This is Episode 9 in the on-going epic tale of Rabban Sauma.

Finally, Sauma has arrived in Europe. After two months aboard ship, his party arrives in Naples. Which is unusual because the trip from Constantinople ought to have taken less than a month. Here again, it’s Sauma’s account that seems to be lacking detail. Being a commercial vessel, most likely they’d used the route to further their business, so had put into port along the way for days at a time.

Sauma took some time in Naples to recover from the long voyage before setting out for Rome. While there, staying at a mansion provided by the ruling family of Anjou, Sauma witnessed from the roof, the Battle of the Counts on June 23rd in the Bay of Naples. This was part of the larger War of the Sicilian Vespers between the Houses of Aragon and Anjou. Sauma says the Anjou lost 12,000 men. What surprised him was the care given by both sides to avoid harming non-combatants. Familiar with the Mongol method of war, Sauma assumed no distinction between civilians and soldiers in battle. He was deeply impressed by the caution exercised in the fighting to avoid civilian casualties.

Naples had proven to be unsafe due to the conflict, so Sauma decided it was best to leave, even before having a chance to visit the city’s religious sites. An unusual move for him since that was his personal primary motivation. His unease may have been due to the sketchy political situation he sensed taking place around him. Better to ‘git’ while the ‘gitting’ was good.

So they packed up and headed for Rome.

The trip across Italy was yet another surprise for the Chinese monk. There was simply little landscape without some kind of settlement. Whether that was a solitary farm, hamlet, village, town, or city, the road led across a land that was, to Sauma’s thinking, filled with people. This was in sharp contrast with the territory he’d spent the previous decade in. It was possible to travel for days in Central Asia and not see another soul nor evidence of settlement. The path he now took went up and down hills, but after the towering peaks he’d traversed earlier in his pilgrimage, they were but bumps in the road.

As he approached Rome, he rehearsed his speech to the Pope, asking for him to call a Crusade of Europe’s’ monarch against the Muslim Mamluks that would coincide with a Mongol attack from the East. But word was carried to Sauma that Pope Honorius IV had died in early April. Instead of being disheartened, Sauma increased his pace, hoping to be among the first to speak to the new Pope.

But it was not to be. The twelve cardinals charged with the task of selecting the pope couldn’t reach a decision, largely because several of them wanted to wear Peter’s ring.

Arriving in the City, he sent word to the Cardinals of his presence, requesting an audience. Surprisingly, they invited him into that sacred place where the pope is chosen, the papal palace next to the Church of Santa Sabina. No one else was allowed into their deliberations but their closest assistant. So this was an uncommon honor. Even so, Sauma was briefed on proper etiquette when meeting the Cardinals. He made a good impression and proved a welcome distraction from the grinding machinations of the would-be popes. Their task proved so stressful, half of the Cardinals died before the end of that Summer.

After initial introductions and realizing how far the Rabban had traveled, the Cardinals expressed their dismay and concern for his health. They assumed it would take weeks for him to recover his strength and urged him to rest. He assured them his stay in Naples had been sufficient and that he had pressing, indeed, supremely urgent matters to share with the Pope. In this way, he hoped to impress on them the need to be quick to find Honorius’s replacement.

But they would not be hurried. They insisted he get more rest and pondered what his arrival and embassy might mean for the future of Europe and the Church. How might Sauma’s mission effect WHO they selected as the next Pope? Should they pick someone who’d be amenable to his request for an alliance with the Ilkhans, or someone who’d refuse?

They decided it was best to avoid political discussions with the Rabban altogether. A safer subject, and one of genuine interest to them, was Sauma’s faith. How was the Church of the East now different from the Roman church? The rift that had separated East and West occurred all the way back in the 5th C. It was over 800 yrs later. How had the two expressions of the Christian Faith diverged, they wondered. And how had Christianity reached all the way to the Far East so that a monk would embark on such a seemingly impossible pilgrimage as Sauma had?

In his account Sauma admits some frustration with the Cardinals’ refusal to let him pursue his political assignment. But when it was clear they would not entertain his embassy along those lines, he warmed to the task of explaining his beliefs and the history of the Nestorian Church.

Sauma explained that the headquarters of his church was in Baghdad and that he was the Patriarch of the Church of the East’s official representative to the court of the famous Khubilai Khan. The Cardinals were eager to hear how Christianity had reached China. Of chief concern to them was who’d brought them the Gospel. Sauma spoke of the Apostle Thomas who carried the message of Christ to Mesopotamia, Persia, and all the way to India. Thaddaeus and Mari also played a role in planting churches in the East. These were all names the Cardinals were familiar with and settled any concerns they had that the Nestorian Church rested on an apostolic foundation.

Sauma told them of the extensive missionary activity of the Nestorian Church. They’d planted churches among the Mongols, Turks, and Chinese. Their outreach to the children of the Mongol elite had proven especially effective. Then he brought the conversation back round to his embassy. Christianity was favored in the Mongol realm of Persia. In fact, the Ilkhan leader Arghun was a good friend and supporter of the Nestorian Catholicus Mar Yaballaha. Like the Europeans, Arghun wanted to dislodge the Mamluks from the Middle East. “Hey, how about an alliance?”

The Cardinals retreated to safe ground. They couldn’t agree to anything without a pope, they said. Besides, the previous Pope, Honorius IV, had already tried to rally support for a campaign against the Mamluks, but Europeans leaders weren’t interested.

So the Cardinals once more shifted the conversation back to theological issues. They wanted to know how closely the Nestorian Church aligned with Catholic doctrine. Sauma said no envoy from the Pope nor representative from the Vatican had come East with those doctrines. What the Nestorians believed was drawn from the apostles and fathers he’d mentioned earlier. The Cardinals asked him for a run-down of Nestorian theology.

This was a critical moment for Sauma. He needed to keep the door open with them. But he was aware of some differences between Nestorian & Catholic doctrine, especially in regard to the nature of Christ.

Consider for a moment how monumental the task was for Sauma. He has to explain the complexities of theology, specifically the intricacies of the Trinity, in Persian, which is then translated into Latin. The Cardinals listen, formulate questions for clarification, speak them in Latin which is translated into Persian and passed along to Sauma. For goodness sake! It’s difficult enough explaining the Trinity to someone in your own tongue.

Sauma’s managed to describe the Nestorian belief in the nature of Christ in such a way that the Cardinals took no offense. Next, they queried his beliefs about the Holy Spirit. He engaged them in a back and forth Socratic dialog that not only satisfied their concerns about his doctrine but greatly impressed them with his erudition.

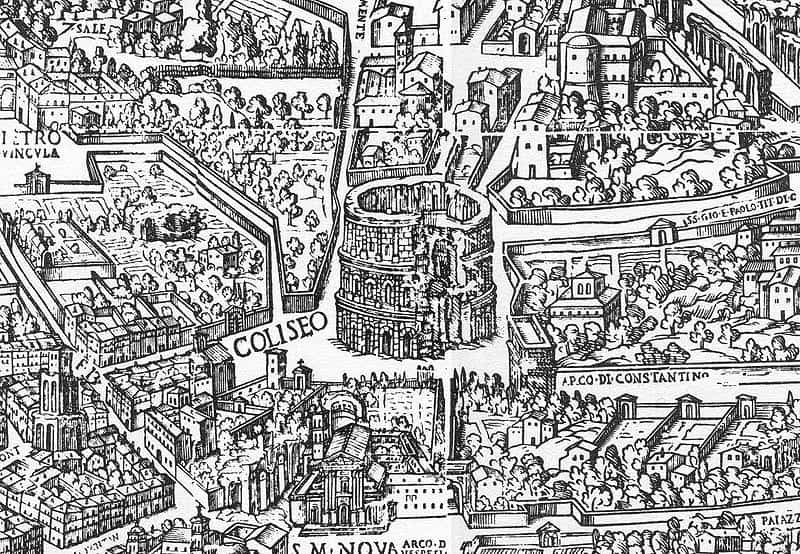

In fact, Rabban Sauma’s replies, included in his account of the meeting, did convey ideas the Cardinals would have found heretical. But it seems they wanted to avoid controversy as much as he did. Realizing further discussion with its parsing of details would only increase the chance of running afoul of their favor, Sauma indicated he thought his explanation of Nestorian theology was sufficient. He now realized the lack of a head for the Catholic church was a hindrance to his mission. He asked the Cardinals to appoint him someone who could take him round the religious sites to be seen in Rome. They assigned him several monks to escort him on a tour of the Eternal City’s churches and monasteries.

The first and most impressive site he was shown was the old Basilica of St. Peter in the Vatican. Of course, what he saw is not the St. Peter’s of today. That wasn’t built till the 16th & 17th Cs. Still, the church of his time was massively larger than anything he’d seen besides the Hagia Sophia. He wrote of it, “The extent of that temple and its splendors cannot be described.” He was shown the 180 columns erected by Constantine, the altar from which only the Pope served Mass, Peter’s Chair, and Peter’s tomb, in which a gold sarcophagus was placed inside a bronze coffin, topped by a solid gold cross weighing 150 pounds.

Sauma was especially impressed by a relic purported to bear the image of Christ. Another feature in the church he enthused over was a throne on which popes crowned emperors. He reports his guides told him the pope picked up the royal crown from the floor with their feet, transferred it to their hands then placed it on the ruler’s head. This showed the supremacy of the Church over State; that secular power was under religious authority.

Either Sauma’s misunderstood or was misinformed. That wasn’t the procedure. After being crowned, the Emperor knelt and kissed the Pope’s feet. But it was a ritual going out of practice by Sauma’s time. Hostility between popes and monarchs was already growing.

After seeing St. Peter’s Basilica, Sauma was shown several other sites, all of major significance to the faith in Rome. While the architecture and furnishings of these churches and shrines were remarkable, Sauma’s account gives little attention to that aspect of them. He was far more interested in the hundreds of relics he was shown. Body parts, clothing, instruments, items tied to the Biblical stories of the saints were his special fascination. It’s clear Sauma attached deep spiritual significance to these relics, giving them a special place as means of communicating grace to his soul.

Having had his fill of the religious dimensions of Rome, and realizing the absence of a pope was stalling his mission, he decided to carry out the next phase of his task, visiting the rulers of Western Europe. The subject of our next episode.