This is the last of a dozen episodes on Rabban Sauma.

Having met with all the dignitaries his embassy on Arghun’s behalf required, Sauma was anxious to return home. The delay caused by the Roman Cardinals failure to appoint a new Pope had lengthened his stay beyond what he’d anticipated. Although no record of it is given, Arghun may have urged Sauma to return by a specific date. So he packed up and started the journey back to Persia. It was April 1288.

And remember, accompanying him was the French king Philip’s ambassador who bore a personal letter from the King to Arghun. The one Sauma carried was an official correspondence.

His route was the same as the one he took West. The only change was his trip to Veroli SW of Rome. The Cathedral of St. Andrew was an attraction he decided to include on his way home. It wasn’t much of a detour. What’s interesting about his stay in Veroli was his inclusion with several Roman church officials in the issuing of indulgences. These indulgences, usually issued in the Name of Christ, were rendered under the auspices of God the Father, indicating a nod on the part of the Catholics to The Rabban’s Nestorian emphasis. The Vatican museum has some of these indulgences granted by Sauma. They bear his seal showing a figure with a halo, left hand on chest and right holding a star. It bears the text, “Bar Sauma—Tartar—From the Orient” Tartar being the common word of Europeans for the Mongols.

After Veroli, Sauma took ship and arrived back in Persia in Sept; a journey of five months. He was immediately ushered into the Ilkhan’s presence. He handed off the various gifts and correspondences he’d been given to pass along to Arghun. He then gave his report, a full account of his time in the West.

Arghun was pleased that the kings of England and France were on board for an alliance against the Mamluks. Though the Pope hadn’t pledged to the alliance, he’d made clear his desire for closer relations. Stoked at that prospect, Arghun looked with great favor on the Rabban. He expressed his dismay at the hardships Sauma had endured on his journey and promised to take care of him for the rest of his life. He pledged to build the Rabban a church near the palace where he could retire to a life of quiet service of God. Sauma asked that Arghun send for his old friend Mar Yaballaha, head of the Nestorian Church, to come to court to receive the gifts and letters Western leaders had sent him. While there, he could consecrate the land for the new church. The summons was duly sent.

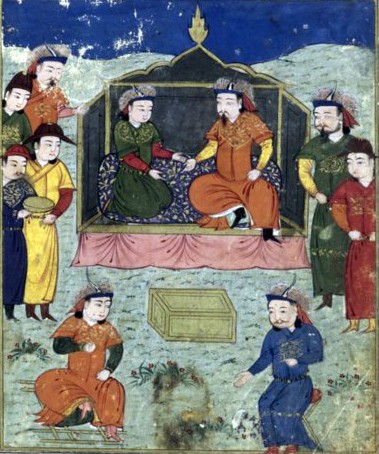

Arghun had a special tent-church constructed in anticipation of Mar Yaballaha’s arrival. When the Catholicos did, a three-day banquet was thrown with Arghun himself serving both Sauma and the Nestorian Patriarch. He commanded the people of his realm to offer regular prayers for the health of both the Rabban and Catholicos. The favor he showered on the Nestorians led to a greater boldness on their part across Persia. In 1289, Arghun appointed a Jewish physician as his vizier or prime minister and turned over a good part of the governance of the realm to his capable leadership. With both Christianity and Judaism on the rise, unease among Muslims began to roil.

Arghun remained hopeful of the alliance with the West against the Mamluks. He sent a letter by way of a Genoese merchant to Kings Edward & Philip, calling for them to make good on their promise of joining in a campaign to remove the Muslims from the Holy Land. He told them the Mongols would be attacking Damascus in January 1291. They were to attack the Mamluk headquarters in Egypt. They’d then meet in Jerusalem, where Arghun would help them conquer the City, and once secured, turn it over to Europeans control. Both Philip & Edward replied. While Philip’s letter is lost to us, Edward’s remains. He commended the Ilkhan for his zeal in wanting to rid the infidels from the Holy Land, but England wasn’t able to mount a Crusade apart from Papal blessing, which Edward encouraged Arghun to secure. But the Pope had made it clear; no such Crusade was in the offing. Gauging the political winds, Pope Nicholas sensed the monarchs of Europe were pretty much Crusaded out.

Arghun’s campaign against Damascus never materialized, and not because of the failure to gain western support. In the Spring of 1290, the Mongol Golden Horde to his north began a series of raids into Persian territory. When a rebellion broke out in the important city of Khurasan at his eastern border, it meant any movement West toward the Mamluks was out of the question. A half year later, he became gravely ill and died in March of 1291. Subsequent Ilkhans gave up attempts at an alliance with the West against the Mamluks. Though Ghazan converted to Islam, he attacked Syria and was able to hand the Mamluks a temporary defeat. Not able to hold the territory, when the Mongols retreated, the Mamluks returned. They were never able to defeat the Mamluks after that.

As for the Europeans, while Edward & Philip were up for a Crusade, the Pope wouldn’t sanction one. The monarchs might have pressed the issue had it not been for their issues at home. This was a time when Europe was fractured and disunited. Their inability to take advantage of the alliance Arghun offered meant the Mamluks were eventually able to conquer the last Outremer fortresses in Tripoli, then Acre.

When Arghun died, Sauma’s promised church next to the palace hadn’t been built. The new Ilkhan wasn’t interested in the project, but at Sauma’s urging, he provided funds and permission for a new church to be built in the Nestorian headquarters in Maragha, next to Mar Yaballaha’s house. It took three yrs to construct the elaborate structure, which became the home for the many artifacts and relics the Rabban had collected on his travels. Now in his mid and late 60’s, Sauma settled into the life he’d lived years before as a young man; one of quiet study and personal ministry to everyday followers of Christ. He reports that this was the happiest and most fulfilling time of his long and eventful life.

His health failing, Sauma was determined to see his good friend Marcos who’d become the Nestorian Patriarch under the name Mar Yaballaha, one last time. Though Marcos’ residence was in Maragha where Sauma’s church was, the headquarters of the Nestorian church was in Baghdad, so the Patriarch spent a good amount of his time there. Sauma made the journey there, the last of his many travels. After an emotional meeting between the two friends who’d shared such amazing adventures and accomplished so much, Sauma’s body, wracked by intense pain, finally gave out. In was January of 1294.

Mar Yaballaha was inconsolable. He wept profusely for three straight days. That was followed by a melancholy that took months to dissipate. Then the Nestorian Catholicos engaged in a series of correspondences with the Roman Popes, following up on the lines of communication forged by Sauma.

But the goodwill toward the Church launched from Arghun’s appreciation for Sauma’s embassy to the West, began to wither with the Ilkhan Ghasan’s conversion to Islam. When Mar Yaballaha died in 1317, Christianity was on the decline across Persia and Central Asia. It would never recover. The glory days of The Church of the East were now in the past, being covered by a thick dust of obscurity.

Sauma’s records were discovered among his papers following his death but were lost after being translated by a Syrian scribe some 20 yrs later. THAT account, as we’ve already suggested, was most likely highly abbreviate, focusing almost entirely on the religious aspects of Sauma’s adventures, specifically the many relics he viewed. The additional information in the Syrian translation comes off as little more than a setting of context for the religious narrative. Sauma’s diplomatic activities are presented as an afterthought. But, in light of Sauma’s ground-breaking and boundary-smashing embassy to the West, surely he took pains to document more than the finger and shin bones of dead saints.

The Syrian translator does include Sauma’s journals of the years he spent in Persia after his return from Europe. He even goes on to recount the persecution of Christians that took place after Sauma’s death when Ghazan became Ilkhan. The translator admitted, “it was not our intention to relate and set out in order all the unimportant things which Rabban Sauma did and saw, we have abridged very much of what he wrote, . . . and even the things which are mentioned here have been abridged, or amplified, according to necessity.” That necessity being the translator’s interest in the religious, rather than political, aspects of Sauma’s quest.

And that may account for why Rabban Sauma has been largely overlooked by popular history. His political impact wasn’t recognized, subsumed as it was under the editorial bias of his early chronicler. Excised as well from his report were his observations of life in Western Europe, what would have been a tremendous boon to historians researching this period.

In conclusion, while Rabban Sauma never returned to China and the court of Khubilai Khan to complete his adventure, he did accomplish most of what he’d set out to do. His original ambition, encouraged by his friendship with the young Marcos, was a religious pilgrimage to the headquarters of the Nestorian Church in Baghdad and the centers of Western Christianity. His dream of visiting Jerusalem birthplace of The Faith went unrealized because of the Mamluk domination of Palestine.

Sauma as a genuine scholar who did more than read books. He went to the places they wrote about. He was a gifted linguist, a skilled theologian, an effective diplomat. He must have been an imminently likable fellow who got along with everyone. All who met him embraced him quickly and sought to include him as an ally. His immense wisdom was repeatedly demonstrated in his skill at avoiding subjects sure to arouse the ire of his hosts.

Finally, let’s briefly recap his accomplishments.

He began as a scholar-monk in the storied Church of the East. His life of quiet study in a tiny house in the mountains of China was interrupted by a teenager named Marcos who’d made Bar Sauma his hero. They became inseparable friends. Marcos’ itch to visit the places he and Sauma read about eventually infected Sauma with the same hunger. They appeared before the Great Khan Khubilai, asking permission to head West on a heretofore unheard pilgrimage to the birthplaces of their Nestorian Church and the Christian Faith. Khubilai not only permitted them, he endorsed them as envoys of his court to his Mongol allies in Persia, the Ilkhans.

The journey West crossed some of the most inhospitable territories on the Planet. They encountered a mind-numbing plethora of different cultures, languages, customs & foods. When they arrived in Persia, the corrupt Patriarch of their church tried to turn them into political pawns. They adroitly side-stepped his shenanigans. Then, when he died, Sauma helped to have his friend Marcos elected as the new Patriarch, the Nestorian Catholicos known to history as Mar Yaballaha.

After several years in Persia, the Mongol Ilkhan consented to allow Sauma to continue his trek West to visit the centers of European Christianity. He charged him with an additional task; being his official envoy asking for Christian Europe to mount another of the Crusades they’d staged over the previous couple centuries, to clear the Middle East of the Muslim Mamluks. Sauma then embarked on his second great journey, from Persia to Constantinople where he met the Emperor and Eastern Patriarch, then on to Rome where he met the dozen Cardinals meeting to select a new Pope. When they were unable to, he headed to Paris where he met with King Philip, then to Bordeaux to meet the English King Edward. Securing promises of an alliance with the Persian Mongols against the Mamluks, Sauma headed back to Rome where he met with the newly installed Pope Nicholas IV and helped serve the Easter celebrations.

When the Pope proved evasive in pledging support for a new crusade, Sauma headed back to Persia where he was welcomed by a grateful Ilkhan.

Every student in Western schools learns of the famous Marco Polo. Almost any account of the Age of Discovery that helped lift the Medieval world out of its moribundosity lists the adventures and of Marco Polo as one of its premier causes. His chronicle, written down by a fellow prisoner, became a best-seller in Europe and helped whet the appetite of Europeans for the exotic riches of the Far East. Rabban Sauma, who lived at about the same time, has been overlooked in the popular telling of history. Yet his travels and accomplishments far surpass those of Polo.

If only that Syrian translator had translated ALL Sauma’s journals! If only . . .