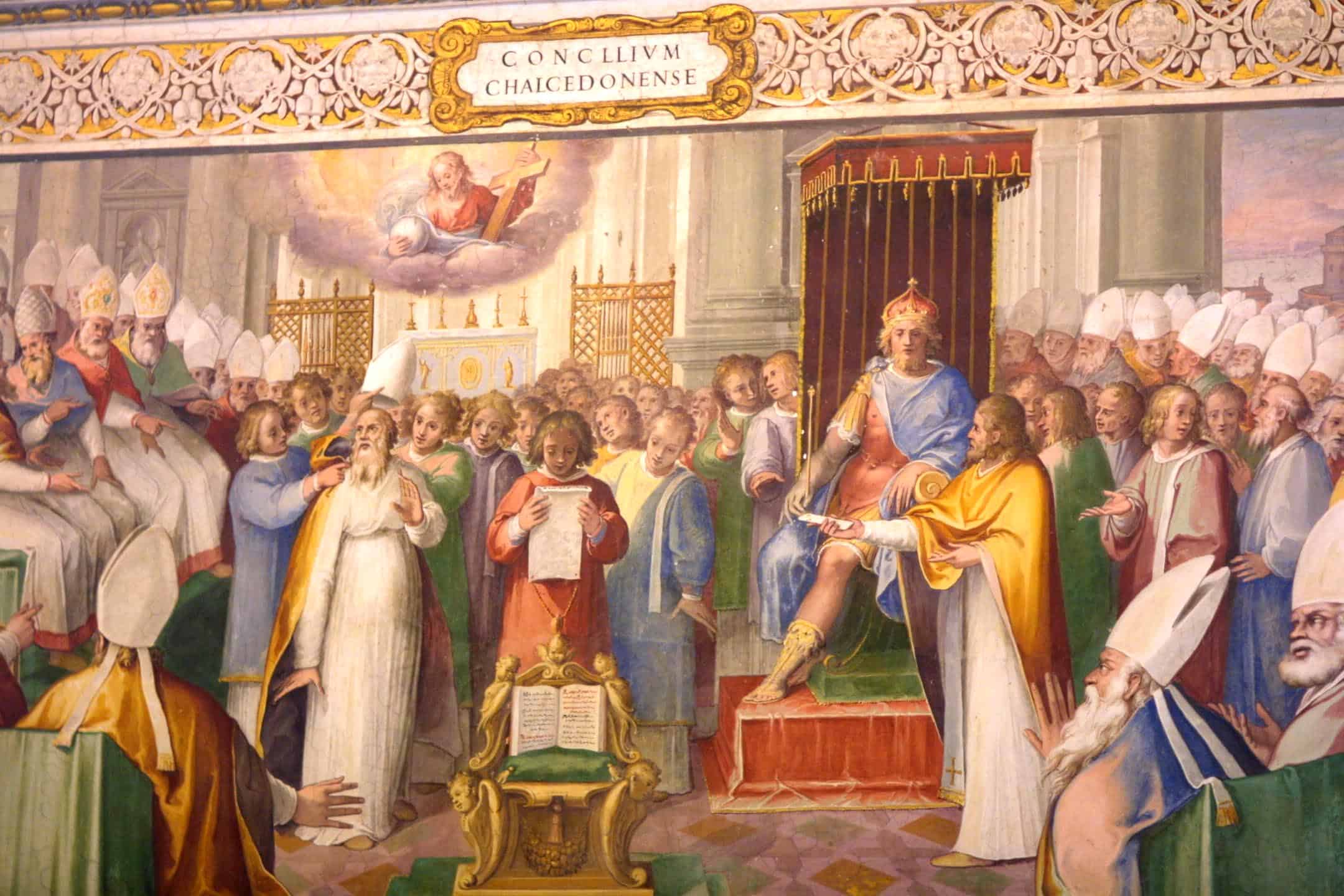

The Fourth Ecumenical Church Council at Chalcedon in 451 was called to deal with the Eutychian challenge.

But before we get to that Council, we need to talk a bit about an unfortunate event that happened a couple years before in 449 back in Ephesus, scene of the last Church Council in 431.

The 70-year-old Eutyches lead a monastery of some 300 monks just outside the walls of Constantinople for 30 years. When he began teaching that the two natures of Jesus as God & man were fused into a single new third nature, Constantinople’s Patriarch Flavian convened a council deposing Eutyches for heresy and excommunicated both him and those monks who supported him. Joining Flavian in this censure was Domnus, patriarch of Antioch, Alexandria’s age-old theological and political nemesis.

You can see where this is going, can’t you?

Sure enough, Dioscoros, Patriarch of Alexandria cast all this as an attempt on the part of the two bishops as an attempt top restore Nestorianism. So Dioscoros threw in his enthusiastic support of Eutyches and convinced Emperor Theodosius II to call a new council at Ephesus in 449 to deal with the matter. Though Pope Leo I’s predecessors had tended to side with Alexandria on previous matters, Pope Leo wrote to Flavian reinforcing the dual-nature view in a weighty theological work now known as The Tome of Leo. The pope also sent legates to the council, one of which would later become pope himself.

The Emperor authorized the Council to deal with the issue of whether or not Patriarch Flavian had justly deposed & excommunicated Eutyches for heresy. But, Flavian and 6 assisting bishops were not allowed to participate at the Council in Ephesus. Further stacking the Council against Flavian was that the Emperor made Flavian’s opponent Dioscorus president of the council. The papal legate was expelled from the proceedings at some point. It was clear that of the 198 bishops in attendance, most leaned toward Dioscoros.

In the first session, after a message from Theodosius II was read laying down the Council’s objectives, the remaining papal legates moved to read Pope Leo’s letter to Flavian as part of the official proceedings. But Dioscorus refused them, stating matters of dogma were not a matter for inquiry, since they’d already been resolved at the previous Council of Ephesus in 431. The issue for them to decide was whether Flavian had acted properly in deposing and excommunicating Eutyches.

Eutyches then was introduced. He declared he held to the Nicene Creed. He claimed to have been condemned by Flavian on a technicality & misunderstanding and asked the council to exonerate and reinstate him. The bishop that was supposed to present the evidence against Eutyches wasn’t allowed to speak. At this point the bulk of the bishops agreed that the record of the council condemning Eutyches ought to be read so they could get a better understanding of what evidence they’d used. When the record was read, some claimed it was inaccurate. Flavian’s action was cast as a personal vendetta against an innocent man. When Flavian attempted to speak, he was shouted down. But more than that. One report has Dioscoros and his supporters physically attacking him. The account is confused, so we’re not sure if it was bishops who went to brawling, some of the Imperial troops standing guard over the proceedings, or both. The upshot is, blows were given Flavian’s party. When the vote finally came in, he was deposed & excommunicated and died of his wounds a few days into his exile.

Eutyches & his brother monks were reinstated and the Council went on to deposed several more bishops who’d opposed Dioscoros. A deacon named Anatolius who was loyal to the Alexandrian bishop was now placed in charge of the Church of Constantinople.

When Pope Leo received a report of this council from his legates he condemned it, calling it the Latrocinium, a Robber Council and refused to recognize Anatolius as Bishop of Constantinople. Emperor Theodosius ignored Leo’s refusal, but all that changed when not long after he was killed in an accident and his sister Pulcheria came back to the Eastern throne. She married the general Marcian & together they cleared the teachings of Dioscoros and Eutyches from the Church. Patriarch Anatolius knew who buttered his bread, so he also quickly also condemned Eutyches’ monophysitism. Pulcheria & Marcian knew that the Second Council at Ephesus was a bad deal and that another, genuine ecumenical council was called for to deal with the issue of Christ’s nature once & for all. It was called in the city of Chalcedon in 451, directly across from Constantinople.

The council began on the 8th of Oct, with some 500 bishops, the largest council so far. Pope Leo sent a group of legates along with his Tome which had been ignored a couple years before.

The Council opened by reading over the Nicaean Creed, along with the letter from Cyril to Nestorius and the Tome of Leo. The bishops agreed all this was enough to resolve the issue before them; that is, articulating an orthodox position on the dual nature of Christ in one person. Emperor Marcian, most likely at the insistence of Pulcheria, directed the Council to develop a new creed that would not only unite the Antiochenes with their emphasis on Jesus’ humanity with the Alexandrians emphasizing His deity, but that would adequately express a Christology both East & West could agree on. A committee was appointed to develop a draft for discussion.

The first draft pleased most of the bishops; all except for the papal representatives. They felt the language was too close to Eutychian Monophysitism. They moved to replace the draft’s wording with that of Leo’s Tome, “two natures are united without change, and without division, and without confusion in Christ.” This change pleased all and was recognized as a better terminology than originally proposed.

The Council made clear what they’d produced wasn’t really a new creed, creed but an interpretation and elaboration of the work of the previous the councils and their work in refining the Nicaean Creed. It reads . . .

Therefore, following the holy Fathers, we all with one accord teach men to acknowledge one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, at once complete in Godhead and complete in manhood, truly God and truly man, consisting also of a reasonable soul and body; of one substance [and here they use the technical Greek word homoousios] with the Father as regards his Godhead, and at the same time of one substance with us as regards his manhood; like us in all respects, apart from sin; as regards his Godhead, begotten of the Father before all ages, but yet as regards his manhood begotten, for us men and for our salvation, of Mary the Virgin, the God-bearer [here they use the disputer phrase Theotokos]; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten, recognized in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation; the distinction of natures being in no way annulled by the union, but rather the characteristics of each nature being preserved and coming together to form one person and subsistence [hypostasis], not as parted or separated into two persons, but one and the same Son and Only-begotten God the Word, Lord Jesus Christ; even as the prophets from earliest times spoke of him, and our Lord Jesus Christ himself taught us, and the creed of the Fathers has handed down to us.

The Council maintained a clear distinction between the concept of a person and a nature. Jesus was said to have a both divine and human nature while still being only one person; he had everything he needed to be divine and everything he needed to be human. The Second Person of the Trinity didn’t just assume human person (the error of adoptionism); He took on a human nature. The Council also made an important technical distinction. The human nature of Christ did not exist as a person without the divine person of the Logos to assume it. This is called the anhypostasia/enhypostasia distinction, and may be simplified to this. Because of the power intrinsic to Himself as God, The Son could become man. But because of the limitations to himself as a mere man, Jesus could never become God. His divinity precedes His humanity. But because of the Incarnation, He remains human now in His glorified state.

We owe much in the way we speak of Jesus Christ today to The Council of Chalcedon. And as clear as its Christology is, the more you ponder the dual nature of Christ ion His one Person, the more the mystery of the Incarnation opens before you. We realize that the Chalcedonian Creed doesn’t so much explain or describe the nature of Chris as it does provide a set of rules for HOW we talk about Him. It’s more like the rules of grammar than literature. It sets boundaries and borders to work within, but leaves us to fill out what lies between them.

As we will see, Chalcedon didn’t answer all the questions that needed to be settled. A large part of the Eastern church concluded the Chalcedonian Dreed was too Nestorian and betrayed the simple idea of a single person Cyril fought for at Ephesus. Then, in Western churches, the question arose of how many wills Christ had, one or two. But all that was addressed with less drama because of the work of because of Chalcedon.

In the 16th C, the Reformers accepted Chalcedon as authoritative; it’s language incorporated in their own creeds and formulations. The in the 20th C, when liberalism challenged Christ’s Christ, Fundamentalists like BB Warfield appealed to Chalcedon as a faithful expression of what the Scripture says about the Son of God.

While all that was the main body of work done at the Council of Chalcedon, as with the other Councils, a number of other decisions were rendered to tighten up church business. These rulings are called canons. There are 30 of them from Chalcedon. For the most part their technical, house-keeping kind of things having to do with the behavior of the clergy. But Canon 28 of Chalcedon was to have far-reaching and monumental import. It reads . . .

The bishop of New Rome shall enjoy the same honor as the bishop of Old Rome, on account of the removal of the Empire. For this reason the metropolitans of Pontus, of Asia, and of Thrace, as well as the Barbarian bishops shall be ordained by the bishop of Constantinople.

The papal legates weren’t present when this Canon was passed and protested afterward. It was of course rejected by Pope Leo and became a major point of contention in later discussions.